Spanning four decades as actor, director, and screenwriter, the smirking face of Ugo Tognazzi was a near-constant presence in Italian pop culture. Most associated with the “commedia all’italiana” films that reflected the hypocrisies of postwar society, Tognazzi’s famously deadpan interpretation of unwarranted male bravado, coupled with an inscrutable penchant for mischief, long obscured the true nature of this complicated figure.

Thanks to a new translation of Tognazzi’s suis generis memoir, however, English-speaking audiences now have the opportunity to explore the psyche of this central figure of Italian cinema, revealing a complicated man who felt more at ease in the kitchen than on screen, yet remains elusive even in death.

Starting out as an accountant in his native Cremona, it was the war that thrust the young northerner into acting, completing his military service by entertaining Navy officials in the theater.

Performance came naturally for Tognazzi, and by the early 1950s, he had made a household name for himself co-starring on Un, due, tre for Italy’s newly-formed public television network. Despite its popularity, the popular variety show would only run through 1959, when an audacious gag at the expense of the President of the Republic earned it the honor of being the first show to be canceled in Italian television history.

Though Tognazzi would transition predominantly to the silver screen by the end of the decade, including a turn in 1958 in Steno’s cultish sci-fi parody, Totò in the Moon, it was his performance as a blindly zealous Blackshirt in Luciano Salce’s 1961 film, The Fascist, that took his career to the next level.

Amidst the radical changes of the 1960s, Tognazzi became involved in more “serious” projects, appearing as a perverse alter-ego of his director, Marco Ferreri, in The Conjugal Bed, and The Ape Woman, starring alongside Vittorio Gassman in Dino Risi’s immensely popular satire, I mostri, and directing himself in three features.

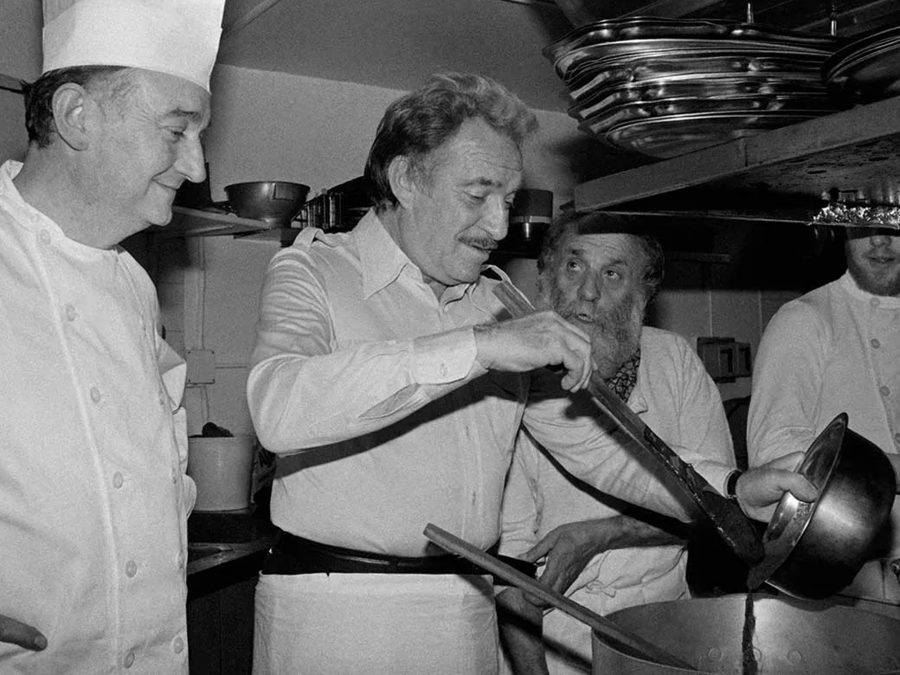

Yet however brightly shone his star, Tognazzi felt most at home in the kitchen. When he wasn’t acting in over 60 movies in that decade alone, Tognazzi was preparing pasta at his film premieres, dishing out recipes on Italian radio, and hosting infamously extravagant feasts for his famous friends, forcing them to rate his cooking by secret ballot.

These worlds would collide in 1973, when Ferreri cast Tognazzi as a wise-cracking chef in La grande abbuffata. Alongside real-life pals Marcello Mastroianni, Philippe Noiret, and Michel Piccoli, the plot finds the four eponymous characters moving to a crumbling Parisian villa to commit suicide through consumption, gorging themselves on haute cuisine.

In stark contrast to the oil crisis that plagued Italy that year and the austerity measures its government levied in response, Ferrari’s wry, visceral critique of unquenchable bourgeois greed struck a nerve with audiences. Despite their scorn, and that of Cannes Jury President Ingrid Bergman–who merely labeled it the most vulgar movie she’d ever seen–the film managed to take home the FIPRESCI Prize.

Riding the wave of La grande abbuffata’s popularity, Tognazzi would publish The Injester the following year. Known in Italian as L’abbuffone, itself a portmanteau of abbuffarsi (to gorge oneself) and buffone (clown) in an obvious wink to Ferreri’s film, it would be the actor’s most successful of several cookbooks to come.

Divided into three acts, The Injester is ostensibly more a call-to-arms than a compendium of recipes. From the jump, Tognazzi encourages the reader to join him in “[exhuming] the epicurean ideals that preached joy, life, and that made great the Roman world and the Renaissance.”

To be sure, a number of indulgent, borderline-bilious recipes, such as that of Cassoulet de Castelnaudary–counting seven different kinds of meat, from goose to pig’s feet–deliver on the sybaritic values he espouses. Mirroring his on-screen persona, however, Tognazzi can’t help but steep his pages in a playful, almost deviously ironic brew.

Opening his third chapter, a dish-by-dish review of La grande abbuffata, Tognazzi reflects on what he considers “certainly the most revolting feast of the film.” Set in a decadent dining room, lit like a chiaroscuro painting, the scene itself is defined by contrasts. With nude slides from a bygone era projected on the wall behind them, Tognazzi’s character challenges that of Mastroianni to an eating contest with nary a hint of conviviality.

The stars proceed to soberly slurp some 30 raw oysters apiece, and as sex commingles with death, beauty with decay, pleasure with disgust, past with present, high-brow with low, the curtain is raised on this grotesque journey from urbanity to abject bestiality, from desensitization to degradation.

Such a lack of restraint may well offend modern sensibilities, and rightfully so, particularly considering the glaring objectification of women as but another vice with which to gorge oneself. At best, Ferreri’s recurring denunciation of the unchecked lust of modern man trades in repulsion and self-disdain. For Tognazzi’s part, however, The Injester explicitly calls for a return to an “uninterrupted and secular flow of drool, sperm, and shit,” seemingly stripping the film of its irony.

Nevertheless, such work with Ferreri to his turn as a Chateaubriand-slinging butcher in Elio Petri’s scathingly anti-capitalist Property is No Longer a Theft, Tognazzi’s tendency to satirize and emasculate the avarice of man hints at a certain attempt to draw a line between pleasure and abject greed.

Even in The Ingester, Tognazzi contradicts his call for hedonism with a subtle politic of restraint, reflecting fondly on the utilitarian cuisine of his youth, manifested most memorably in the form of a simple soup stained black with the sweat and soot from a hard day’s work.

Tognazzi would spend the last decade of his life working steadily to cement his status as one of Italy’s most beloved actors, even earning himself a Best Actor Award at Cannes in 1981 for a rare dramatic turn in Bernardo Bertolucci’s Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man. Yet this period also found the actor retreating to his home on the Roman outskirts, spending his free time playing the role of family man from the comfort of his kitchen.

For all of Tognazzi’s complexity, the new edition provides no new essays or insights. Instead, a short, rueful “Postface” must suffice from its initial publication, where author and director Alberto Bevilacqua draws parallels between Tognazzi and the grotesque satirist François Rabelais, particularly in the actor’s use of a “sarcastic nostalgia” as a “spice to be sprinkled over a love for food.” The late Bevilacqua, who directed Tognazzi in two films, at once acknowledges and refutes Tognazzi’s self-sustained reputation as a skirt-chasing bon vivant, instead painting a picture more in line of a thoughtful man who would leverage humor in place of politics, someone for whom the spatula mattered far more than the spotlight.

The Injester, the English-language translation of Ugo Tognazzi’s L’abbuffone, will be published by Contra Mundum Press as part of their Agrodolce Series on November 19th.

Published 18 Nov 2022

This messy, invariably entertaining cinematic staple can represent anarchy, revenge and sexual release.

I’m Thinking of Ending Things is another sly critique of capitalism and the commodification of cinema.

By Anton Bitel

Juzo Itami’s ‘ramen western’ Tampopo – finally out on Blu-ray – is a culinary romp like no other.