Few directors have contributed as much to the canon of American muscle cinema as John McTiernan, the force of nature behind such masterworks as Die Hard and Predator. But no matter how great an artist’s track record is, there will invariably be the occasional dud. In McTiernan’s case, that is widely considered to be Rollerball, his ill-fated 2002 remake of Norman Jewison’s 1975 film of the same name.

Not only was Rollerball a critical non-starter and massive commercial flop, it’s also the film that sent McTiernan to prison: in 2013, he was incarcerated for lying to an FBI investigator about hiring a private detective to wiretap Rollerball producer Charles Roven, with whom he’d had disagreements about the film’s direction.

Rollerball has few staunch defenders and is hopelessly tied to the era in which it was made, but while it is easy to dismiss the film is not without merit. McTiernan may seem like a politically shallow filmmaker – even though there are undercurrents of nervousness about imperialism and globalisation in both Die Hard and Predator – but Rollerball deserves consideration as a sly polemic against capitalism, one that uses a fictional form of sports entertainment to stand up to oppressive economic systems.

Not that it meets the typical requirements for anti-capitalist filmmaking: it’s loud, with a non-stop nu-metal soundtrack and a brash visual style, and crassly commercial, with celebrity cameos from everyone from P!nk to Slipknot. The original screenplay allegedly retained more of the original’s sharp social commentary, which McTiernan dulled in favour of more Rollerball sequences. But by pushing political and social content to the margins, McTiernan actually makes a more effective directorial statement, not so much about the alleged evils of the sports entertainment industry or the prevalence of violence in media, but about capitalism itself.

Rollerball is set in a contemporary dystopia that is much closer to our own than that of the future-set 1975 film, a place where the legacies of crumbled regimes are still felt. The story follows Jonathan Cross (Chris Klein), the poster boy for Rollerball, a vicious team sport played in Central Asia and broadcast across the world. We never quite learn the rules of Rollerball – the film’s Greek chorus by way of sports broadcaster (played by WWE icon Paul Heyman) informs us that the “rules are very Russian and complicated” – but it’s clear that corporate sponsors dictate the game more than match officials, and Jonathan soon learns that blood drives up ratings better than anything else.

The league’s owner, Alexi Petrovich (Jean Reno), a former KGB agent with significant political sway throughout Central Asia, has set up certain players for violent downfalls in order to drive up viewership and fuel the gambling circuit. Thanks to Rollerball, so-called “Atlantic City syndrome” has taken hold of Eurasia, and a region already struggling to find its economic legs after the collapse of the Soviet Union is driven further into ruin.

The players of Rollerball are divided into classes: the headliners, who have devoted fan followings and live a pampered life, and the team players, many of whom are from Central Asia and “fight for peanuts.” Jonathan and the other Rollerball poster boys care little about the situation of the countries they compete in, which have been turned into playgrounds for their own pleasure; though Jonathan witnesses riots over worker’s rights, he’s content to speed down the empty freeways in his sport car. But for the ordinary team players, Rollerball is a job performed under threat, as Alexi has been known to “disappear” the families of rogue roller-skaters.

As a sign of their servitude, players have their team numbers tattooed on their faces, a mark that the more privileged Jonathan and Marcus (LL Cool J) forego. Alexi, an ex-communist who has taken nicely to the opportunities for exploitation afforded by capitalism, has pit the two groups against each other to distract from his own tyrannical reign, not just over the Rollerball circuit, but over a growing swath of territory and industry in the Eurasian region.

Throughout the film characters observe that they lack ownership over their own bodies. Marcus says that Jonathan is Alexi’s “boy” and compares their status to that of elephants in a circus. In a monologue just before the final showdown between Jonathan and his corrupt taskmasters, Alexi makes this same point: he has no need to hold political office or run businesses if he owns the men who do. Herein lies the film’s true message about capitalism: it is not the accumulation and production of goods that makes a capitalist powerful, but the commodification and ownership of bodies. If you control human beings, you control everything.

In the film’s final moments, we see the penny drop not only for the Rollerballers but the viewing public too, as both groups collectively rise up against their exploiters. For Jonathan, this means striking back against Alexi and his cronies. For those inspired by Jonathan, it means going out into the streets and building new systems and ways of being in the wake of old, oppressive ones.

Published 4 Mar 2017

By Taylor Burns

James Cameron’s original and best Terminator sequel has always existed on its own spectacular terms.

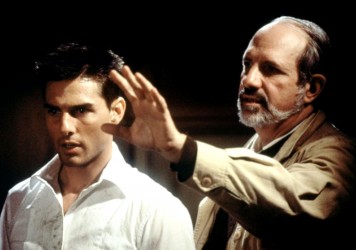

Twenty years ago Brian De Palma and Tom Cruise ushered in a new blockbuster era.

By Sophie Yapp

There’s never been a better time to revisit Danny DeVito’s cult comedy.