Location is everything. In 1948, William Keighley made the monochrome The Street with No Name, a film noir full of infiltration and imposture, and set it on the Skid Row of a fictional Center City (in fact Los Angeles). Seven years later, Samuel Fuller reworked this material with its original writer Harry Kleiner for a remake of sorts, House of Bamboo, but a decision to relocate events to postwar, post-Occupation Japan, and to shoot there too, would make all the difference, introducing a new geopolitical dimension to all the duplicitous plotting. Fuller also brought this noir out of the past into a new future by filming in CinemaScope and DeLuxe Colour.

The interplay between past and future is key to House of Bamboo. It opens in 1954 with a train robbery, against the backdrop of Mount Fuji. That train, transporting arms and artillery, is being guarded by both a Japanese policeman and a US Army Sergeant, in a nation that has recently regained its sovereignty and is now working closely with its former enemy and occupier. Yet the forward trajectory of this locomotive is stopped by a gang of ex-US soldiers turned criminals, who represent a violent and disruptive remnant of the past, and are so backward that they would rather kill their own wounded than risk having them taken alive. As the American Sergeant is shot dead in the heist, American forces are invited to join the local police investigation, and to help restore peace to the region.

Around this time, another ex-soldier and ex-con, Eddie Spanier (Robert Stack), arrives in Japan looking for his former comrade turned local gang member Webber (Biff Elliot), who recently died in captivity from injuries inflicted by his fellow gangsters. Eddie, with his flamboyant swagger (evidently the result of a war wound), his gruff laconicism and his readiness to action, is as hard-boiled as they come.

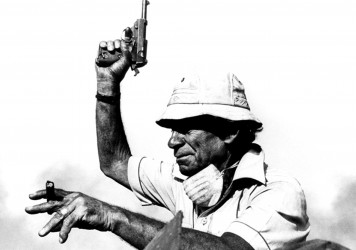

His fearless, single-handed attempts to shake down local pachinko parlours for protection money quickly attracts the attention of the gang’s leader, Sandy Dawson (Robert Ryan), who recognises in this delinquent soldier a man in his own image. Eddie shacks up with Webber’s widow Mariko (Shirley Yamaguchi), and is soon on his way to displacing the impetuous Griff (Cameron Mitchell) as Sandy’s ichiban or ‘number one’.

Eddie, however, is not really Eddie but an impostor, infiltrating the gang to bring it down, at great personal risk of getting killed at any point by either cops or robbers. This double agency makes great demands on Stack as an actor, requiring that he in effect play two characters, one cold and criminal, the other caring and just. It also allows him to embody the conflicts and contradictions of a nation still haunted by its violent past while working through a new dispensation of democracy and civilian life.

Cinematographer Joseph MacDonald’s wide lens frames the coexistence of Japan’s older traditions and emerging modernity, even as Eddie’s evolving relationship with Mariko tracks the same shift in American-Japanese relations that can be observed in the new friendly cooperation between local police and foreign military.

The climax at a rooftop amusement park sees the fugitive Sandy circling a model of the globe and taking deadly potshots, first at the police pursuing him, and then at random strangers. He is elevated, like a malevolent god, setting himself above and beyond earthly affairs. Yet he is also an arrested adult on a fun ride, reduced to the level of the actual children below – the inheritors of Japan’s future whose lives he is now endangering.

If Sandy embodies a world stuck in its own past and unable to move on, a world that feeds on itself and its own, then ‘Eddie’ protects and enables a different course – one of reconstruction and rapprochement. Fuller’s lean, taut thriller comes in a similar spirit, as one of the first American studio features to be shot in Japan, with the full cooperation of both the US military and the Japanese police. This is a much bigger, very different world from the small one that Sandy orbits, and his end brings an optimistic kind of closure to decades of aggression between Japan and America.

House of Bamboo is available on Blu-ray from Eureka! Video’s Masters of Cinema Series from 7 December.

Published 16 Dec 2020

By Adam Cook

Nagisa Oshima’s 1968 film Death by Hanging is now available courtesy of The Criterion Collection.

By Liam Dunn

From Shock Corridor to White Dog, the late director’s work has lost none of its social relevancy.

In 1972’s Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion, Meiko Kaji emerged as a bona fide, badass star.