In March 1945, as the Pacific War entered its endgame, the United States launched a concerted campaign to destroy Japan’s cities with fire. The stated aim was to cripple the country’s industrial base; in practice, civilians were indiscriminately attacked. Urban Japan, dense with wood and paper, proved highly vulnerable to incendiary bombs. By the war’s end on 15 August, almost all cities of appreciable size lay in ruins.

On 5 June, incendiaries fell on the eastern part of Kobe, the country’s main overseas port. In the ensuing chaos, fourteen-year-old Akiyuki Nosaka fled his burning home alone. Later that day, at a makeshift hospital, he found his sixteen-month-old adoptive sister and mother, who was severely burned; his father was never seen again. While their mother recovered, Nosaka and his sister drifted between refuges: first a relative’s home near Kobe, then a bomb shelter, and finally an acquaintance’s house in a different province. Malnutrition stalked them throughout, eventually taking the little girl’s life on 21 August.

Nosaka survived to become one of postwar Japan’s most original writers, but the traumas of these months lived on with him, resurfacing time and again in his work. He revisited this period in his best-known story, the novella Grave of the Fireflies (1967).

Once the US Air Force had disabled Japan’s major metropolises, it set its sights on smaller cities. On 29 June, the campaign reached Okayama, 70 miles west of Kobe. Awoken by the bombs, nine-year-old Isao Takahata found his home empty but for his older sister. Their father had dashed to the school where he was headmaster – protocol required him to protect the ceremonial photograph of the emperor. The rest of the family was in the backyard shelter.

Unaware of this, the pair panicked and fled into the blazing city. When his sister was injured by a blast, Takahata tended to her; she’d later say he had saved her life. They were reunited with their family after two days. Although relatively fortunate, Takahata would rank this experience as the worst of his life. Four decades later, by then a prominent director in Japan’s animation industry, he decided to turn Nosaka’s novella into a feature. He recalled those two days so vividly that details from them ended up in his film.

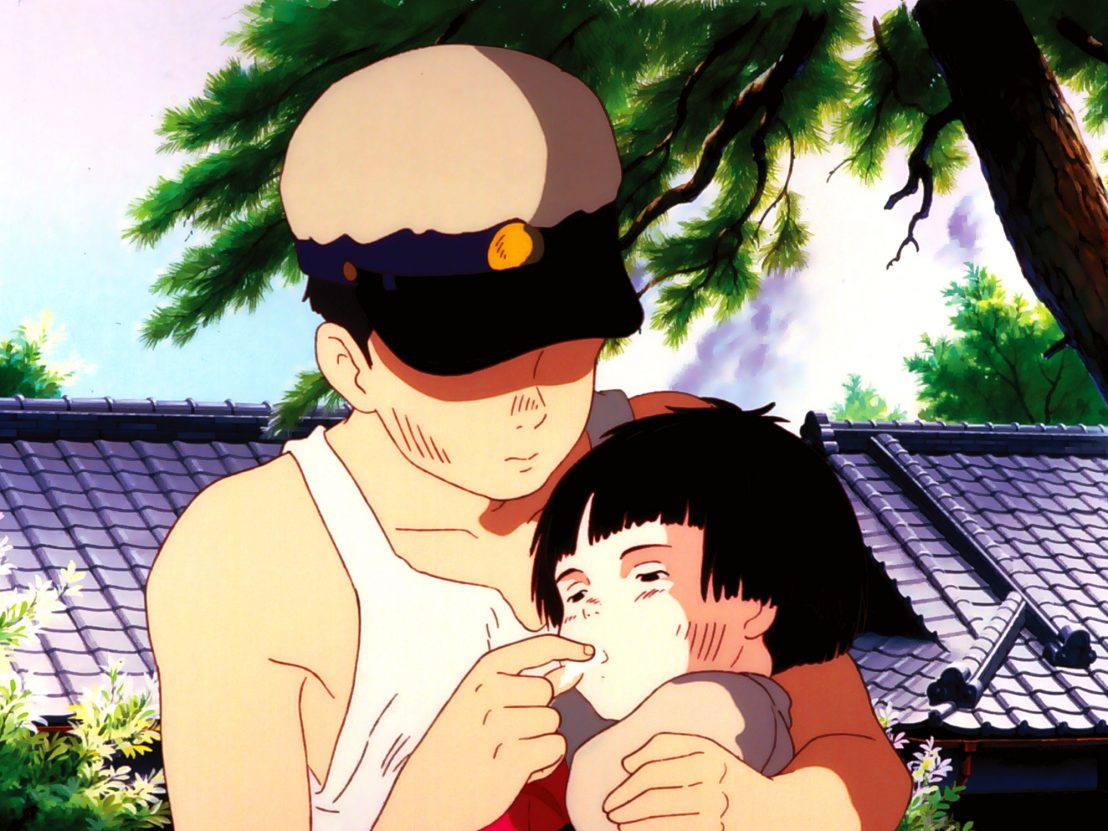

Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies (1988), then, is an unusually personal adaptation of a remarkably intimate text. The memories and philosophies of its two authors are entwined, sometimes inextricably, in its simple story. Nosaka was understandably protective of his novella, which he long suspected might be unfilmable. It took Takahata, a man who shared some of his formative experiences, to convince him otherwise. Here was a director with an exceptionally precise artistic vision, working in an environment – Studio Ghibli – geared toward realizing that vision, with a medium – animation – that resolved the problems of adaptation.

The story has the shape of a melodrama, and indeed the film is discussed above all in terms of its sadness. Most viewers experience it as a straightforward tragedy – a powerful evocation of war’s worst effects. Its American distributor described it as ‘a three-handkerchief movie on a scale of one to three’, and audience reactions bear this claim out: viewers young and old are often reduced to tears.

Reviews, Japanese and otherwise, tend to focus on the film’s capacity to move us. Relatively few ask what else it may be trying to do. Rarely is it substantially criticized, except when political sensitivities come into play. Commentary on the film can strike an almost reverential tone, as if its solemn subject and roots in autobiography place it beyond reproach. This consensus is a kind of vindication for Takahata, who was warned, when he set out to create a sombre historical drama with a realism almost unprecedented in animation, that nobody would want to watch such a film. Yet it also belies the nuances of his intentions and indicates that, in an important sense, Fireflies was a failure.

BFI Film Classics: Grave of the Fireflies is published by Bloomsbury on 6 May.

Published 6 May 2021

Isao Takahata’s unrealised passion project was intended as a follow-up to Grave of the Fireflies.

By Keno Katsuda

Like the original Godzilla, Anno Hideaki and Higuchi Shinji’s 2016 kaiju marked a turning point in Japan’s understanding of nuclear power.

The first and only film from Miyazaki protégé Yoshifumi Kondo stands among the studio’s best works.