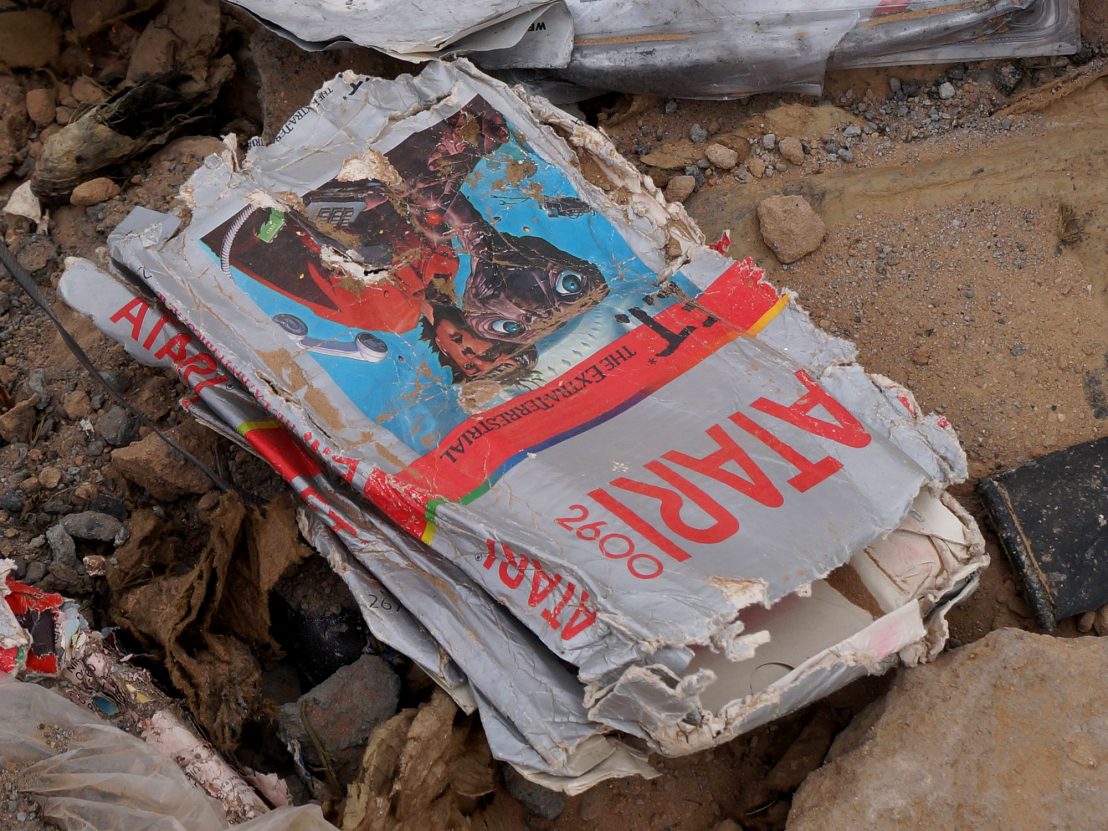

September, 2012: The rumoured remains of King Richard III are found buried beneath a car park in Leicester. Eighteen months later, half the world away in Alamogordo, New Mexico, an altogether geekier group of experts and enthusiasts make a similarly historic discovery in a 30-year-old landfill: a mass grave teeming with video game cartridges reportedly entombed in 1983, a fateful year for both the gaming industry and its pioneering company, Atari.

The video game industry may still be in its infancy when compared with cinema, television, music and literature, but it has already contributed its fair share of cultural history, and gaming folklore has no larger legend than that surrounding the mythically-proportioned Video Game Crash. The numbers speak for themselves: what was a $3 billion business at its peak in the early ’80s shrunk by 97 per cent to a mere $100 million within a handful of years. Atari, the industry leader with an astonishing 80 per cent market share (According to Forbes the combined share of Nintendo, Microsoft and Sony’s consoles only make up 63 per cent of today’s industry), bore the brunt of the collapse, posting $500 million losses in 1982 and laying off 80 per cent of its staff soon after.

Spoiler alert: the video game industry eventually bounced back. But in the ensuing years, a tidy narrative developed, complete with its own scapegoat. Step forward E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, an ill-fated tie-in game for Steven Spielberg’s hit family flick designed by Atari wunderkind Howard Scott Warshaw. Atari paid through the nose for the licence and set Warshaw, fresh from designing a popular and acclaimed adaptation of Raiders of the Lost Ark, the task of completing the project not in the usual timeframe of months, but weeks. An unprecedented five of them, in fact, to ensure a Christmas 1982 release. The result was by most accounts a fully-functioning, but disappointing and punishingly difficult game. Atari hoped to sell four million copies, but many remained on store shelves. And a significant chunk of that stock, so the legend goes, was buried in Alamogordo.

Imagine if infamous box office bombs like Heaven’s Gate or Cutthroat Island didn’t just sink film movements or production companies, but scuppered the entire movie business. That’s the reputation thrust upon E.T., and even a casual Google of the phrase ‘worst video game ever’ brings up legions of listicles perpetuating the myth. Noted internet grouch Seanbaby, for example, places E.T. in the top spot of his ‘Crapstravaganza’ feature, drawing a comparison to notoriously un-PC Atari game Custer’s Revenge (which ranked #9) in his entry: “The Atari 2600 had a game where General Custer raped Indians tied to cactuses, and that couldn’t kill the system… Calling [E.T.] a piece of trash is actually scientifically accurate.”

But how does it all stand up to cold, hard, disinterred fact? Like the case of the king in the car park, the excavation of this ancient video game burial ground was spearheaded and chronicled by a film crew, and was eventually cut together into a brisk, endearing documentary titled Atari: Game Over (initially launched, curiously, on Microsoft’s Xbox Live media platform, now more widely available on VoD). Director Zak Penn, elsewhere known for co-writing screenplays for Last Action Hero, Inspector Gadget and X-Men: The Last Stand, was one of the kids who experienced the crash first-hand.

“It was mystifying,” he recalls. “Everybody loved these games, they were really popular. And then it stopped.” But he was attracted to the E.T. story much later, when the myth was in full flow, exaggerated and proliferated by a younger generation online: “The internet is a very good, crowdsourced storyteller. What drew me into this specific story was… how the hell did all these pieces come together?”

Across 66 wholly enlightening minutes, Atari: Game Over picks apart the accepted narrative of the crash and interviews developers (Atari founder Nolan Bushnell), historians and other notable game buffs (including Ready Player One author Ernest Cline and former journalist and current screenwriter Gary Whitta), leading up to grand unveiling of the dig’s findings. In the process, the film mounts a defence case in support of E.T. and, in particular, designer Howard Scott Warshaw, who tagged out of the industry after the crash to become a writer, filmmaker and, latterly, a psychotherapist.

Penn’s thesis, which is borne out by his chosen talking heads and, indeed, the burial site’s contents (nowhere near the reported amount of cartridges, and only a proportion of them were E.T.), is that Atari’s bubble was bound to burst anyway, thanks to market saturation and lack of innovation. “The real issue about what happened with Atari was a technological one,” Penn explains. “They thought they had the hula hoop, they didn’t realise they had cinema.” Years later, the likes of Nintendo, Sony and Microsoft would build a new video game industry based on regular hardware refreshes, but Atari erroneously believed that their 2600 console was a business unto itself. When it failed, both Atari and the gaming community needed an easy explanation, and E.T. was it. Penn puts it in suitably Hollywood terms: “E.T. was the fall guy.”

E.T. designer Howard Scott Warshaw describes the Video Game Crash as the community’s first shared tragedy, akin to the Great Depression, and his game just provided the face. But when asked about the enduring legend around the game, he pinpoints a mode of social behaviour specific to contemporary online culture: “Being a hater is in vogue, particularly in this generation. It’s a social trend. I see it as a bunch of people exercising their wit, and I’m always in favour of that. But my game happened to be a lightning rod for haters.” That most of these critics placing E.T. at the top of their ‘worst game’ lists haven’t even played the game seems to be beside the point; its association with the downfall of the industry is enough to make it a worthy target.

What Atari: Game Over signals, though, is a different breed of video game discourse distinct from haters and myth-dealing nostalgia. Throughout, Penn and co exhibit a genuine curiosity to read against accepted wisdom, and there’s an infectious sincerity to the film’s approach to the game and its creator, best witnessed in the scenes documenting the excavation itself, which come across like a spiritual ceremony, or a communal happening. Enthusiasts gathered from all over the States, even abroad, to take part in the collective experience.

Warshaw himself was moved: “It was overwhelming to me to think that something that I did 32 years ago is still doing what I wanted it to do, which is to create some excitement and relief from boredom for a few moments. And there it was, right in front of me, before my very eyes, and I wept. Something that I found in this movie that I didn’t even know I needed as much as I did was redemption. It was a humbling moment.”

A reclaimed E.T. cartridge from the landfill now sits in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, complementing the copy of Warshaw’s earlier game, the critically-acclaimed space shooter Yars’ Revenge, which takes pride of place in the Architecture & Design collection at the Museum of Modern Art. But, reflecting on the dig, Warshaw is clear about which is the more prominent work: “if I would have come up with a brilliant game and everybody enjoyed playing the game, it would have been like Yars, and nobody would be there.”

By being hated, slated and entombed, E.T. was lifted out of its immediate context and cemented into pop culture history, suggesting, perhaps, that simply being good isn’t something worth phoning home about.

Published 3 Mar 2015

By Dan Einav

Apocalypse Now: The Game is coming to a console near you...

A new documentary reveals how three best friends created the ultimate Hollywood homage.

By Tom Bond

Roger Corman’s unreleased 1994 film The Fantastic Four was doomed from the start.