Robert Hartford-Davis was one of a number of British exploitation maestros who rose to prominence in the 1960s. Alongside the likes of Pete Walker and Michael Winner, Hartford-Davis could turn his hand to any touch-paper subject and churn out a slice of genre. In the late ’60s he made his horror debut with The Black Torment. Having previously cashed in on promises of titillating sexuality in films such as The Yellow Teddy Bears and Saturday Night Out, it was clear that Hartford-Davis’ real potential was in horror, and in 1968 his true pulp potential was realised with Corruption.

Scripted by Donald and Derek Ford, the latter a director of such salacious titles as The Wife Swappers and Suburban Housewives, Corruption was typical of the decade’s turn from the Gothic to the suburban. The film has an undeniably sleazy flavour, and owes a great deal to Hammer Studios’ occasional foray into psychological murder mysteries, simply with added grime. Most horror-infused murder flicks after it feel part of the same grimy universe; a mode that feels appropriate to name greasy-spoon horrors.

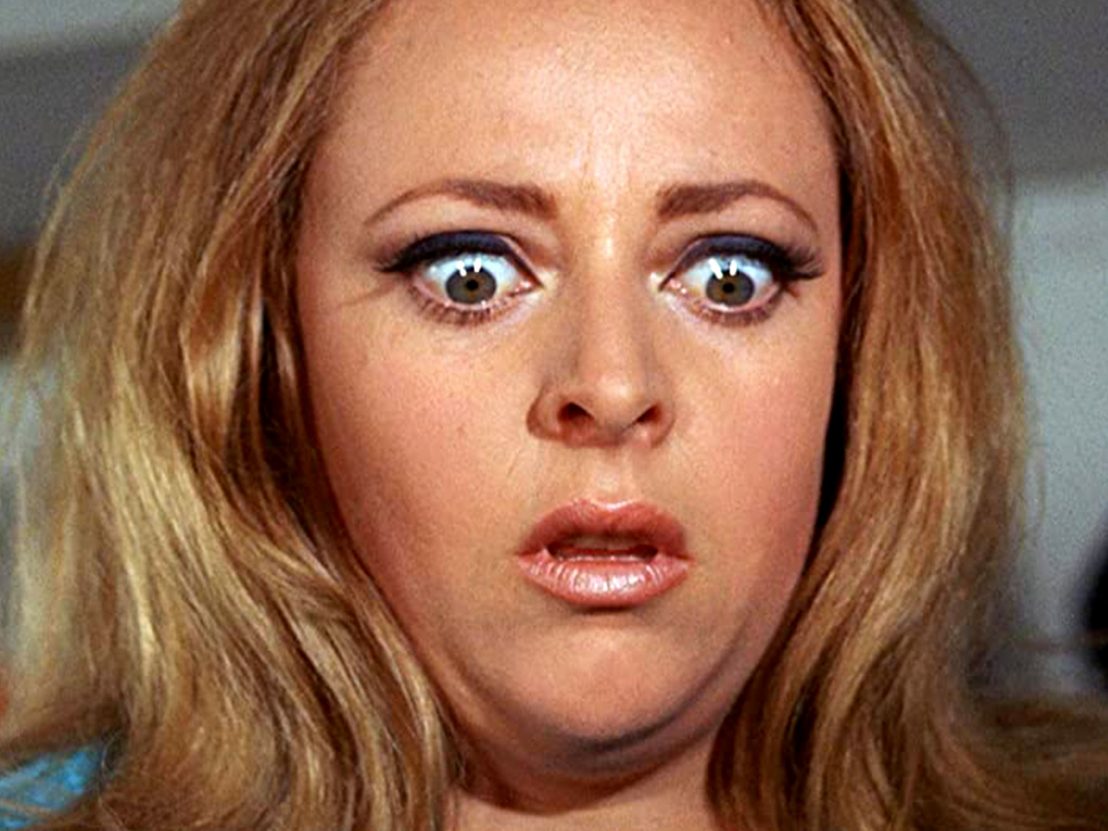

Corruption follows the increasingly unfortunate fate of medical doctor Sir John Rowan (Peter Cushing), who is in love with supermodel Lynn (Sue Lloyd). Attending a hip party held by a photographer called Mike (Anthony Booth), things get out of control as an impromptu photo shoot is held. Unhappy with this, Rowan tries to make Lynn leave, causing an accident in which a spot light falls on her face, effectively destroying her career.

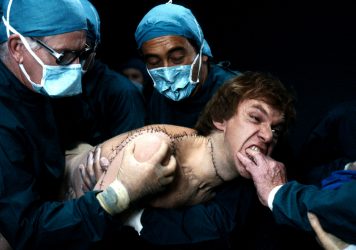

Using his skills as a surgeon, Rowan begins experimental treatment to repair Lynn’s scars. Stealing a pituitary gland from a corpse, he miraculously heals Lynn’s injuries. However, the healing isn’t permanent and soon requires fresh material. Desperation leads Rowan to become a murderer, decapitating women for their glands. Will his colleague Dr Harris (Noel Trevarthen) and Lynn’s sister Val (Kate O’Mara) be able to suppress their suspicions regarding Rowan’s behaviour as the murdered women hit the headlines?

This is, doubtless to say, an unusual film. In spite of its schlock horror, there are some interesting and timely elements that bleed into the celluloid from the era of the film’s production. Hartford-Davis’ film feels like a half-formed reminiscence, put together from aspects of other films, producing something of a late ’60s catalogue of British genre tropes.

Moving on from the decade’s earlier youth movements, in particular the beat movement that produced an equally hedonistic backdrop, British cinema of the mid-’60s went into swinging full colour. It may be surprising to view the first third or so of Corruption and find a film more akin to an over-the-top segment from Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up.

Just like Blowup, Hartford-Davis explored the narcissism of the age, metastasised to the growing media and fashion industries. Unlike Antonioni’s film, Corruption’s portrayal is garish, to the point of an entertaining parody. Whereas the parties of Blowup have a dark menace and melancholy, those of Corruption feel gleefully absurd. For those with a taste for the kitsch, Hartford-Davis’ capture (and, in some ways, misunderstanding) of what constituted ’60s cool is one of the film’s primary draws.

Another unusual period aspect comes in the score by Bill McGuffie, whose jazz inflections reflect perfectly the swinging aspects of the film but remain dynamically rigid, even as the narrative twists into horror. McGuffie’s previous score was for another Cushing vehicle, scoring a very different doctor in Gordon Flemyng’s Doctor Who film, Dalek Invasion Earth: 2150AD. Here he pulls melodies previously used for murderous Daleks for scenes of apparently tender reflections on a career hampered by misfortune. It makes for an increasingly odd cocktail.

Where Corruption really becomes more than just another proto-youth film is in its medical aspects. In what appears to be a loose lift from Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face, the film pivots to being about the fate of Lynn and the search by Rowan for a solution. Unlike Franju’s film, this is an entirely pulp enterprise. Whereas complex fatherly devotion drives Franju’s film, a sort of paranoid obsession drives Rowan. He is increasingly pressured by Lynn to carry out the crimes that become essential to maintain her appearance. The narcissism of the age leads to violence.

Of course, the medical narrative that underpins the film’s eventual horror is played remarkably straight in spite of its ridiculousness, mostly thanks to Cushing who possessed infinite skill in lifting uneven narratives. He’s never less than believable as a medical man, even when decapitating a woman on a train or preparing the space-age laser equipment supposedly required for surgery. Cushing is at the heart of the film’s appeal and, even if unaware of Corruption as a horror picture, his presence should alert the viewer of the inevitable switch in tone.

Throughout the decade British horror had several go-to themes. These were shared out between the Victorian Gothic and the modern day murder; a binary mostly set in stone by Hammer Studios’ output. Unlike the Gothic narratives, modern day horror and its psychological murder mysteries seemed increasingly porous to real life.

In the early ’60s, a noted series of murders swept across London. Over the course of several years, a number of sex workers were murdered around West London by a still-unknown killer dubbed ‘Jack the Stripper’ by the papers. The murders and their macabre particularity (removing teeth, no intercourse, suburban locations) had an undeniable effect on the grimy end of media, from the provocative tabloid headlines to crime and horror fiction.

The seedy atmosphere was already building in the years before, evoked most brilliantly by Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, a film that virtually destroyed Powell’s career by being honest as to the reality living just under the surface of post-war respectability. Beneath the bowler hats and closed doors, a wealth of nastier situations lurked.

Almost instantly, the case of what would be eventually named the Hammersmith Nude Murders seeped into the cultural subconscious, of which Hartford-Davis’ films were part of. The author Arthur La Bern turned the killings into his 1966 novel ‘Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square’, later adapted by Alfred Hitchcock as Frenzy. Television series started to incorporate sex maniacs and all manner of similar material with a sort of sly glee, often simply name-dropping the potential of such things. The case undoubtedly had a similar influence on modern day horror, increasingly focussing on troubled young men murdering their way across the capital.

By the ’70s, the greasy-spoon horror had arrived in full. Think of Roy Boulting’s Twisted Nerve, David Greene’s I Start Counting, Peter Collinson’s Fright and Straight on Till Morning, Pete Walker’s Frightmare and Schizo, or Freddie Francis’ The Psychopath and Craze. All of these films and many more feel like an echo back to the earlier atmosphere of the genuine crime spree and its unnerving ordinariness. Horror was no longer in the Victorian past but the blue-movie present. Killers replaced their capes and canes for dirty macs and even dirtier under-the-counter picture books.

Hartford-Davis would himself adapt the Hammersmith Nude Murders in The Fiend (aka Beware My Brethren), with Tony Beckley playing the murderer. Corruption’s latter half feels in some ways a dry a run for this killer-in-suburbia narrative; albeit Cushing starts his stalking in a Soho flat à la Peeping Tom, and concludes his grisly murder spree on the Lewes coast. All of the traits, however, are there: sweaty close-ups in wide-angle, brute force, kitsch surroundings. The killings in such films have a messy quality. The stylisation is far from that of slicker serial killer films. Messing of hair and the gleam of sweat is generally all that’s required.

Interestingly, such violence wasn’t enough for audiences abroad and Corruption is one of the few films where rumours of extra shots featuring greater gore and nudity for international distribution were true. It was hardly necessary considering how salacious the British cut still is. In spite of its violence, the most shocking thing in hindsight about Corruption was its poster campaign which alarmingly claimed that the film “is not a woman’s picture,” and went on to suggest that no lone women would be allowed into screenings. In reality, the film is more of a kitsch artefact, a genre mash-up of ’60s modes as opposed to a terrifying horror.

With its murders in bed-sits, heads in the fridge, and middle-class maniac rampaging around his holiday cottage, Corruption feels very much like the tipping point for the era’s exploitation and horror flicks. Its stain can be seen in many later horrors, in particular those of Pete Walker and Peter Collinson. Hartford-Davis bottled a particular nastiness, unintentionally showing a more unforgiving vision of a period so often cloaked in the veil of happy-go-lucky revolutionary zeal. This was not an era of shaggy peace and love or fab fashion frolics: it was as greasy as the groping hands that pawed you.

Corruption is available on limited edition Blu-ray via Powerhouse Films’ Indicator series on 30 August.

Published 30 Aug 2021

Lindsay Anderson’s spiky Thatcher-era comedy is the perfect sign off to his Mick Travis trilogy.

By Adam Scovell

The British acting icon spent his formative years the South London district, in a house built by his father.

By Adam Scovell

Visiting the scene of the director’s penultimate thriller, set in a bygone Covent Garden.