There are some films you watch when you need a warm hug from a familiar source. There’s no new terrain to explore, no outside world, no alarms and no surprises – they are simply soothing. Since a global pandemic was declared on 11 March, daily life has become so strange that the solace offered by comfort blanket movies is enhanced. In this series, we want to celebrate them, in whatever form they take.

There’s a tradition at weddings – if you haven’t seen it in real life, you’ve probably seen it in a film – where the newly married couple are introduced to a room full of their guests. It’s their first time entering the party as husband and wife, and music plays them in. At my own wedding, we helped choose the music carefully, and we had fun picking a song for this particular moment that might raise a knowing smile in a few of our guests. It was Tony Bennett’s ‘Rags to Riches’. The expansive, sweeping ballad with its soft croon always gives me a little electric jolt when I hear it. And I always hear it in concert with one line, one opening sequence, and one film: Goodfellas.

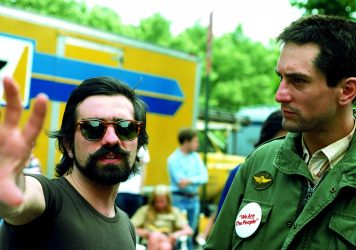

For the same reason as it seems like an odd choice of soundtrack for a wedding, it might seem strange to describe Martin Scorsese’s gangster classic as ‘comfort viewing’. The phrase entails something cosy, like a warm blanket. For my part, I like those sorts of films, too: Audrey Hepburn in swirls of designer chiffon in Funny Face, Gene Kelly musicals, Heath Ledger and his dimple in 10 Things I Hate About You. But comfort implies something unthreatening, right? Not a brutally violent, blackly comic story of a low-level mob associate turned police informer, which Scorsese took from the real story of mafioso Henry Hill.

From the very start of Goodfellas, the bravura camera work of the opening segment has every intention of hooking the viewer and keeping them wriggling on that hook. Scorsese bamboozles us with the glamour and vicarious thrill of the criminal lifestyle before sending Henry and his cohort on a steep downward trajectory. The restless, roving camera, the dollies, the freeze-frames, the deadpan voiceover, the faultless doo-wop soundtrack; in five minutes it’s pure sensory overload, visual storytelling on so enrapturing a level that any possible stray thought from the external world is pulverised.

On countless occasions, bad or good or just terminally bored, I’ve curled up on the sofa to see the pure, unravelling id of Joe Pesci’s Tommy and his murderous rages; Henry and Tommy bickering in the car as they comically forget to abscond from the scene of mob-sanctioned arson; that unforgettable camera tilt from the ground up, revealing Ray Liotta for the first time, leaning on the back of his car; or the moment where Karen (Lorraine Bracco) bleats, “I thought he was obnoxious.” And there she goes picking up the voiceover, unexpectedly and commandingly taking charge of the story.

I’ve always had a particular soft spot for Karen Hill, the ride-or-die gangster’s moll with lots of brains and a big mouth. Scorsese unequivocally presents Henry and Karen as a duo, working in tandem, and she is afforded a subjectivity that goes beyond the limited viewpoint of the men in this world. She explains to us exactly why and how she’s drawn to the mafia life, and how it excites her; she admits at one point that it “turns her on”.

She even tells us about her early misgivings trying to fit in with the other mob wives, and her fears about prison. “Don’t play the babe in the woods routine,” an FBI agent tells her later in the film. He’s right: she’s no innocent bystander. She’s not willing to let go of this life easily, whatever the costs. Her character – and the way Bracco plays her, full of energy and crackle – makes Goodfellas among the most insightful of its genre when it comes to women.

I find myself ever more drawn to the movie – and to the gangster genre in general – lately. There’s something undeniably comforting about them, in spite of their violence and ugliness. These are films which present a world that operates by strict codes; here the lines are clear. Everyone has their place in an admittedly crooked and morally corrupt hierarchy. We understand how these people operate, and on some level we probably wouldn’t like to admit, we can relate or project or identify with something in them.

Maybe not the part that has them stab someone to death in the trunk of a car. But in a looser sense: wouldn’t it be fun to behave so badly and be rewarded so fabulously for it? To be treated like you were special? To have the nerve to act so decisively in the face of betrayal or insult? It’s the same feeling of forbidden glee that audiences probably had when they first saw James Cagney fall with a thud to the floor at the end of 1931’s The Public Enemy.

I once knew someone who told me that he loved these films, films like The Public Enemy and Goodfellas and Blow, but that he never watched the endings, when the bad guys got their comeuppance. “They always get a happy ending if I turn the film off early,” he would say. But that’s not most of us. Most of us like the thrill of watching people live outsized lives, and the familiarity of knowing exactly where those outsized lives are headed.

There’s another thing that makes Goodfellas feel particularly comforting: familiarity. It’s up there with my most frequently-watched films, and it’s been a regular source of communal pleasure with people I know. Whether it’s my husband or my teenage sister, when we’ve watched the movie together it’s impossible not to elbow one another and pre-empt our favourite lines: “Fuck you, pay me,” and “It was outta RESPECT.”

Now that we’re under lockdown, my sister and I are separated for who-knows-how-long by a pandemic and a whole ocean. So not long after lockdown began, we decided to do a weekly Netflix Party viewing. The app allows you to view a film in real-time together, and to comment on it in a side-by-side chatbox. No surprise that Goodfellas was the first movie we chose, so we could type the quotes to each other in all-caps instead of yelling them at each other. To accompany it, we dreamt up our own version of mob wife outfits, draping ourselves in fur and gold jewellery and low-cut wrap dresses, uploading photos and commenting on them with deep-cut quotes like: “One night, Bobby Vinton sent us champagne!” It brought us together – let us feel a sense of occasion and community around moviegoing that we won’t actually have in person for a long time.

Together, we revelled in the little shared details and trivia from umpteenth viewings, like the beautiful bow on the back on Karen’s black cocktail dress during the Copacabana kitchen sequence, or the way Scorsese’s mama – playing Pesci’s mama in the movie – accidentally glances to camera and bursts out laughing while the guys around her ad-lib, or the nod to Crazy Joe starting a war that Marty would later follow through on in The Irishman.

At this point, Goodfellas isn’t just a comfort movie, but a whole private club that me and my loved ones can share. I think a lot of people (and there are a lot of us) who love Goodfellas feel the same. We get to be part of something – that reprehensible but oh-so-thrilling secret world of gangsters and guns and Lufthansa heists. We don’t mistake Henry or his friends for heroes, but the world’s got enough of those, anyway.

Published 30 May 2020

By Luís Azevedo

Is the American mobster movie destined to go the same way as the western?

A comprehensive guide to the directing credits of this great American auteur, from Mean Streets to The King of Comedy to Killers of the Flower Moon.

Charles Bramesco basks in the soothing whimsy of Sylvain Chomet’s animated marvel from 2003.