Like Do the Right Thing and Bamboozled before it, Spike Lee’s film is a wake up call to white America.

If “the history of the black man in America is the history of America,” as according to James Baldwin, then Spike Lee has spent decades as a historian, telling the story of the black man (and woman) in the US through both documentary and narrative film, complicating the notional boundary between the two in the process.

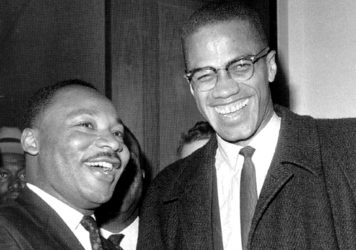

The majority of Lee’s films show a concern with the history of African-Americans and their position in American society, whether taking on monumental events of the past in the likes of Get on the Bus, 4 Little Girls, When the Levees Broke and Malcolm X, or representing the emotional response to real-world racism in Do the Right Thing, which, as well as being a whip-smart, vibrant, often hilarious portrait of a tight knit community, operates as a multi-faceted expression of frustration and anger at racial hatred and police brutality.

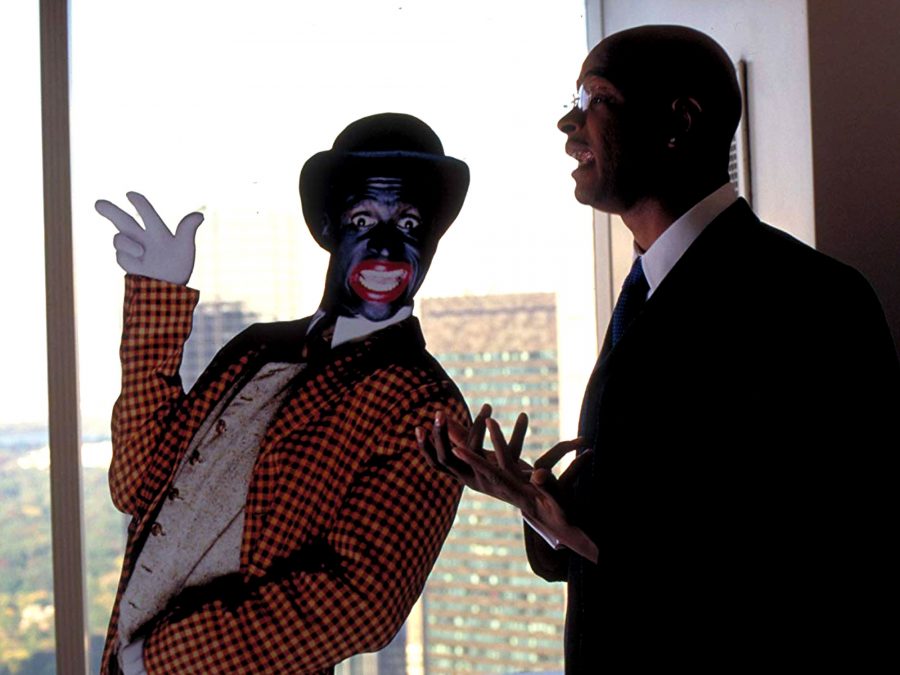

His latest feature, BlacKkKlansman, and his biting turn-of-the-century satire, Bamboozled, are both concerned with representations of blackness in television and film, past and present, keeping in constant dialogue with other works through the use of intercut archive images. The director also introduces footage of actual events into the mix, which appear as they would in a traditional documentary, with testimonial made by a character which is then supported by the presentation of this document as evidence. Each film blends and contrasts heightened fiction with extra-textual material and cultural documents in order to show the psychological and social state of both the characters in his work, and African-Americans in general.

Lee clashes his fictional world with our real one at multiple points in BlacKkKlansman. The film draws out the similarities between the Klan in the ’70s and the alt-right today, and the different ways we’re suckered into not regarding them as a threat – specifically through Topher Grace’s portrayal of white supremacist leader David Duke, who ditches the hood for the suit and tie in an attempt to mask his vile hatred. Bamboozled also aims to speak to its cultural context, but draws its line between the past and the present between the ongoing use of blackface, comparing it to how corporations have distilled and leveraged images of blackness for their own gain.

One standout moment in BlacKkKlansman sees Harry Belafonte tell a room full of Black Student Union members about the lynching of Jesse Washington. As Belafonte’s character recalls the details of this notorious race crime, Lee cuts between the room of students and a Klan screening of DW Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, once praised by President Woodrow Wilson (“Like writing history with lightning […] my only regret is that it is all so terribly true”) and now rightly condemned as a racist propaganda film partly responsible for the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, the villains of Lee’s period piece. Clips from The Birth of a Nation are intercut with photographs from Washington’s lynching, Lee offering a rebuttal to those who would hold up the film for its historical significance and ignore its debilitating effect on people.

As Pierre Delacroix (Damon Wayans), frustrated TV producer and chief protagonist of Bamboozled, lies debilitated at the film’s conclusion, he watches a clip reel of minstrel shows and other racist stereotypes of blackness cultivated by white people. It’s a moment that the film hints at earlier on, in a scene where a group of white writers comment on their favourite black characters. Lee jarringly cuts relevant clips from each quoted show into the scene. One white writer agonisingly stumbles through his description of ‘The Jeffersons’ as “my first experience of the black people of, uh, Africa”. Like Ron Stallworth (John David Washington), BlacKkKlansman’s undercover cop, Delacroix is the only black person in the room, bitter and resentful of the network and the monolithic images of African-Americans that it believes in and projects.

The frustration of being pigeonholed – of being made more sellable – explodes out in the film’s powerful end montage. As Ashley Clark observes in his book ‘Facing Blackness’, “Lee purposefully streaks the screen with unhealed psychic scars, and demands that the viewer join the dots between the past and the present.” BlacKkKlansman is a resurfacing of this specific method. This time, the film lulls its audience into a false sense of security, with an ending so uncannily tidy you could practically put a bow on it. But Lee destabilises this sense of accomplishment, his signature dolly shot transporting us from the main narrative to events witnessed from afar just one year ago in Charlottesville.

As Clark says of Bamboozled, “the montage would be powerful enough viewed in isolation”, but this is in addition to the rest of Bamboozled and BlacKkKlansman – both films being vivid displays of anger that take place in a heightened fictional world that is equal parts absurd, hilarious and horrifying. These final moments bring us crashing back down to earth with an understanding of how real the worlds of Lee’s films actually are. We are forced to connect the dots between past and present, fiction and reality – there’s no remove allowed, and any solace found in the triumphant narrative conclusion has long since dissipated.

In 1992, Lee opened Malcolm X with footage of the Rodney King beating – an appalling moment still fresh in the minds of viewers at the time of the film’s release – using it to recontextualise Malcolm X’s reasons for protest and resistance, reminding us that those reasons are just as valid as ever. It is nothing short of tragic that in 2018 Lee is still having to employ the same technique, as though his repeated calls to “wake up!” have fallen on deaf ears.

One hopes that 26 years from now, BlacKkKlansman might feel like a time capsule for when an overblown reality star was elected to the highest public office in government. Contemporary politics, however, isn’t offering much hope that this will come to be. Even looking back just on Lee’s career, the fact that the events of many of his films – whether it’s Radio Raheem’s murder in Do the Right Thing or white producers commodifying blackness in Bamboozled – ring true with such alarming familiarity is damning. At the very least, we’ve still got Lee to document and reflect this lunacy back at us.

Published 28 Aug 2018

BlacKkKlansman is the latest ‘Spike Lee Joint’ to feature a powerful, thought-provoking epilogue.

Find out by joining the author of ‘Facing Blackness’ for a special screening of the director’s 2000 film.

By Tom Bond

In BlacKkKlansman, the director dramatises real-life events in order to make his point.