Most accounts of Marcel Camus’ Black Orpheus include the anecdote of Vinicius de Moraes, the Brazilian poet who wrote the original story, walking out of the film in an outrage. Moraes claimed that Camus had merely made “an exotic film about Brazil,” but according to French historian Anais Flechet, Moraes later admitted that it was thanks to the film that the play was ever produced.

While he may not have shared the halcyon vision of the French director, and in spite of his apparent displeasure at the result, Moraes was instrumental, along with French producer Sacha Gordine, in developing Black Orpheus from his musical play ‘Orfeu da Conceição’. It was through his efforts in getting the adaptation off the ground that he attracted enough interest to put on a stage version. Even though it ran for just one month and suffered from a stalled start, the theatrical production brought together legendary musicians Antônio Carlos Jobim and Luiz Bonfá.

Praised for its black cast, mostly comprised of local actors, and lauded for Jobim and Bonfá’s soundtrack, the film won the Palme d’Or at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival and the Best Foreign Language Film award at the Oscars, Golden Globes and BAFTAs. All the world seemed to fall under the film’s spell.

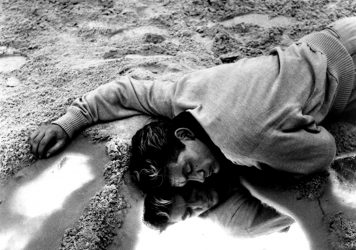

Like the play, Black Orpheus sets the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice in the slums of Rio de Janeiro during Carnaval. Breno Mello (a local soccer star) plays Orfeu, a tram driver who dances in the local samba school, while American-born French actress Marpessa Dawn plays Eurydice, a quiet girl who is visiting her cousin Serafina to escape a mysterious man who is pursuing her.

Loosely anchored to the classical myth, Camus’ film centres more on the lovers and their community and less on the mystical tragedy of death and the faithless hero. Set during the lead up to the big night of the Carnaval parade, the action bursts through a marble frieze of the fated lovers, sweeping the viewer up in a festival of colour and movement as the townsfolk dance and sing their way up the hill to the beat of the samba band.

In the distance, the concrete landscape of Rio de Janeiro competes with the brilliant blue of the ocean, while barefoot women carrying baskets on their heads inspect costumes for the parade, and children play with a stray dogs and fight over a football on the dusty slopes of Morro da Babilônia. All the while, the frenetic energy of the fading samba beat is slowly replaced by the laid-back rhythm of ‘A Felicidade’ – a picturesque scene of jovial harmony under the warm glow of the Brazilian sunshine.

It’s the perfect setting for a mythological tale. Or so it would seem. Camus discovered that setting a film in the favelas during Carnaval – even one firmly steeped in mythology – would inevitably take on a political dimension. At the time of filming, the Old Republic’s strict ban on samba music was still fresh in the public’s memory. Hailing from Africa, samba was seen as a dangerous expression of black slave culture, symbolic of unrest and protest. It was eventually legitimised as a community recreation with the formation of Samba Schools and is now considered a fundamental part not only of Carnaval but Brazilian identity. Even today, the performances at Carnaval are often used as a platform for social protest and awareness.

But it wasn’t the samba that the French director’s film became known for. Bossa nova – the fusion of samba and jazz – a style of music being played in Rio at the time, although even this new sound wasn’t immune from politics. The laid-back, low-key music that favoured gentle lyrical themes, belonged to the middle class and the arty crowds on the beach front – it was not the music of the slums. Having the Morro community sing bossa nova was thought by some to be inauthentic and insensitive to the true sound of the favelas. Nonetheless, it was the film’s soundtrack – rich with both samba and bossa nova styles – that bought this music to the world at large, influencing a generation of musicians.

To the French, Black Orpheus is considered Brazilian because it employs a mostly native cast and crew. But to the Brazil people, it’s European, as it was produced by French and Italian studios, and most of the royalties and profits went out of the country. Camus was neither part of the social realist movement of Brazilian Cinema Novo nor the French New Wave. He was a man apart, unaffiliated with any specific scene or political group. That’s not to say he turned a blind eye to domestic social issues – he understood perfectly well what life really looked like in the slums of Rio, he just chose to tell a different story.

In spite of what Moraes felt Black Orpheus should have been, Camus’ vision was never going to focus explicitly on the harshness of favela life. It is not a film about division or dissent. Instead, Black Orpheus pays homage to the power of myth, dance and song (personified in the mythological Orpheus), highlighting the cultural importance of these simple everyday pleasures. Camus wanted to celebrate the harmony and hope that can flourish even in the poorest places on earth, and it’s for this reason that the film continues to resonate today.

Published 21 Dec 2019

Louis Malle’s debut feature is a thrilling precursor to the French New Wave.

The French filmmaker’s haunting 1950 work fluidly blurs the line between technology and magic.

By Anna Cale

Sixty years on, Val Guest’s delightfully murky musical satire retains a defiantly British sensibility.