Dear Freddie,

Thank you. It’s rare to hear from people in the public eye who know how to articulate the twisted logic of bulimia. Like you said in Belfast when visiting the mother and brother of Laurence, who died aged 24 from a bulimia-induced heart attack: “When you talk about being sick and the compulsion to do it and the habit, I get it, because I’ve done it, and I still get the urge to do it now. But to try and convey it to somebody else is so difficult.”

We’ve internalised a damaging belief system that enables us to justify hurting ourselves. You externalising those beliefs with such honesty struck a primal chord in me. I have been behaviourally “recovered” for a decade, yet in some ways recovery is an ongoing process, never to be fully rubber-stamped.

I developed bulimia when I was 15, seven years younger than when you did, but without the scrutiny of the world media and minus the cricketing skills. This past week I was at my childhood home and found a bag of printed-out emails from that age. In one I confessed to a friend: “i throw up all the time, i don’t feel anything when i do it like you’re supposed to, like revulsion or anything, i just do it like it’s a job that has to be done and i do it, it’s been off and on for awhile… i like go a week when i am very controlled and then a week when it consumes me.”

The recipient was a smart boy but he couldn’t grasp it. No one could. One friend, all agitated, told me: “Eat chocolate cake and realise that you’re not fat.” Many friends and family members voiced their upset over my distressing habit of vomiting. I was touched and sorry, but it’s alienating to comfort someone who can’t comfort you, especially when you are sick with a mental illness.

That’s why what you and the Freddie Flintoff: Living with Bulimia team have done is marvellous and ground-breaking. It’s a way of putting this disorder on the map. You lay it bare by laying yourself bare. I can’t imagine the courage it took. I’m so grateful. You’re a pioneer, disabusing the dismissive and wrong idea that eating disorders only happen to silly teenage girls.

The stats you highlighted tell their own story: Over 1.5 million people in the UK suffer from eating disorders, approximately one in four are male; eating disorders cause more deaths than any other mental illnesses; 60 per cent of men with EDs don’t seek professional help; male athletes are 16 times more likely than other men to suffer with EDs; those who seek treatment for bulimia are nine times more likely to recover.

The first time I tried to seek treatment, my GP sent me away saying it was normal for girls my age to diet. I never forgave him. As you touch on in the doc, the reaction someone gets when they first ask for help can mean everything. Laurence’s doctor didn’t take him seriously. I do think the world has changed since that initial experience with my GP. The therapist I have now is a lifeline. (We’ve been Skyping during the pandemic.)

The three professionals you spoke to were all brilliant. I especially loved the sports dietician for pointing out that bulimia is a symptom of something else. “It’s never about food. It’s never about body image. It’s always about something deeper, this inability to like who you are, for whatever reason, deep down.” Nailed it, Renee McGregor!

It’s hard to get to the root cause when the symptoms are so distracting.

Doctor Omara Naseem told you that bulimia isn’t just throwing up, but all the obsessive behaviours that go into compensating for eating a large amount of food: exercising, restricting. Eating disorders present as the illusion of control, which is thrilling until they’re like “Psyche! We’re controlling YOU.”

You said it yourself. At your thinnest, when you were boxing, you were a shell of a person. There was no one behind your eyes to enjoy those abs. The idea that at a certain weight you’ll be at peace is a mirage, Freddie. You know that.

We have a phobia of weight gain. It’s no wonder, in your case. The press were so cruel and no one sat you down and advised you on how to handle it. You were young and alone and under a lot of pressure. Things are different now. You are older, wiser and have contributed to a world that is starting to treat mental illness with the reverence it deserves.

I really, really hope that you decided to commit to treatment with Dr Naseem at the Maudsley Hospital. I know you’re scared of going back to being “a fat lad” and the trauma associated with that point in your life. That fear needs to be unpicked because it’s about more than it seems. I don’t mean to sound like I know it all. I definitely don’t. I just want you to know what it’s like to be healthy. Everyone deserves good mental health. Everyone. Nothing compensates for it: not family, not a career. You deserve to be well.

I want to end this letter the same way I started it, by thanking you. You told Dr Naseem that you were worried about reactions to the programme. “You’re making yourself vulnerable,” she said. “I don’t like being vulnerable,” you replied. “Nobody does. I think it’s a skill that can be learned.” “Can it? I don’t know if I want to learn it.”

Freddie, that vulnerability is so powerful. It connected to a part of me that hardly ever receives oxygen and now I am speaking about it too. You’re unearthing a new language, one so close to the bone that it hurts to excavate, that will give people who suffer, their loved ones and anyone on the cusp of bulimia a goldmine of perspective.

Thank you for that.

Look after yourself, please.

Love, Sophie

Freddie Flintoff: Living with Bulimia is available now via BBC iPlayer.

Published 10 Oct 2020

Craig Roberts’ second feature, about a woman copying with schizophrenia, allows us to share its protagonist’s experience.

Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead are films of hunger and the frustration of bodies.

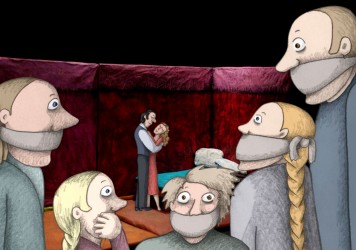

Signe Baumane describes her journey from a Soviet mental hospital to director of animated feature, Rocks in my Pockets.