Few companies found such malevolent horror in the quotidian of domestic life as Amicus Productions. Far from the castles and dark woods of other horror films made in the 1960 and ’70s, Amicus instead looked to living rooms, basements and kitchens for their particularly grimy but enjoyable form of horror cinema. With the restoration of two of their classic films, Peter Duffell’s The House That Dripped Blood and Roy Ward Baker’s Asylum, now is the perfect time to revisit these unusual, entertaining and often no-holds-barred horrors, noted for their balance of witty black humour and genuinely macabre punch-lines.

Amicus was the brainchild of Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg. Though originally making teen musicals, they soon saw the potential of horror thanks to their eventual rivals, Hammer Film. In many ways, Amicus came to embody another side of horror that had increasingly shrunk thanks to Hammer’s success. Whereas the latter devoted the majority (though not all) of their output to Gothic period horror, Amicus focussed on the bizarre modern day, producing films that celebrated the latest fashions and quirks of British life with such relish that they feel themselves like period pieces today. Britain here is a byword for Surrey and the Thames Valley; an eerie place filled with waxwork museums, antique shops and psychiatric wards.

Although the studio sometimes made single narrative films like The Skull and I, Monster, Amicus became renowned for its portmanteau features, foreshadowed by the Ealing film, Dead of Night, and often detailing several stories told by people connected by a singular location. Whether locked in vaults or asylums, trying to investigate mysterious houses or fairgrounds, or even simply passengers in the same compartment on a train journey, short horror stories seemed aplenty in the Amicus universe, with everyone possessing their own ghastly tale to tell.

These films hark back to horror’s roots, found within the short story or novella, recognising the excellent fit that horror narratives found within the stricter form. The films here are two of the three written for Amicus by noted horror writer Robert Bloch of Psycho fame which further attests to the merit of the form.

Even with occasional forays into the unintentionally silly, Amicus always cast their films brilliantly and relied on a wealth of top level performers. In fact, the sheer calibre of actors the studio managed to attain for their films is still a surprise in hindsight. In just the two films discussed here, the studio secured roles for Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee, Denholm Elliott, Richard Todd, Sylvia Sims, Patrick McGee and Herbert Lom to name but a few. Even Charlotte Rampling is seen in an early film role in Asylum, acting opposite Britt Ekland as her murderous inner self. If seen as sometimes falling into the utterly absurd, the studio at least never failed to amass fine casts to bring a sense of seriousness to its tales.

Due to the structure of Amicus’ films, their style varied enormously, rather like reading a horror anthology by differing authors. However, when the stories really work, they tend towards an incredibly dark, grimy vision of what could be called the Domestic Gothic. Similar in atmosphere to films such as Whatever Happened To Baby Jane?, The Nanny and Frenzy, the Domestic Gothic made the most of ordinary (and in hindsight, kitsch) home settings, building on the gleaming, garish excesses of the newly emerged consumer society.

Detailing obsessions with home furnishings, emphasising lurid wallpapers, and implying seedy suburban affairs, Amicus’ Domestic Gothic is a particularly effective caricature of Britain in the early 1970s; mixing cheese and pineapple hedgehogs with murderous mayhem. They’re the halfway point between The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Abigail’s Party.

In the ‘Frozen Fear’ segment from Asylum, this domesticity is most obvious. The story follows an adulterous man luring the wife he is cheating on to the basement of their plush house to show her a new freezer, only to decapitate her and put her in it limb by limb. The narrative barely leaves the rooms, as the dismembered body parts come to life and gang up on the murderer and his mistress.

Asylum is an especially dark collection of stories for Amicus, missing the lighter episode that typically injected a moment of dark comedic relief into their films. Instead, the viewer witnesses possessed mannequins brought to life by a suit of cursed material, an ill woman who commits murder as her alter ego, and an inmate who believes he can transfer himself to bizarre mechanical dolls.

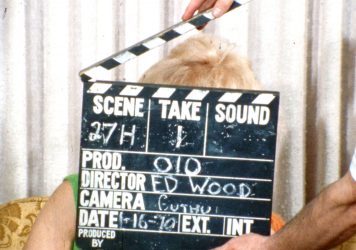

If this is all sounding rather macabre – and certainly Amicus’ work with Bloch is frequently bizarre and grimly menacing – The House That Dripped Blood shows an entirely different side to the studio. A technically weaker film, Peter Duffell creates a knowingly camp, self-aware satire with an emphasis on garish details; something akin to Carry On Screaming. Set in a house where terrible things have happened, the film portrays handily horror-fluent tales that have taken place in its admittedly blood-free walls: a horror writer is haunted by a psychopath he has created for his latest novel; a young girl is dabbling with witchcraft and taking revenge on her strict father; and a man is slowly possessed by the likeness that a waxwork dummy shares with his lost love.

Most enjoyable of these shorts is ‘The Cloak’, which makes light of Vincent Price and his infamous trouble with Michael Reeves during the making of Witchfinder General. It follows Jon Pertwee as famed horror actor Paul Henderson, accompanied by Ingrid Pitt in some of the campest images in all of ’70s cinema. The actor, with frilled shirt and cigarette holder, becomes worried about a cloak he has bought and its strange qualities, seeming to turn him into a vampire.

It’s a knowing jibe at the more Gothic excesses of Amicus’ rivals, but equally comes off as a silly but introspective mission statement regarding the studio’s determined grounding in the present day. “That’s what’s wrong with present-day horror films,” suggests Henderson, “there’s no realism.” Amicus couldn’t have been clearer as to their mischievous intent.

The House That Dripped Blood and Asylum are released on 29 July via Second Sight.

Published 28 Jul 2019

By David Hayles

From Charles Bronson to Chuck Norris, David Hayles offers an indispensable guide to the cult production company.

By Anton Bitel

Eugenio Martín’s Horror Express is like a locomotive mash-up of The Thing and Murder on the Orient Express.

By Will Sloan

The cult director’s long-lost sexploitation comedy is finally being released on home video.