We all hope for redemption in one way or another, a chance to overcome our injustices to look at our persecutors square in the face and declare our perseverance. After Jules Dassin was unceremoniously blacklisted from Hollywood in 1950 and unjustly shamed by the industry and his country, he made such a declaration in 1955 with Rififi.

On its surface, this was an intricately composed heist drama, which Roger Ebert later credited as, “the invention of the heist movie.” Its fingerprints are all over the likes of Brian De Palma’s Mission Impossible, Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing, Michael Mann’s Heat, and even Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Doulos. Underneath its surface, however, Rififi is an intricate collection of personal principles – a direct response to those who deemed those principles a threat.

When a jewel thief named Tony is released after a five-year prison sentence – a parallel to Dassin’s five years of unemployment after blacklisting – he is reteams with Jo, the man he took the fall for on their last job, and two other friends, Mario and Cesar (Dassin himself), for another heist. Ubiquitous in its references to Dassin’s trial and removal from Hollywood, the film’s moral core is tethered to ideas of sacrifice, honour and trust.

It may seem ironic to consider moral obligations in the context of a group of thieves, but by having his central characters be anti-heroes, Dassin turns morality on its head, muddling the term so as to make us question its definition and more importantly who is defining it?

In a frank and rather heartbreaking interview, Dassin mentions that in the period between Night and the City and Rififi, there was a testing of wills which used labor to pin many industry people against their own. “Your wife would say, we don’t care about your principles, think of your family,” Dassin recounts of the time. It’s a common tactic of the powerful to use money as a cudgel to break principles and fellowship. When the four thieves sit at the table with the jewels from the safe sprawled out, they each questions what they will do with the money. Tony says he doesn’t know. Perhaps he fears that it’s the money in the end that will decide what to do with him.

The lack of money for Rififi is reflected in the film’s production and perhaps was the engine that steered its quiet brilliance. A film about a ragtag bunch was also made by a similarly down-on-their-luck group. Jean Servais, a French actor who’s reputation was spiralling away through his alcoholism was picked by Dassin in lieu of much more expensive actors which the budget couldn’t afford. The film cast and crew was populated with friends and friends of friends who would agree to a low salary out of friendship with Dassin. The lack of funds also lead to Dassin having much more creative control over his own project than his Hollywood output, casting himself as a major part of Cesar and scouting all of the locations himself.

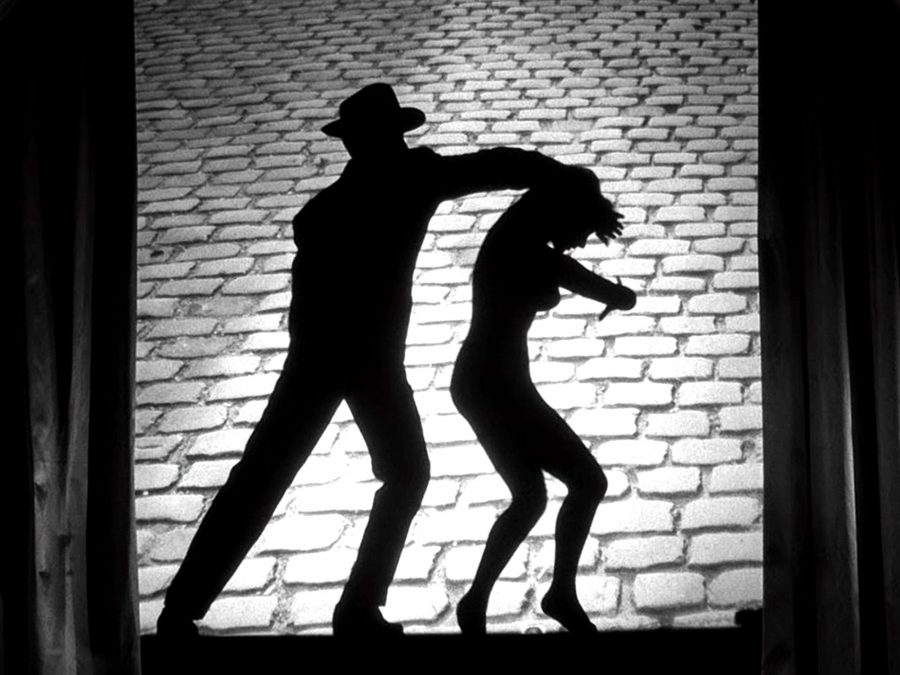

The thinking that went into Rififi, for which won Dassin the Best Director prize at Cannes, is evident in the meticulous construction of its famous central heist, featuring no dialogue or non-diegetic sound. The heart of the film is evoked in Dassin’s many ideological narrative decisions like stripping away the source novel’s unsavoury sequences involving in one instance, necrophilia, and its racist elements that pin Euro protagonists against Arabs.

Dassin could have easily taken direct shots at his enemies by making the villains Americans, but he instead opts for more nuanced and subtle jabs, like characters backstabbing each other, turning on oaths, and paying a steep price for lies which elude to the moral failings of the Hollywood industry that left him out to dry. The same industry, in a great twist of irony, that would be immeasurably influenced by his masterpiece.

Published 21 May 2020

Before Mike Hodges and Michael Caine, there was Masoud Kimiai and Behrouz Vossoughi.

By Tom Williams

The director critiques society’s voyeuristic tendencies in this Hitchcock homage from 1972.

By Rich Johnson

Samuel Fuller’s murder mystery captures the fear and paranoia which beset postwar society.