Despite having almost two thousand followers to her own name, Liza Mandelup doesn’t follow a single person on Instagram. It was a tricky decision to make, particularly as someone who came up as a filmmaker online and cherishes the communities and the space for her work that she found there. “I’ve pulled back a lot since I started to think about who is in control of my emotions,” explains Mandelup. “I want to be in control of my emotions.”

She continues, “We’re at a time where people consume without thinking about that too much, and they don’t understand how a good day can shift from a bad day just because of something they saw on social media. We consume like it’s good for us, and it’s not necessary.”

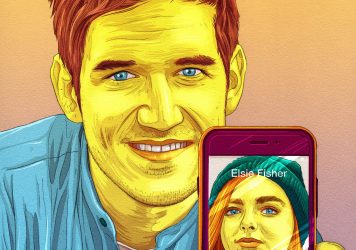

This complicated truth is the centre of Jawline, a feature-length look at the emotional economy of the internet. Mandelup began shooting the project at the end of 2015, when she started researching fan meet-and-greets. Eventually, she came across her star: Austyn Tester, a 16-year-old nano-influencer from rural Tennessee. In a parallel narrative strand, now-infamous talent manager Michael Weist provides a counterpoint to Tester’s wide-eyed innocence. We see the 19-year-old snapping at his clients in the minimalist Los Angeles mansion in which they all live together, pleading with the younger teens to film their sponsored content on time.

As Tester gains traction online, Mandelup helps us navigate his specific slice of the social mediascape, populated almost entirely by Gen Z teens. This is the Instagram-adjacent land of live broadcasting, where the distance between fan and creator has never been slimmer.

Teen fangirls clamour after the boy broadcasters in convention centres, shopping malls, and through video portals on YouNow with the fervour of Beatlemania. Through a series of interviews, the why of their admiration becomes clear – the platform, and a lack of age difference, has allowed for an artificial intimacy to form between viewer and performer. For one fan, these boys are “the friends I never had, and wish I had”. Another notes how the medium lets you “feel like you have a family”. A third explains how she had to handle life alone when her parents began experimenting with narcotics, but that she’s glad that her younger sister was fortunate enough to have broadcasts to turn to when the situation began to affect her life.

Mandelup originally planned to feature only one fangirl in her film, but changed her mind when she realised their viewpoint was better represented in an ensemble. “I always felt like a lot of his fangirls were trying to escape something in their life. They just wanted something that would take them out of the day-to-day struggle, and give them this alternate version of their present, something that made them feel hopeful.”

Depicting the precedence of screens in the lives of these girls was one of Mandelup’s biggest challenges. “For me, the answer to that was: the internet and social media represents a fantasy. So I was thinking about ways to elevate people’s relationships to social media as people’s relationships to their hopes and dreams, and that lends itself to a lot of imagery. Everything was about creating this dreamscape.”

What we see of the broadcasts themselves is a relentless slew of positive aphorisms. The boys pepper the girls with compliments and questions about their day, assuming a role that is part-therapist, part-boyfriend. It may raise alarm bells, but Mandelup is hesitant to give the situation a moral valence. “People try to ask me if it’s good or bad for them to be following these live broadcasters, and it’s not really that easy to answer. If someone can give you a sense of community and purpose when you don’t have that otherwise, that is not a negative. On the flipside, you can go too deep into that side of yourself, and lose touch with what your actual life is.”

Certainly, the tendency to over-focus on fangirls’ vulnerability denies them a degree of agency. “I think you have to give some credit to these girls. They know what is cool and what is not. They ultimately are the ones who decide who sticks around.”

Jawline is available to watch via Hulu and in select US cinemas from 23 August.

Published 21 Aug 2019

The likes of Raw, The Transfiguration and others speak directly to self-aware, socially-conscious teens.

We slide into the DMs of the director and star of the year’s must-see middle school movie.

By Sarah Jilani

Black Code follows “cyber stewards” from Toronto’s The Citizen Lab.