1967 was a pivotal year for Hollywood. Films like Bonnie & Clyde, In the Heat of the Night and The Graduate signalled the beginning of a new era for major studios. Young directors were given new independence to embrace the changing attitudes of the decade; their films characterised by both formal experimentation and conceptual audacity. Even 50 years later, many of these films have startling resonance. But perhaps none are as strange and exhilarating as Point Blank.

Ostensibly, this hardboiled crime-drama follows a conventional revenge narrative. But British director John Boorman, making his first US production, approaches the material with probing eccentricity. As well as the murkier corners of classic film noir, Boorman drew inspiration from art photography and the French New Wave, including Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, which was itself ‘speaking back’ to American crime movies. Such a transnational ping-pong of cultural influences results in a film experience that feels at once familiar and bizarre.

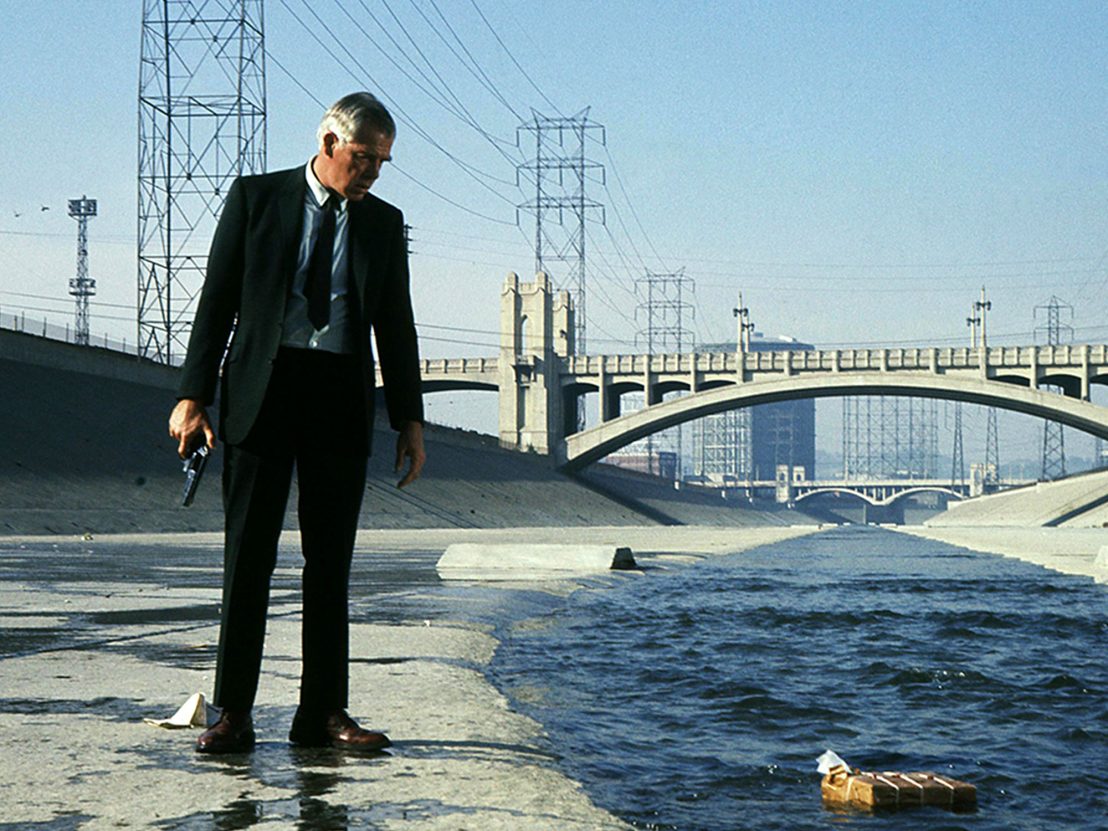

Lee Marvin plays Walker, a thief who is double-crossed by his partner and left for dead. He vows vengeance but finds that he now must contend with a mysterious corporate hierarchy whose true size and shape he can never quite work out. The Los Angeles he navigates is, in Boorman’s words, “an empty, sterile world”, all bright lights and hard edges that leave nowhere to hide. It’s a descendent of the seedy cityscape of Raymond Chandler, only more corporate, more anonymous, and more hostile to one man working alone.

Marvin was never better than he is here. Walker is an unsmiling, gravel-voiced antihero who is impossibly tough and, as his name suggests, unstoppable in his single-minded pursuit. Some hard men feel the need to grunt and growl, but so much of Marvin’s menacing power comes from the fact that he doesn’t. When Walker decides to visit his wife Lynne (who left him for his double-crosser), Boorman cuts between mirror shots of her and the stern-faced Walker pacing down an empty corridor, until his even footsteps form the percussion of a rising crescendo on the soundtrack.

Eventually, he bursts into her apartment, fires six bullets into her empty bed, and then takes a seat. A dialogue scene follows – though only Lynne speaks. In the script Walker has lines, but Marvin’s performance is so effectively minimal that he knew the scene worked better without them. Such audacious experimentalism is rare in genre cinema, but it saturates almost every shot.

What distinguishes Point Blank from other revenge thrillers is its dreamlike, otherworldly tone. Cinematographer Philip H Lathrop cut his teeth working with Orson Welles, another denizen of weird Hollywood, and here he conjures dramatic widescreen compositions that at times veer into the avant-garde. The chiaroscuro style of postwar noir is transplanted into the highly-saturated colours and dramatic patterns of the 1960s, creating a remarkably vivid visual style. Lathrop’s use of reflection and light renders Los Angeles an eerie and glassy space that doesn’t quite seem real.

In one memorable nightclub scene, Walker fends off some goons during a backstage brawl while vivacious funk singer Stu Gardner riles up a raucous crowd out front. Dramatic close-ups of the audience are intercut with the violence, blurring the line between pleasure and pain. The combination of Gardner’s music, Marvin’s stoic performance, and the psychedelic lava lamp lighting gives the sequence a hypnotic energy.

Moreover, the film boasts an unusual treatment of time, including flashbacks with a poetic rather than narrative motivation and an innovative use of slow-motion that precedes Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch by two years. It’s an intensely subjective style, and one that has produced the theory that the revenge story is in fact Walker’s fantasy as he lays dying.

These are bold ideas that critics were unsure of at the film’s release, but Point Blank’s influence on cinema is hard to understate. The struggle of the individual to retain his autonomy in a corporate landscape certainly resonated in 1967, not least for the young New Hollywood auteurs who were handed the keys to the city by studios looking to innovate. Since its release, a host of prominent directors who spin movie poetry from pulp fiction – Steven Soderbergh, Nicolas Winding Refn and Michael Mann cheif among them – have consistently drawn from Point Blank for its effortless blend of cool, smart and weird.

Published 23 Sep 2017

Is it possible for women to love movies which promote a regressive, misogynistic worldview?

Arthur Penn’s seminal crime thriller owes a lot to the likes of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut.

Sidney Poitier confronts violent racists in smalltown Mississippi in this sweat-dappled 1967 policier.