The original cast and crew discuss the making of this short-lived follow-up to Twin Peaks.

A man stands in the corner of a kitchen, rooted to the spot in fear. Cue some uptempo jazz music, which is promptly cut. A woman enters the room, curtseying stiffly, and motions at the man to leave. He starts to run, but his braces get caught on a cupboard and he’s flung backwards out of a window. The woman screams. Then a man with a gun appears at the door. “I caught you with another man!” he yells. But there is no other man.

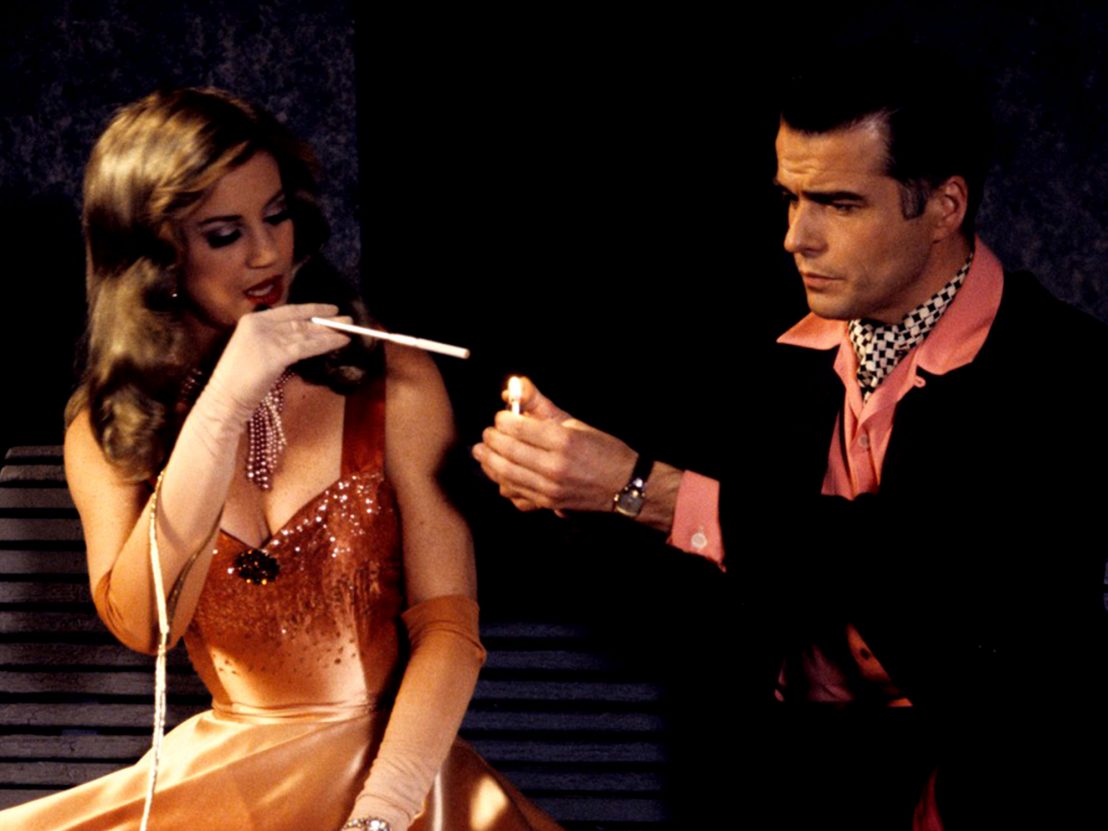

This scene is as strange and outlandish as any to have sprung from brilliantly surreal mind of David Lynch, but there’s something wrong with the picture. This is On the Air, the ill-fated sitcom Lynch and Mark Frost conceived as a follow-up to Twin Peaks. Dumped by ABC just three weeks into its seven-episode run in 1992 (it aired in full in the UK), the comedy follows the cast and crew of a ’50s light-entertainment show that becomes a hit though a series of happy calamities on-set – parallels definitely intended.

And if a half-hour sitcom seems like a strange departure for the man behind Blue Velvet and Mulholland Drive, well, you’d be half right. On the one hand, On the Air is slapstick, silly, and surprisingly broad in tone, right down to the overuse of comedy sound effects. On the other, it features a dreamy score from Angelo Badalamenti, on a break from composing the theme music for the Barcelona Olympics, and just enough inspired nuttiness to justify the billing.

Nancye Ferguson, who plays go-getting production assistant Ruth Trueworthy, recalls her experience working on the show to LWLies. “For me it was like, ‘A David Lynch comedy? How amazing is that! What could it possibly be?’” she says. “I didn’t see it as a departure. There’s a darkness to David’s work, but he always sees the light no matter how dark you go. Like with Twin Peaks, yes, it’s dark, but there’s this delightful side in a lot of moments, which is pretty much David when you see how he is as a human being.”

To anchor their new show, Lynch and Frost brought in two Twin Peaks’ bit-parters, Ian Buchanan and Miguel Ferrer, as The Lester Guy Show’s washed-up star and bullying network executive Bud Budwaller respectively. Both play outsize comedic riffs on their characters from Twin Peaks, thespy love interest Dick Tremayne and the majestically rude FBI pathologist Albert Rosenfeld. (David L Lander AKA Tim Pinkle also returns as Vladja Gochktch, the show’s vowel-mangling European director.)

“I think Dick Tremayne would probably in his madness base himself around someone like Lester, but for me it was kind of an extension of that character,” says Buchanan in reference to his role on the show, which mostly involved having various indignities heaped upon him in his attempts to outshine co-star Betty Hudson (Marla Rubinoff). “At the time I’d been doing soap opera romantic leads and that kind of thing, so it was a nice break for me. I liked the opportunity to play a very bad song-and-dance man, I thought that would be kind of challenging!”

In the brilliant Lynch-directed pilot episode, the transition from funny-peculiar to funny-ha-ha seems more a question of emphasis. Later in the kitchen scene, the woman – an actress performing in The Lester Guy Show – screams again, which we now know is the gunman’s cue to burst through the door and surprise his cheating wife. This time, there is another man – it’s Lester Guy, swinging upside-down from a rope tied round his ankles. Lynch keeps returning to the image, letting it seep into your brain.

“David directs with such ease,” says Ferguson, whose character was reportedly based on Lynch’s future wife and editor on the show Mary Sweeney. “He’s very specific but [when something worked] he’d be like, ‘That was a gosh-darn good take!’ He has these wonderful expressions. It was all done with joy, and it really felt like we were in an elevated state a lot of the time. David is a brilliant artist [but] he’s also an exceptional human being with an amazing kindness and heart, his world is so specific [that] you really feel like you’re part of something.”

Like any good surrealist, Lynch knows that a door is never really a door, just like a pipe is never really a pipe. In a scene of primal terror from the new series of Twin Peaks, there’s an insistent thumping at a door as Agent Dale Cooper tries to escape from existential limbo. “You’d better hurry,” says a woman with no eyes. “Mother is coming!” Unlike in the gunman scene from On the Air, here the door is an unsettling rather than a comedic device. But its basic ‘meaning’ is the same: the door is where the id gets in, threatening to unleash the forces of chaos on ordered reality. (In Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, Freud formulates a theory about humour that echoes his theory of the uncanny – essentially, both have to do with the return of repressed thoughts and desires to the conscious brain.)

If the pilot set the bar impressively high, what followed was, quite literally, history repeating itself as farce. The network buried the show in a 9.30pm summer slot and, with Lynch taking a back-seat on all bar one of the remaining episodes, quality control nosedived accordingly. Still, there’s a frantic energy to all of the episodes that occasionally tips over into the bizarre, like the scene where Lester has to make out with a puppet called ‘Mr Peanuts’ because his leading lady has fallen down a well. “When I look back on it, I think parts were really clever and inventive,” says Buchanan. “There’s an episode that came in slightly long, and rather than trim it or cut it I think it was just sped up a little bit, which I think is just very, very funny and a great way to handle it.”

Ferguson was convinced the show was going to be a hit. “There wasn’t anything in my mind that didn’t think we were going to be on the air for a really long time,” she recalls. “I remember David saying, ‘Well, you know what happened with Cheers!’ I was like, ‘We’re in!’”

Whatever its flaws, On the Air did point up some intriguing new possibilities for television – the now-fashionable lack of a laughter track, for one, and the postmodern show-within-a-show setting, beating 30 Rock to the punch by nearly 15 years. It’s also striking how Lynch and Frost chose to follow up a show that decisively rolled back the frontiers of television with one taking the piss out of its parochialism.

Moreover, it’s revealing that ABC were so quick to bail on a show from an established director who’d recently handed them their biggest ratings hit since Dynasty. “The networks at the time really didn’t know what to do with an artist,” says Ferguson. “Today a show like On the Air could be nurtured by a Showtime or an HBO – a small audience can be plenty for a subscription network, which can really let things exist for people to discover. It doesn’t always have to be this big blowout based on advertisers. I think it was way ahead of its time, and completely judged by a standard that should not exist for an artist working in television.”

During its brief but calamitous run, On the Air hinted at a world of no-rules television making that wouldn’t come to pass for at least another decade. As Buchanan puts it wryly, “David’s still the only director I’d hang upside down for.”

Published 14 Jun 2017

By Jack Godwin

The composer reveals the inspiration behind his iconic Twin Peaks score.

A pilgrimage to the sleepy American setting of David Lynch and Mark Frost’s iconic show.

By Greg Evans

If you recognise this scene, you’ll already know what’s coming...