Viewed from muddy, broken old Europe, Hollywood is a place where almost anything seems possible, not only in the sense of legitimate but also in the sense of magic, of things that go beyond common understanding. For instance, consider the fact that a well-known film industry couple of the ’50s and ’60s, Dominick Dunne and Ellen “Lenny” Griffin, named their daughter Dominique and their son Griffin after their first and maiden name respectively.

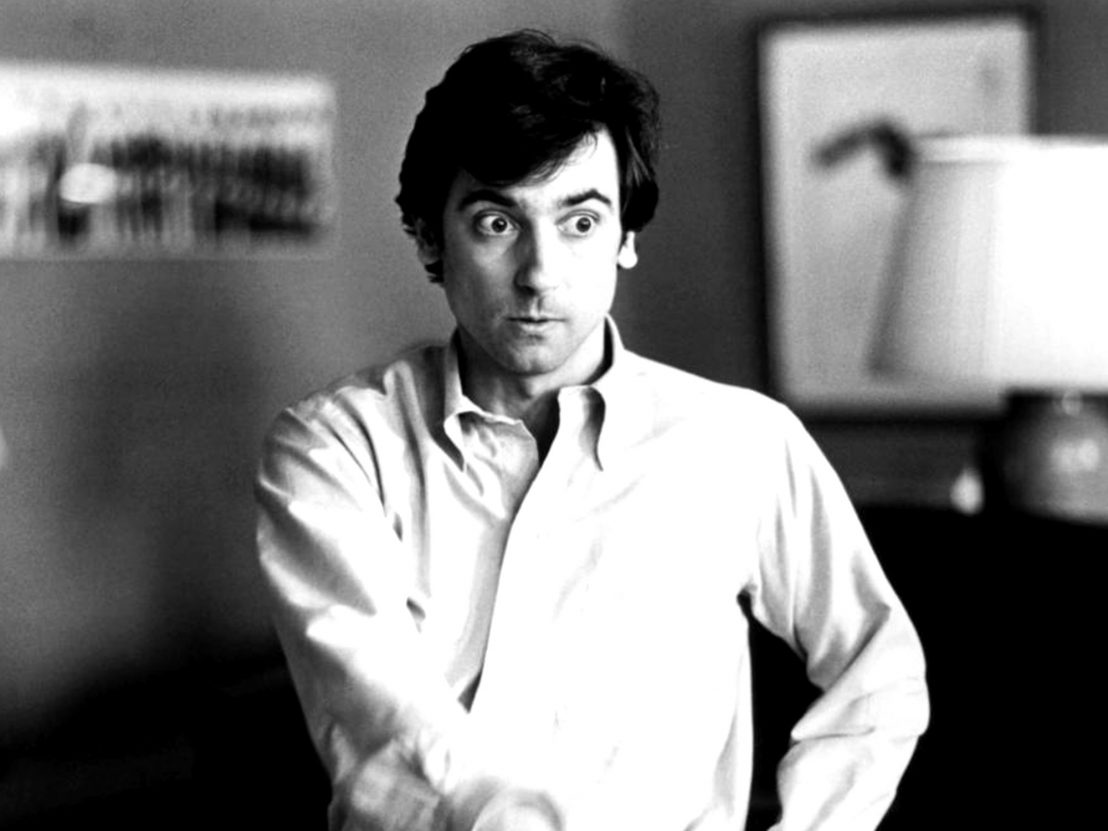

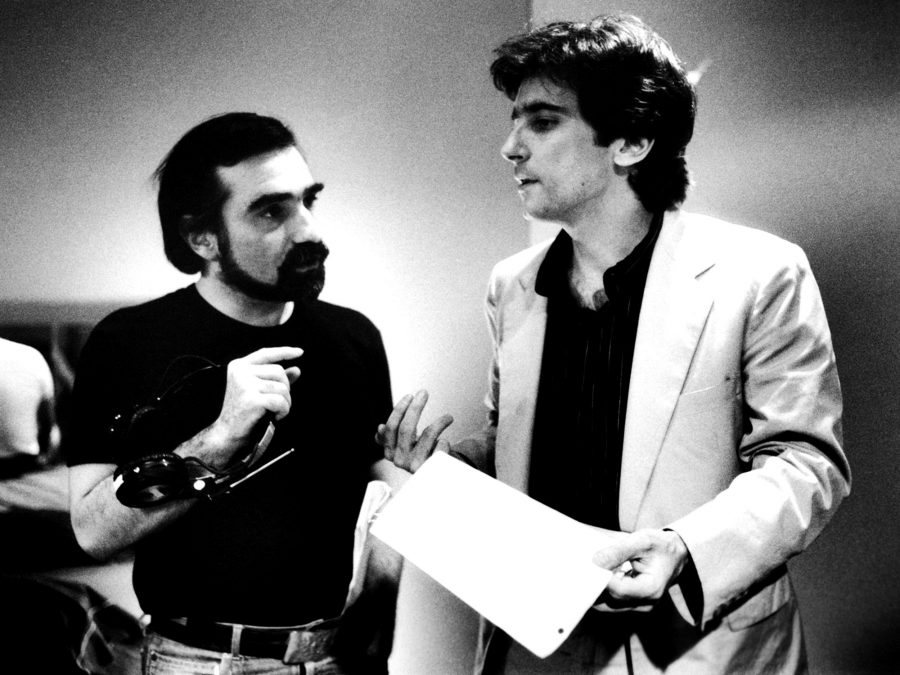

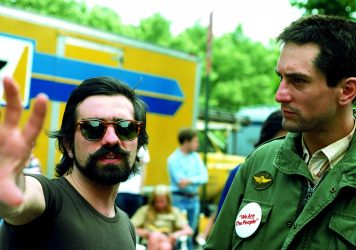

Thirty years after his birth, their eldest son, Griffin, was cast as the glorious protagonist of Martin Scorsese’s After Hours, on which he also served as producer. It was the first film Scorsese shot with Michael Ballhaus and his cinematography lent a raspy and improvised touch to Dunne’s turn as the guy who finds himself stuck into a whirling series of events over the course of one night in SoHo.

Following a handful of supporting appearances – most notably in An American Werewolf in London – Dunne’s first lead performance is not striking. but he is funny, charming and endearingly clumsy in his acting style. More than for its hilarious sketches and impressive glimpses of gentrifying downtown Manhattan (and Rosanna Arquette’s blinding beauty), After Hours remains memorable because its protagonist is just not what you would expect.

There is something odd about Dunne’s presence, just like there’s something odd in the development of this screwball comedy: you feel like it could go on for ever but it also urges you to take a break from it. He conveys familiarity there where he’s supposed to deliver comic relief, a trait later shared by his daughter Hannah. This too is strange, because the Dunne family had little to do with comedy and experienced a story so tragic, it can perhaps be endured only if treated as film material.

Griffin’s younger sister Dominique was also in the film business, making her first steps as an actress around the same time. After a few TV gigs, she became Poltergeist’s ‘older daughter’, transforming a throwaway line into the film’s most hilarious catchphrase, “What’s happeniiiing?!” That image of a 22-year-old Dominique screaming in dread could have been just another example of that weird, typically Dunne-ish sense of humour, had she not soon after been strangled to death by her ex-boyfriend just around the corner from Beverly Hills.

If now the name rings a bell, it’s probably because of Joan Didion. Dominick was Didion’s brother-in-law and he who brought the writer couple to Hollywood, helping them obtain their first gigs as screenwriters. The three of them later worked together on the biggest hit of John Dunne’s career, 1971’s The Panic in Needle Park. He had made a name for himself as a daring producer a year earlier, with Friedkin’s The Boys in the Band, a pioneering film for its depiction of homosexual characters and queer culture. But, after overseeing a minor Liz Taylor melodrama (Ash Wednesday) and the adaptation of Didion’s ‘Play It as It Lays’, in the ’70s his career went down the classic path – too many parties, too little work – of the Hollywood fall from grace.

Practically forgotten, Dominick Dunne kept a diary during the controversial trial of his daughter’s murderer and in 1984 Vogue published a renewed and thorough report of the events. From then on Dunne reinvented a successful vocation as a gossip columnist – “He knew everybody” – and crime reporter, notoriously covering a court case very similar to that of his daughter: the OJ Simpson trial.

With his father back on track, Griffin Dunne experienced a similar trajectory, albeit one scattered with more frequent and less dramatic ups and downs. While he had more or less framed his career as an independent, he crossed paths with big names without ever really becoming one: Madonna, Sidney Lumet, Dolly Parton, Uma Thurman, Sandra Bullock, Luc Besson. Though he covered different roles in the industry, Dunne was however mainly active as an actor. Then, from the mid-90s, he took over the whole set.

Perhaps inspired by his random mingling with the star system, his most successful works as director (the Oscar-nominated 1995 short Duke of Groove and Lisa Picard is Famous from 2002) reflect a chaotic ensemble of cameos, comedy-romance and mockery bordering on obscenity (let’s not forget that Dunne starred in the English adaptation of Io e lui, an Italian porn-ish feature in which a film director suddenly has to deal with his own speaking penis).

Most recently, Dunne has reemerged as one of the stars of Jill Soloway’s Amazon series I Love Dick, playing Sylvère Lotringer, a Holocaust scholar and husband to Chris Kraus (Kathryn Hahn), a neurotic video-artist who falls for Kevin Bacon’s eponymous land artist. This combination – Dunne, intellectualism and sex – appears all the more apt and entertaining if we think of the original Lotringer, who in real life is the founder of the seminal publishing house Semiotex(e). The series successfully translates the experimental and feminist novel by the same name into an accessible plot-based series without losing trace of its main themes (sexual objectification of a man by a woman, the jeopardising mixture of art and academia and the role of gender in these fields).

And to draw this celebration of the Dunnes to a close, it’s worth mentioning that Amazon is presently home to another talented Dunne, Griffin’s daughter, Hannah, who stars in Mozart in the Jungle. The perfect comic sidekick to Lola Kirke’s protagonist, she is the impulsive but reasonable friend who makes radical life choices while fixing up your everyday mess. Supported by an energetic voice and chirpy brown eyes, she looks at ease on screen in a way that her father never did. Regardless of whether or not her comic vein is hereditary, sometimes it’s worth digging through Hollywood’s lesser-known dynasties.

Published 19 May 2017

In Jill Soloway’s hit show, women’s emotional outbursts are crucially not stigmatised as “hysterical”.

A comprehensive guide to the directing credits of this great American auteur, from Mean Streets to The King of Comedy to Killers of the Flower Moon.

The titan of big screen comedy is at his understated, singular best in Hal Ashby’s tale of a simple-minded gardener.