Man… where to even start? I was given an assignment at a previous job to write about the films of Nicolas Roeg for a season at London’s BFI Southbank. The problem was, I’d only seen a couple of them (Walkabout and, strangely, Track 29), so carved out a block of duvet time to sail through the canon in chronological order. I was scintillated by what I saw, and with each film I watched I seemed to have a new personal favourite. The sensuality, the editing, the hallucinatory sounds design, the violence… The one that I was a little unsure of way back when was 1976’s The Man Who Fell to Earth, based on a novel by Walter Tevis and starring the rock icon David Bowie who, in the music world, was teetering on the precipice of his creatively fecund ‘Berlin’ era.

As he had done with Mick Jagger in Performance and, later, Art Garfunkel in Bad Timing, Roeg was proving himself a master of benignly leaching off of the inherent talents of musicians and channeling them into an on-screen mood. You’d be hard pressed to claim that these stars delivered great performances in the traditional schema of movie acting, but their very presence – their essence – is what made these films idiosyncratic and, by extension, memorable and great.

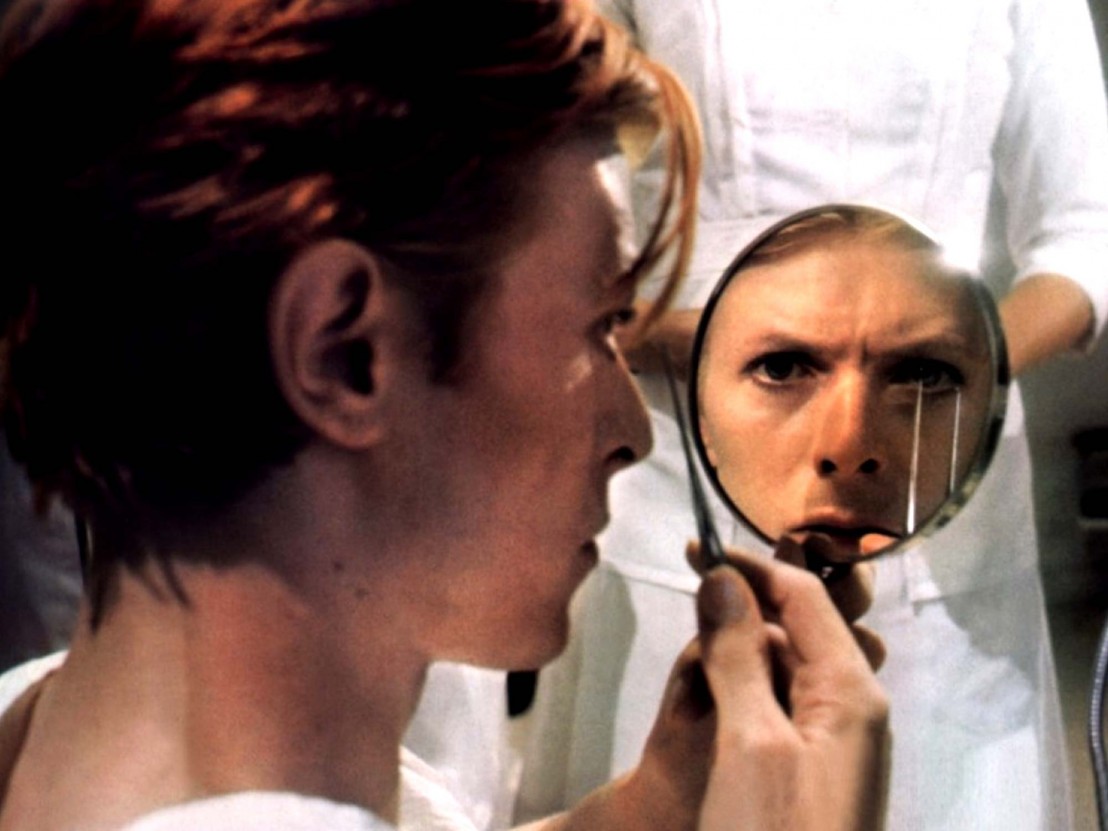

In the interim since completing that assignment, The Man Who Fell to Earth is the Roeg film I’ve returned to the most often, as it feels like this monolithic edifice that’s too mighty to mount on single pass. Though the story is about an alien bestowing superior technology to Earth’s scientists as a long-shot method of saving the people of his own desolate, faraway planet (and succumbing to depression and alcoholism in the process), it’s a more edifying work if taken as a shot of pure emotion. Bowie plays the willowy, ageless starman who dubs himself Thomas Newton and swiftly goes about executing his elaborate mission. Though he doesn’t do anything as gauche as to express it directly, the unyielding pain of his character is present from first frame to last.

Sweep aside the nation-critiquing intimations of the film, its vicious attacks on American commerce and the homogenisation of culture at that time, and what you’re left with is a bittersweet portrait of rock stardom and the social cocoon that comes as part of the lifestyle. A blessing, a curse, a dream, a nightmare. Bowie’s penetrating otherness in the film – often overlooked by other characters because of his status – is what makes it so moving and so honest. By placing him in the lead role, the film strays from its science fiction roots (is it the least science fictiony science fiction movie ever made?) and becomes a more cerebral and delicate study of what it means to be disconnected and alone.

The film’s tragic ending sees the alien alienating his human paramours through his understandably erratic behaviour and an inability to comprehend that he’s been chewed up and spat out by a capitalist system which operates not on benevolence, but on suffering. Roeg described the film at the time of release as “a mysterious American love story”, and it’s a love story between the American populous and its chosen idols, however eccentric and fragile they may be. Perhaps only matched by Björk in Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark, Bowie’s performance in The Man Who Fell To Earth doesn’t just make the film, it is the film. If you’re hastily charging the film of incoherence, then you’re doing it wrong, just as I had way back on assignment deadline. With anyone else in that role, the film would simply not exist as it is.

Bowie went on to act in a number of other movies – I’m sure his role in Labyrinth will get its dues elsewhere, but he was also perfectly cast in Nagisa Oshima’s Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence (a film which dealt with latent homosexuality and gender fluidity in a Japanese POW camp) and David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, in which he wears an over-sized white sport suit and buttoned down Hawaiian shirt like he was born into them.

It goes without saying that all these films will take on new resonance now that Bowie, at the age of 69, has succumbed to cancer and left the world in a state of confusion and grief. All death is sudden and unexpected, however much warning you have, but Bowie felt like someone who was always just about to get started. The Man Who Fell to Earth stands as his most sublime cinematic legacy. It’s maybe too much of a stretch (and too morose) to see it as the closest thing we have to a screen biography, but it works as a portrait of a man who existed on slightly higher frequency from the remainder of humankind, but craved inclusivity. As many have already stated on social media, we should feel privileged to share a world with Bowie. How we’ll adjust to a post-Bowie world is anyone’s guess.

Published 11 Jan 2016

By Jordan Cronk

Jordan Cronk recalls the moment he discovered the work of the late, great Belgian filmmaker.

It’s possible for a movie to have a positive impact on society and the individual.

Todd Haynes’ Carol is being celebrated as a queer classic, but what does the term “queer cinema” mean today?