“The sky was always grey, the rain was grey, the mud was grey and I was grey.” That how Alfred Hitchcock once described London. It sounds disparaging, but the former Eastender clearly had a lot of affection for his hometown: after all, it characterises so many of his films. His 1927 film The Lodger was even named after it; ‘A Story of the London Fog’, highlighting the role the capital plays in creating the story’s sinister atmosphere.

For Hitchcock, place was as important as the other parts of the script. Rope, Rear Window and Lifeboat all show the claustrophobic tension that can build up within one single location, but the director’s films are about expanses as well as confines, events ballooning out into grand climaxes, usually involving a major landmark.

After The Lodger’s titular mist, Hitchcock’s sightseeing trend began with Blackmail. The film ends with an exhilarating sprint across the roof of the British Museum. Smartly screened by the BFI in the museum’s own courtyard, we see Tracy (Donald Calthrop) dash down Great Russell Street, nip through the gates, pause by a water fountain and then enter the building. What follows is an extravagant chase in between artifacts and past rows of books. These background details add a huge frisson of excitement to events. Sitting in the courtyard, you could swear everything was taking place behind the doors at that very minute. But, amazingly, none of it ever did.

Instead, Hitchcock sent in a team of photographers to capture the various rooms. These pictures were then reflected onto 45-degree mirrors for filming and parts of the silver were scraped away to make room for doorways or props. A bravura bit of special effects work, but you’d never know just by looking at it. Constantly flashing his lens about, Hitchcock was no slouch when it came to such trickery. He used a similar effect for Strangers on a Train years down the line, back-projecting an image of that wildly spinning carousel – in reality a miniature – in front of which Guy (Farley Granger) and Bruno (Robert Walker) fight to the death.

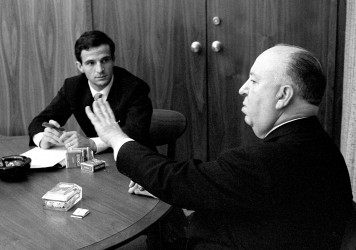

But sometimes you can’t substitute effects for the real thing. Part of the carnival climax uses a real merry-go-round: when an onlooker frantically tries to stop the whirling machine. “That little man actually crawled under that spinning carousel,” Alfie confessed to Truffaut. “If he’d raised his head by an inch, he’d have been killed.” He added: “I’ll never do anything like that again.”

You can tell, though, that the mad dog wanted to.

As the years went on, his location scouting became even more ambitious. In 1935, The 39 Steps zoomed from the Forth Rail Bridge in Scotland to The London Palladium for its on-stage finale featuring Mr Memory. (While the 1978 remake of the film got many things wrong, it ended in a surprisingly apt way, with Robert Powell hanging off the face of Big Ben – exactly the kind of crazy stunt Hitchcock would have pulled. It’s hard to believe he hadn’t tried it already.)

Go back one year and The Man Who Knew Too Much established Hitchcock’s relationship with spies. The man in question? Bob (Leslie Banks), who stumbles across a plot to assassinate an ambassador while on holiday in Switzerland. His child kidnapped, his wife scared, they venture back to old London Town to foil the murder.

Where on earth could such a suspenseful showdown take place? The Royal Albert Hall, of course. The imposing location was so fitting, in fact, that Hitchcock used it again in 1956 when he remade his own film starring James Stewart. In the leaner, superior original, the Master of Suspense relied on photos to recreate the interior scenes in a studio. In the remake, he had the chance to shoot more of it on location. He even begins it with a colour shot of the concert hall, eagerly showing us where we will end up. But fake or not, the effect is the same: each dialogue-free sequence, firmly rooted in the music filling the grand arena, is nail-biting stuff. No wonder, then, that the film acted as his calling card to America: a showcase of the director’s talent for crafting gems of cinema, locations and all.

Once in Hollywood, Hitchcock continued looking for bigger landmarks. In 1942, he made Saboteur, a film that climaxes with – you guessed it – someone falling off the side of the Statue of Liberty. That was another in-studio job, but the extravagant sight of a bloke dangling from the lofty torch instantly ignited interest from the press. “In the final five minutes, he chases the saboteur through a howling movie audience, with pistols barking on screen and off,” wrote The New York Times, “and finishes this wild and fantastic hue-and-cry atop – but hold! That’s a secret we won’t tell!”

Vertigo took a similar attitude towards San Francisco, playing on both the rising and falling of its hills as well as shooting scenes in the Palace of the Legion of Honor and, of course, at Fort Point. Here, the Golden Gate Bridge stretches into the distance, an ominous backdrop as Madeleine tries to drown herself in the river. Other locations were far trickier to snap. The United Nations rejected Hitchcock’s advances during the production of North by Northwest. The crafty coot’s response? To hide a camera in a van and film Cary Grant entering the building anyway – that’s how keen he was to show the genuine article on screen.

And yet all that trouble pales into insignificance when we see where Grant’s man-on-the-run is headed. How does one top falling from the Statue of Liberty? Alfie actually found the answer: clambering over Mount Rushmore. A studio the size of a warehouse helped Hitchcock recreate this monster, which soon became the base for one of the most famous movie climaxes of all time. Even Richie Rich imitated the sequence in 1994 – when Macauley Culkin’s copying your ideas, you know you’ve made it.

Rushmore. The British Museum. The Albert Hall. Why bother at all? Because Hitchcock knew what these landmarks add to a movie: realism. Just by seeing a recognisable place, audiences have a point of reference, a shared piece of knowledge. It’s the same logic behind the tracking shots that open his films, creeping from a known cityscape into an unknown interior. What quicker, more efficient way to anchor such far-fetched fiction?

Even away from the director’s chair, Hitchcock’s imagination was always looking for what a place could offer a plot. One sequence he dreamt up for North by Northwest was a tracking shot through a Detroit motor plant, following the production line as a car is assembled, only for the finished vehicle’s door to open and reveal a dead body. It’s that eye for locations that makes his thrillers both so exotic and so believable. “Local topographical features can be used dramatically,” he observed matter-of-factly to Truffaut, when discussing the backdrop of Switzerland in 1936’s The Secret Agent. “We can use lakes for drownings and The Alps to have our characters fall into crevasses…”

Hitchcock brought his roving gaze back to the UK for his penultimate film, Frenzy, flying down the Thames with a camera in tow as he lapped up the London skyline. Coming full circle, his topographical toying shows how innovative effects and practical production values can keep everything rooted in geography. Hitchcock’s films are typically about ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. The reason they all work? Because they happen in familiar locations. And as his early films show, when it comes to location, there’s no place like London.

Published 2 Mar 2016

By Iris Veysey

Her novels ‘The Birds’ and ‘Rebecca’ provided the perfect blend of moral complexity and Gothic drama.

By Adam Cook

Two grand masters come head to head in this insightful documentary from film critic Kent Jones.

By Jen Grimble

The director’s classic “one shot” thriller introduced numerous new and innovative cinematic techniques.