A new documentary about comic provocateur Gilbert Gottfried is one of the year’s most unexpected heartwarmers.

Gilbert Gottfried has the unusual honour of remaining a pop culture fixture more recognisable by sound than sight. An American stand-up staple since the 1970s, this “comedian’s comedian” has made a fortune off of his singular, Brooklyn-bred croak, which has given voice to everything from a conniving cartoon parrot to a screaming, insurance-shilling duck over the course of a nearly 50-year career.

In the flesh, Gottfried has crafted a short-fused, larger-than-life stage persona — defined by hunched frame, twitchy gesticulations, and that screeching, bellowing rasp — that thrives as a comedic device but also an element of disguise, designed to place focus on the wild, spotlit performer while averting our gaze from the famously private man who resides off-stage.

All of that changed, however, when Gottfried became, to the surprise of many, a husband and father in the late 2000s. Filmmaker Neil Berkeley has fashioned his new documentary Gilbert as a dual character study, chronicling the aging comedian and semi-newfound family man at this unexpected juncture in life. It is also, inevitably, an unmasking of Gottfried, who, like many comics of any generation, continues to identify as an extrovert in the limelight and an introvert in the real world.

Berkeley begins his film exactly as you expect him to, using a flurry of archival footage cherry-picked from across Gottfried’s career to convey that he has indeed been side-splitting since the beginning. As its basic structure (filled with talking-head interviews from Gottfried’s peers and sweet, casual footage of his life at home and on the road) takes hold, Gilbert quickly starts to resemble all those other fawning, hagiographic artist portraits that refuse to push their subjects toward tougher discoveries. There’s even the requisite moment in which comedy is described as an addiction, this time courtesy of Jim Gaffigan, who tritely declares, “Once you’re a comedian, you have that heroin in your system.”

But neither Berkeley nor Gottfried prove content with merely dawdling on the surface. What emerges is a film keen to plumb Gottfried’s eccentricities, like his self-admitted cheapness and hoarder habits, memorably visualised by the multiple boxes of hotel soaps and shampoos he stores in his home, one of the most indelible details of a traveling stand-up’s workmanlike existence. But director and subject are also united in exploring the darker shades of the latter’s life, accruing emotional depth by lingering on periods like Gottfried’s teenage years, in which he was a high school dropout who never overcame his tortured, fractious relationship with a domineering father who demanded his son pick up a practical trade.

Gilbert, then, is many things. It’s a riotous concert documentary and a compassionate inquiry into the role of comedy, which, for Gottfried, is at once a release valve and a suit of armour. It’s also a self-reflexive critique of the role of a comedian that admires but doesn’t lionise Gottfried’s reputation as an unfiltered loose canon: a joke about Mackenzie Phillips and father-daughter incest is clearly drawn as a line in the sand, as are the 2011 Japanese tsunami tweets that almost sank Gottfried’s career.

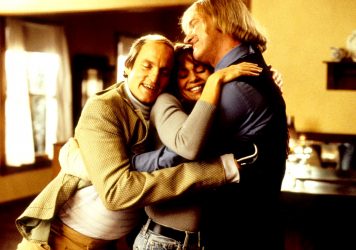

But Gilbert is, just as crucially, a love story between Gottfried and his family, including his wife Dara, a charming woman who can more than keep up with her husband’s breakneck quips and comes forth as both his critic and defender. This latter focus also extends, quite poignantly, to Gottfried’s tight-knit relationships with his sisters Karen and Arlene, whom he visits every day when at home in New York.

Gilbert is never more moving than when it veers away from its subject to concentrate instead on the older, multifaceted Arlene, who passed away in August 2017. Arlene saw street photography and, later, gospel-singing as personal, spirit-lifting forms of expression that were as equally vital as her brother’s comedy. Berkeley’s film quietly pulses with the knowledge that we all have our coping mechanisms, whether it be the soothing click of a camera-eye or the roaring, cathartic laughter of a full and reciprocative house.

Published 3 Nov 2017

Comic bio-docs are a hackneyed subgenre these days.

A hysterical treatise on comedy as profession and life-raft, with heart and honesty in all directions.

The filmmaking set-up is familiar but the insights — and comedy — are worth it.

The writer-stars of Mindhorn interview each other about their comic influences.

By Nick Chen

Kumail Nanjiani’s portrayal of a professional joke-teller is refreshingly honest and authentic.

By James Oddy

The Farrelly brothers’ reached their vulgar, freewheeling peak with this 1996 bowling comedy.