Greece’s Anima Syros festival provided a platform for a bright new generation of women animators.

A young woman is naked, her legs spread wide open on a sofa. Yet, whether it’s the noise from traffic outside or the unwanted attention of a neighbour, she just can’t seem to get comfortable enough to continue pleasuring herself. After a number of false starts and with her frustration mounting, the camera zooms in on her animated clitoris. As it sprouts a face and fangs, and the labia turn into wings, the whole thing morphs into a vagina-come-vampire bat, flutters into the air and sweeps down to devour the Peeping Tom trying to catch a glimpse from outside.

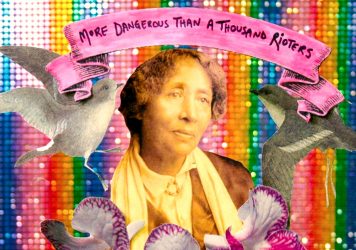

This scene from Cipka (Pussy) by Polish animator Renata Gąsiorowska is just one of a host of outrageous, disconcerting and downright hilarious moments that wowed audiences at Greece’s Anima Syros festival, created by a stellar cast of female animators. The wealth of talent on show and their confidence to take on personal and provocative subject matter – from masturbation to alcoholism and BDSM – is a proud indication that this bright new generation of female animators have balls.

But while the majority of students on most animation courses today are female and female animators are increasingly well-represented at short film festivals, only two woman have won Academy Awards for Best Animated Feature Film, Brenda Chapman for Brave in 2012 and Jennifer Lee for Frozen in 2013. So, what is stopping young talent progressing through the industry? LWLies sat down with an international group of female animators showing at Anima Syros to talk about how much progress has been made, the blocks that remain and what can be done to overcome them.

“Every year there’s just so much more content, the barriers to entry fall and it’s easier to get the software and start making animation, so that has helped encourage a big increase in female animators,” explains Aisha Madu from the Netherlands, director of Helpiman, a tragicomic tale about a man whose willingness to help others is not reciprocated when he himself needs a lifeline. “But the boys win all the awards and I’ve lost count how many times people thought Helpiman was made by a male director.”

Women were locked out of all but the most menial tasks at major animation studios like Disney until well into the 1950s. The ‘boys club’ dies hard, with women today still too often pushed towards design rather than story. But a lot has changed in the animation world, and many of the most creative voices work independently, well outside the big animation studios, on shorts made by small teams, like Tabook.

“We want to break taboos and open up the conversation around young women and sexuality,” explains Tünde Vollenbroek from The Netherlands, who produced the film, whose lead almost bursts with embarrassment when she tries to borrow a book on bondage from the library. “We hope the film gives women the courage not to care and forget the shame they felt during their teens.” Tabook sought out its target audience and was seen by half a million Dutch cinemagoers, before each screening of the latest Bridget Jones’ Diary, through a Pathé programme that supports short film by attaching it to blockbuster releases nationwide.

More people are watching animated shorts than ever before, mainly online, but creators still struggle immensely to get projects funded. “The form isn’t doing well anywhere, in the sense that it’s not supported, screened on television or respected in the way it once was,” argues Špela Čadež from Slovenia, who directed Nočna Ptica (Nighthawk), a psychedelic romp about a drunk-driving badger. “Everyone advises you to do a feature, but the imbalance there is obvious: it’s only male directors doing features. The very badly-financed stuff, like animated shorts, are left over for the crazy women like us. That leads to a high attrition rate as female animators can’t pay the bills and slowly but surely, they fall out of the industry.”

The group argue that funding priorities could change to support female animators make the jump to features. They would like animation schools to push more women towards directing, see women in leadership positions to inspire the next generation and develop mentoring and peer support networks, which is especially important for independent directors. But as such important steps in a director’s career, festivals need to change too. Women may be well-represented in programming, but when it comes to talks and panel events, men still dominate – and Aisha has become so used to be being the only person of colour at European festivals.

“There’s a long-held prejudice that women can’t make certain films, especially comedy,” explains Britt Raes from Belgium, who directed Catherine, a tragic tale of a crazy cat lady. “I think it’s really cool when I get a lot of guys telling me I made them laugh with this very pink, girlish character. So, I feel like we have come a long way and on some levels things have improved a lot. But there’s a danger that we’ll say, ‘Oh, it’s better now’ and stop trying. It’s not as bad as it used to be, but there’s still a huge amount to be done.”

For more info on this year’s festival visit animasyros.gr

Published 13 Oct 2017

By Matt Turner

The recent Edge of Frame Weekender showcased bold contemporary visions and rarely seen masterpieces.

By Eve Watling

2017 is shaping up to be an exceptional year for women behind the camera.

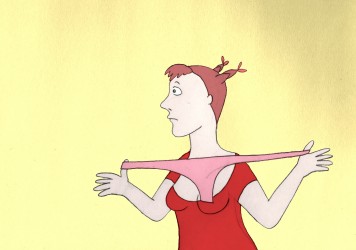

Check out this choice cut from director Signe Baumane’s brilliant The Teat Beat of Sex series.