The samurai’s armour is shining black like his betrayal. He has done all in his power to avoid the fate that was predicted in the forest over the way from Cobweb Castle. As the trees begin to walk towards his defences, his fear finally snaps his sanity in two. His eyes are starkly white, like the hundreds of arrows of his own men that soon switch allegiances and seek to take out this manic, flailing creature. The samurai still moves whilst pierced by the thin but deadly wooden weapons. He appears like a demonic entity, all the more terrifying as deep down we know that he is ultimately all too human.

When considering the monumental array of Akira Kurosawa’s cinema, a wealth of images stand out. Whether rain-soaked samurai battles or simply a man riding a child’s swing, Kurosawa created some of the form’s most celebrated scenes. Though his images were often breathtaking, few carry the same menace as the final moment of his formidable adaptation of William Shakespeare’s ‘Macbeth’, Throne of Blood. And it is thanks to the performer at the heart of this scene, Toshiro Mifune, that the image of the arrow-pierced warrior is so ingrained in our collective cinematic memory.

Though dramatically different in regards to the language of Shakespeare’s drama, Throne of Blood still remains true to the overall narrative structure. Eleventh-century Scotland is transposed to Feudal Japan and the film follows Washizu (Mifune) as the Macbeth figure. Riding back with Miki (Akira Kubo) after defeating the enemies of their leader, Lord Tsuzuki (Takamaru Sasaki), they come across an ominous spirit (Chieko Naniwa) who prophesises success for the pair in their future rising among the samurai ranks.

As the prophesies unfold, Washizu becomes greedy for power, driven by his wife, Asaji (Isuzu Yamada). Several bloody betrayals later, and Washizu sits at the head of Cobweb Castle. But how long will his reign last before the final prophesy of his fall comes true?

“Mifune’s performance is a perfect portrayal of crumbling confidence, a man who is desperation personified.”

Kurosawa marks his shift from the poetic language of the original play to his visual, movement-based drama by basing his film on the theatrical practices of Noh. Driven by an emphasis on movement and stylised gestures, the form is fitting for the tale of Macbeth, not least in its regular inclusion of supernatural elements and characters. In this sense, Mifune is well placed as the lead, with his physicality often driving his work with the director. It’s there in Yojimbo and Seven Samurai too but takes an unusual, sometimes terrifying turn in Throne of Blood.

We first see Mifune wild-eyed in the rain-drenched forest, an eerie place where the storms unusually leave the fog untouched. His movements are sharp and frantic from the off, as if every muscle in his body reacts instantly to the stimuli of the narrative world. Even when simply striding across a room, his rhythm conveys power and expressive purpose, especially as the character is increasingly forced to exert fear over all those around him. Men literally part like biblical tides when he moves between them, partly out of worry over his increasing lack of control, and partly because a sense of his cursed future.

His rage, even self-loathing, filters through to every look and action. Several times after his betrayals, he tries to wipe away the stain of guilt as if it’s a physical blemish upon his body. He almost flails as the ghosts of these betrayals begin to literally appear before his eyes. The lust for power ransacks his sanity and morality, resulting in a rising mania. Mifune’s performance is a perfect portrayal of crumbling confidence, a man who is desperation personified. It’s one of the most energetic performances of Shakespeare ever put on screen.

In his final scene, one of the great deaths in canonical cinema, Mifune is arresting and the raw energy of his performance reaches its peak. As the prophesy comes true and the trees seem to march out of the fog towards the castle, his own men turn on him, realising the danger of their leader’s madness. He flees through the barricades of the castle like a cornered animal trying to avoid his fate as dozens of arrows begin to find their mark. Kurosawa famously used real arrows for this scene, Mifune conveying where they should go via his movements. There’s a palpable, wild nervousness in this eyes, his terror being disturbingly real.

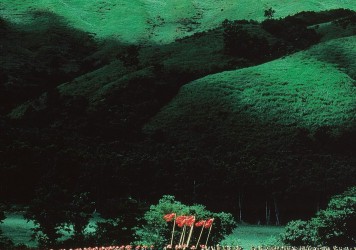

Ultimately, there is something animalistic about Mifune’s performance that marks it out as one of his rawest and most unnerving. His lumpy, shining armour renders him as a crazed invertebrate in human form, not unlike the centipede that acts as the insignia of his flag. Like an invertebrate, he continues to wriggle on when wounded until that final arrow finds its mark and his body crashes to the floor. A gulf opens as Mifune’s energy dissipates, the film deflated by his death and no longer able to continue without his insect rage to drive it.

Published 1 Apr 2020

By Amandas Ong

The Japanese master’s 1951 film Hakuchi is a celebration of humanity and its failings.

The Japanese director’s bleak and beautiful 1985 film returns to cinemas.

By Adam Scovell

The Swedish-born actor is at his transfixing best in Ingmar Bergman’s 1968 drama.