The Whitmans, the Tenenbaums and others lifted my spirits at a time when it seemed nothing could.

My childhood was measured in breakdowns. When I was eight, my mum nearly died having a liver tumour removed. I was 13 when I started seeing a psychiatrist, and 14 when my parents got divorced. I didn’t see my dad very much after he left, and my mental health rapidly deteriorated as our family imploded. I was terminally unwell – everything was greyscale, all sound reduced to the dull thud of a tension headache.

Film was my escape, my way of leaving the skin I hated and fleeing to someplace else. When I think back on being a teenager with the world corroding around me, I remember watching Wes Anderson films. I could identify with his characters’ desperate melancholy, but more than that, those family portraits helped me to heal when I needed it the most.

Be it the literal (the Tenenbaums and the Whitmans) or found (the staff of the Grand Budapest Hotel or the crew of the Belafonte), Anderson’s families are rarely happy, but I understand now that all the best stories come out of dark places. His films confront difficult themes like death and mental illness with raw frankness at odds with his carefully stylised scenery, and parental and sibling relationships are integral to these stories.

Everything about Anderson’s films reminds me of home – strange, given that I grew up on a sink estate in the north of England, in a house too small for its four occupants and the handful of animals also residing there at any given time. Even so, I hear it in his soundtracks, remembering The Rolling Stones blasting from Dad’s hifi and Simon & Garfunkel warbling in the kitchen while Mum made dinner, the music he uses transporting me to a time and place. Most of all, I see it in Anderson’s families – groups of oddballs and misfits just like the one I belong to.

Consider Gene Hackman’s patriarch in The Royal Tenenbaums. Royal is absent and neglectful like the father I had, but he at least made some (belated, misguided) effort to connect with his children, like the father I wished I’d had. Similar to Mr Tenenbaum, my father never really wanted to be a father, and only took a paternal interest when one of us showed some aptitude for the things that he enjoyed: camping, rock music, church. I was the Richie of my family, the only one invited on excursions, my father’s daughter until he moved out. A failed child prodigy wrestling with the pain of growing up unremarkable, suicidal thoughts threatening to become actions.

I always understand Eli Cash’s desperate yearning to belong when he says, “I always wanted to be a Tenenbaum,” but it wasn’t until I gained the perspective of time that I understood Royal Tenenbaum’s reply: “Me too, me too.” Those four words revealed the frailty of fatherhood – he was ultimately a weak man, trying too late to right his wrongs. His children turned out just fine without him, or at least, as fine as you can be when you realise the painful truth: your parents are human, as flawed and limited as everyone else. Children build them up to be so much more inside their head.

In The Darjeeling Limited’s Whitman brothers I saw my relationship with my own siblings: touching from a distance, bickering between ourselves. They didn’t understand my mental illness; I didn’t understand their autism. In the middle of an almost slapstick fight, an upset Francis Whitman shouts accusingly: “You don’t love me!” to which his brothers Peter and Jack reply “Yes I do!” and “I love you too, but I’m gonna mace you in the face!”

That’s how I feel about my siblings: I love them, but sometimes I want to mace them in the face. We’ve only come close to understanding each other while leading entirely separate lives. Like the Whitmans, I think distance helped our relationship – it enabled us to gain some much needed breathing space. We still fight. When I call Mum, I can often hear her refereeing arguments in the background between my brother and sister (who are now 26 and 22). When I go home we still needle at each other in the way only brothers and sisters can. We don’t talk about Dad, or how difficult I made life when we were growing up, but I feel it. We’re bound by our shared experience and all the pain that went with it.

So much of Anderson’s vision revolves around the smallest details in the worlds he creates, and how these turn a character sketch into a human being. Chas Tenenbaum’s Dalmatian mice, Suzy Bishop’s binoculars – those tiny particulars reflected to me the minutiae of my own life, and it’s those things I find myself returning to, time and time again. I picture Dad’s heavy metal CDs, my sister’s pet snails, my brother’s collection of Lego mini-figures. You have those micro-memories too, singular as your fingerprints, making up the detritus in a portrait of your home. Anderson’s way of capturing these moments taught me to cling to the small memories; those tiny, happy parts of big, sad situations.

At their heart, Anderson’s films are character studies about odd people in peculiar circumstances. This is always how I saw my own family, and I saw myself in Richie Tenenbaum’s suicidal inertia and Max Fischer’s awkward navigation of adolescence. In Anderson’s characters, everyone’s neuroses are not only put on display but seem to be celebrated – it’s like Mrs Fox says, referring to her husband: “We’re all different. Especially him. But there’s something kind of fantastic about that, isn’t there?” Those literal or found family units make tragedy easier to survive. His characters made me feel less self-conscious about my own strangeness, and lifted my spirits at a time when I thought nothing ever could or would.

In Anderson’s oddball families, I came to appreciate what was left of my own, and in their neat endings, I found the closure I needed.

Published 18 Mar 2017

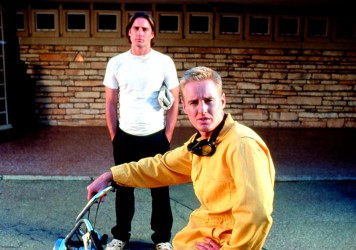

From Bottle Rocket to The Grand Budapest Hotel, we rank the American director’s nine features.

Wes Anderson’s brilliant debut, which turns 20 this month, channels the youthful spirit of Mean Streets.

Watching Gus Van Sant’s 1991 film was like an emotional awakening – a guiding light through sexual fog.