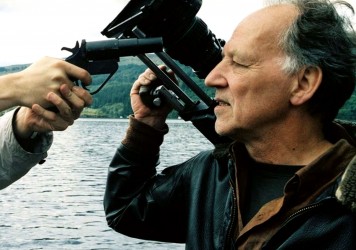

“That’s El Tunche, the evil spirit.” Welcome to the jungle – specifically the Inkaterra Reserve in Peru, Madre de Díos river, Amazon Basin. Things here are strange by nature; giant snails, night monkeys, violent bushmaster snakes. Turn your back and a tarantula might creep into your shadow. It’s a mythical place, with tribes hidden between the dense rainforest and impassable jungle. The climate is the same that Werner Herzog endured during his tumultuous production of Fitzcarraldo 36 years ago, and the same he will share with 48 emerging filmmakers over the next two weeks. This is my personal account, for what it’s worth.

Day 0

Being from the Baltic north of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, I decide to arrive early to acclimatise. Three days in Lima then the jungle town of Puerto Maldonado to meet up with the other workshoppers and begin our journey. The first wave arrive and we take a motorised canoe up the river to base camp. Vines drape overhead from 300-year-old Lapuna trees, bushes rustle with critters and a thick wave of humidity dulls the senses. Wave two arrives with whispers that Werner may appear tonight. He doesn’t. He just got back from Japan and needs rest. He’ll see us tomorrow, 05:30 sharp.

Day 1

Herzog arrives and takes the time to shake every hand. He informs us we’ll all make a film, and that the theme is ‘fever dreams in the jungle’. The first two days will be location scouting and casting portfolios. A herculean effort from host staff Black Factory Cinema has secured nine locations and more than 200 locals to appear in the films. We visit the native Ese Ejas tribe, are greeted by their chief then given a demonstration of tribal customs. It’s like a BBC documentary, except everyone has Direct TV. Then we’re back to base so the boss can watch Bayern Munich get knocked out of the Champions League.

Day 2

More location scouting – first up is the idyllic Lake Sandoval and then its back to Puerto Maldonado. Sandoval is a one hour walk into the forest but Herzog manages it no problem – not bad for a 75-year-old. In town I have a lead of my own and want to get going – I ask if I can film the next day; the organisers tell me I have to okay it with Werner. I explain to him my plan before delving into the ideas for my film. He stops me. “So long as it’s not softcore pornography, I don’t care.”

Day 3

There’s a routine now and people are beginning to get to the work. Two things about the jungle: it’s always damp, and it’s never quiet. Sleep is a byproduct of exhaustion. Tonight I’m staying in town so I can film at sunset on my secret lagoon – the boats can’t navigate the river after dark. My two non-professional actors and I go piranha fishing on then head back to town to fry and eat them. Aside from the guts, you eat the full fish, so I enjoy my first taste of fried piranha heads.

Day 4

Back at base camp, I’m isolated from the group today as they’re beginning while I’m already going. In my head, if I finish faster than others, I’ll get more feedback from Herzog (something I’ll later live to regret). I spend the day in the canopy above the jungle trying to film Howler monkeys. Regular day in the jungle.

Day 5

On the fifth day, an epiphany: Werner Herzog isn’t Werner Herzog – he’s Werner Herzog. He’s the mythical filmmaker. It’s a performance. You have to break down the performance or all you’ll get is weird and wonderful sayings, such as “It is the job of the filmmaker to jump out of the window into the boat even if he has no confidence there is water beneath it.” When you get past the guard the guy is remarkably attentive. He focuses on what you want, tells you what you need to hear.

Day 6

Another day of filming; I’m between the town and the jungle. The characters are in the town, but I came to the jungle to make a film in the jungle. My lead actor is a baker whose story is one of tragedy and triumph. Her husband was a guide who drowned in the river, leaving her with two small children. She worked hard, she overcame her grief, she found love again. I film in the bakery where the ladies working there tell it straight. “You all work so hard! It’s amazing,” I say. “You forgot to say we’re beautiful, also,” is their response. Tomorrow I hope to wrap up filming.

Day 7

One of the very first things Herzog told the group was that dysentery was a badge of honour. He is an immersive filmmaker – his stories take time, in exotic locations with clashes against local authorities. He is a rebel with a hobo heart. My efforts to emulate this in some way left me bed ridden today with exploding insides. It’s not sexy but it’s the truth. I tell him later and he laughs. “Good!”

Day 8

Today was my most exciting filming day. I began with two Machiguenga, filming a hunting demonstration and conversation. Machiguenga cannot be translated, even in Inkaterra – I’ll need to find an expert somewhere else. Herzog told me not to go – he wants us to finish, not to complicate the process, but I knew if it was him he would’ve done the exact same thing. Then I caught whatever boat I could to Puerto to get the last shots with my actors. It all goes to plan and I’m relieved – now I’ve got to edit a lot of footage in two languages I can’t speak.

Day 9

For the first time I get distance from the work and begin to think on the experience. My fellow filmmakers have come from across the world – the UK and US, Kosovo, Colombia, Australia and Singapore. Quite unbelievably there’s not a bad egg amongst the lot. Everyone is smart, funny and on the same page. Maybe it’s the heat, but we’re not a group of filmmakers, we’re a family. A team. Everyone is there for each other with the mad German in the middle steering us all to project completion. This is truly once in a lifetime.

Day 10

Every night we gather for what Werner calls ‘campfire’, where he answers questions and tells stories. He’s talked about everything save for eating his boot (why did we never ask him about that?) but the most interesting things he says are when he gets sentimental about life. He’s old, married and in love. He’s done it all and thirsts for more. Two things stick in mind – first, he talks often about how he’s just here to help the next generation take over. Werner Herzog wants to inspire the next generation of Werner Herzog’s. Second is his philosophy on taking a journey – he once walked the border of Germany in political protest, but now says he would only take such a journey to ask a woman to marry him. Werner Herzog is oddly sentimental – both mad scientist and romantic.

Day 11

I complete my film and show it to the group and Herzog. “I don’t like this new age stuff.” Well shit, Herzog didn’t like my film. In fact, of the 48, mine is the one he would specifically indicate his dislike for (thanks to Samir for pointing this out). I don’t really care. It’s my work; some people like it, other don’t. You don’t attempt to emulate Terrence Malick without expecting some backlash. If I can’t be Herzog’s favourite, there’s a badge of honour in being his least favourite. I like to think he would agree.

Day 12

We spend the last day running the gauntlet of 45 films, about three or four hours of cinema. The work is a high quality of filmmaking considering we’re here with what we have in a place that is not made for it. Some of the films are breathtaking – brave, weird, personal. Herzog says it’s inspiring, I think he’s right. We end the last day with a jungle party: bonfires, music, pisco sours and a happy-drunk Herzog. It’s been a whirlwind, an adventure – a fever dream in the jungle.

I went to the jungle for a once in a lifetime experience where I hoped to learn from a master filmmaker, but won the lottery by sharing the experience with such a remarkable group of people. Herzog – an optimist who believes humanity is doomed – inspired. I could say every budding filmmaker should attend a workshop in the Amazon basin with a cinematic legend but that’s a given – so instead maybe go on a journey on foot, or jump out of a window even when uncertain of safety. Chase your fever dreams wherever they lead you – he opened the door so we can follow.

Published 10 Jun 2018

Two writers make their case for the most eccentric moment in the director’s career.

Werner Herzog’s 1972 masterpiece returns to the big screen, which is a cause for major celebration.

By Tim Cooke

Encounters at the End of the World features one of the great existential moments in modern cinema.