Although released in 1976, Matt Cimber’s The Witch Who Came from The Sea gained widespread attention in 1984 when the Director of Public Prosecution put it on the ‘Video Nasties’ list, censoring and banning it in the UK from the public. That being said, unlike most of the other films of its ilk that made the list, The Witch Who Came from The Sea has very little gore in it. While the film does have explicit nudity, it shrinks into oblivion when combined with the excruciatingly horrifying and realistic themes it delves into.

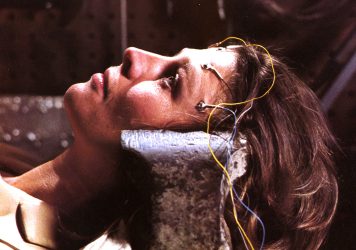

Fresh from her well-received role as Anne Frank, Millie Perkins plays Molly, a single woman who adoringly dotes on her two nephews. She paints a romanticized memory of her sailor father, idolizing him to be just as noble as the celebrities they admire on television, before ultimately dying at sea. Her sister Cathy (Vanessa Brown) gently reminds Molly that this is not exactly what happened, with the reality being that their father repeatedly inflicted sexual abuse on her, which we discover through sickening flashbacks and hallucinations.

In what turns out to be a unique way of resolving her frustrations from her traumatic past, Molly begins seducing men that society has deemed heroic (Hollywood stars, sports figures) and having her way with them before castrating and killing them, only to wake up with little to no recollection of what had happened. As we weave throughout Molly’s tragic tale, her blackouts begin to feel more real – a self-realization of her own mental illness.

While some of its ‘nasty’ contemporaries such as I Spit on Your Grave had a much more black and white rape-and-revenge approach to exploitation horror, The Witch Who Came from The Sea is distinctive for several reasons. If we’re being honest, in most cases exploitation flicks are light on the plot. The gore and nudity are essential to a ‘nasty’ and usually serve the sole purpose of titillating their audience. In the case of The Witch Who Came from The Sea, the film features not only a Freudian lens, but is riddled with mythological symbolism. Further, Molly’s harrowing past and nurturing disposition evoke sympathy and pity – emotions that the viewer misses out on in regular grindhouse entries.

Robert Thom’s script also makes television a central piece of the film, particularly its manipulative power; an incredibly fitting theme for the time. Molly’s murders are triggered by commercials and conversations about celebrities, as she’s immersed in the television’s power of idealizing masculinity in society. This mirrors her fractured memories of watching TV as a child to tune out her father’s abuse – resulting in her romanticized view of TV’s finest icons. At one point she tells one of her suitors, “television makes people so much kinder, doesn’t it?” Molly openly idolizes these picture-perfect men after seeing them on TV, parallel to her idealized view of her abusive father. Once she seduces them and they turn out to be subpar, she kills them, taking their manhood in the process.

Thom’s clever references to classical mythology in the script, along with constant metaphorical references to the sea also add a poetic element separating The Witch Who Came from The Sea from its generic ‘nasty’ brethren. We find out that the sea itself is a euphemistic term Molly’s father used to describe the sexual abuse, telling her they’ll get “lost at sea” together. At another point, we see Molly gazing intently at a reproduction of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, with one of her male admirers explaining the myth to go with it. She learns Venus’ “father was a god” who got thrown into the sea and castrated, “knocking up the sea and Venus was the kid.”

It is with this painting that Thom wraps a neat bow on the carnage that surrounds the movie, tying the theme of emasculation that so very evidently runs throughout the film. It is also to be noted that classical mythology had very gendered monsters, many of which were female. Sirens, for example, were described as birds with the heads of women, luring sailors close to shore before killing them. The overt sexuality that Molly possesses is what makes her very desirable to her suitors – yet lethal. This archetype of the deadly female would prove to dominate horror cinema in years to come.

The key theme of disillusioning oneself between fantasy and reality, particularly through media and television, still rings true to this day, in a time we’d rather be staring at a screen than facing our own ugliest realities. A tragic character study on the aftermath of childhood abuse and an examination of celebrity worship was unfortunately marketed as a horror film and wrongfully dismissed. At the end of the day, The Witch Who Came from The Sea is not a cinematic masterpiece by any means, but an intelligent film that deserves more credit than the genre it was placed in and worth a watch as a little-known psycho-slasher gem of the late ’70s.

Published 27 Jan 2019

By Anton Bitel

On the envelope-pushing effects work of Sam Raimi’s hand-tooled gorefest, set for re-release this Halloween.

By Grace Lee

Grace Lee searches for meaning amid the so-called monstrosity of this superlative 2017 horror.

Before Charlie Brooker’s dark social satire, there was Donald Cammell’s technophobic sci-fi.