Upon its release in 1990, Volker Schlöndorff’s film adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ was widely dismissed by critics. These days, it’s a largely forgotten relic, difficult to track down even in the age of limitless streaming and overshadowed by the hugely successful Hulu series. As the film’s 30th anniversary approaches, it’s tempting to retrace the steps of this doomed retelling, exploring where it went wrong and how the very same source material was used to create one of the most well-regarded TV shows in recent memory.

So, why didn’t it connect with audiences? Well, context is key, and it’s easy to see how this gruesome tale would catch on in the current global climate. Three decades later, we live in an era of increasingly blatant authoritarianism. Audiences turn to dystopian storytelling because, at their most affecting, they can work through society’s failings, serve as a hopeful reminder of the resilience of the human will, help to navigate the turbulent waters of social change, or (at the very least) distract us with the sheer entertainment factor a good thrill can provide.

But that certainly isn’t anything new. Oppression wasn’t breathed into existence somewhere between 1990 and 2017, when the series premiered. Hell, just a handful of years prior, critics and audiences both were much kinder to Michael Radford’s strikingly bleak adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four, even though George Orwell’s nightmarish portrait of the easily imagined tyrannical future was clearly a direct influence on Atwood’s novel.

Much of the film’s failings land on the shoulders of its shoddily assembled production team. Schlöndorff and screenwriter Harold Pinter had absolutely no business telling this story. Throughout its runtime, it becomes increasingly clear that there were no women even given the opportunity to offer input at any step of the process. The Handmaid’s Tale suffers from a complete misunderstanding of – and wilful apathy towards – the female perspective. Even Offred’s internal monologue was entirely gutted, and the audience is left to work out on their own who she is as a central character, rather than being shown why we’re meant to identify with her plight.

Cinecom Pictures were trying to cash in on a book-of-the-moment with an adaptation that lacked the care and attention necessary for biting satire – and audiences saw right through it. A complete commercial failure, the film didn’t make back half of its budget. Filmgoers were too busy seeing House Party or Joe Versus the Volcano or, more likely, The Hunt for Red October for a third time. It’s no surprise that the studio would shut its doors after filing for bankruptcy the following year, a swift fall from its mid-’80s heyday.

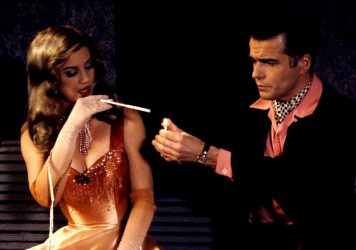

Simply put, The Handmaid’s Tale is just plain lazy. Schlöndorff squanders his star cast (Natasha Richardson, Faye Dunaway, Robert Duvall) through a dry, almost surgical approach that’s devoid of emotion. The film is more concerned with delivering cheap thrills than a nuanced dissection of gender politics, turning an inspired fable into little more than drugstore pulp. The lifeless script ignores the why of it all. It doesn’t help that the overbearing score seems, at times, to mimic that of The Terminator. What’s worse is that it doesn’t even clear the incredibly low bar it sets for itself. Neutered to the point of boredom, the result is the worst of both camps, failing to flourish on either an entertainment or insightful level.

Sure, Atwood’s allegory shines through at times, as nuggets of perception shimmer from beneath the muck and mire. In a manoeuvre that was surely born more of necessity than of ingenuity, its setting feels a bit more firmly tethered to the present than the series, due in part to its aesthetic minimalism. It isn’t difficult to accept this doomsday prophecy, as its world seems only a few shades away from our own, making the graphic scenes all the more uncomfortable.

However, the tonal heft is always undercut by how little it seems to think of itself. Schlöndorff never takes the story seriously, and so the murky atmosphere disrupts any chance it has at landing its point. The Hulu series arguably falls into the horror genre, whereas this adaptation can’t quite decide what tone it’s going for. At times it’s almost twee (hopeful, even), forfeiting the moments that should otherwise be excruciating to watch. There’s absolutely no urgency whatsoever, so the stakes feel so tediously low, which is a surefire way to smother a dystopian narrative.

Perhaps this iteration of Atwood’s novel was never going to land. This isn’t the kind of parable that can be neatly wrapped up in 109 minutes and, more importantly, this awkward film is a misguided attempt that never does the source material any justice. Schlöndorff doesn’t touch on any of the novel’s deeper implications until the final scenes, and, even then, they are hurriedly thrown together and only examined on a slapdash, surface level.

The fact that the series would go on to fully flesh out this world in a way that would even surpass the book makes this adaptation all the more disappointing in hindsight. Ultimately, 1990’s The Handmaid’s Tale misses nearly all of the story’s potency, feeling more like a Sparknotes recap of the novel, without any of the thematic insights.

Published 8 Feb 2020

By Lewis Gordon

The hit dystopian series isn’t just about violence against women.

By Alex Denney

The original cast and crew discuss the making of this short-lived follow-up to Twin Peaks.

By Nadine Smith

Like Philip K Dick’s replicants, Kurt Russell’s steely-eyed space marine asks what it means to be human.