At a certain point in most every Marx Brothers film, all the building chaos and thinly spread drama suddenly comes to a stop – Chico sits down at a piano and Harpo picks up a harp and, for a few minutes, they just play. This might seem strange, especially in 1931’s Monkey Business when it comes a scene or two before the climax, and maybe it’s not surprising that their most acclaimed film is one of the few without a musical interlude. But Jonathan Richman, one of the first to recognise the genius of The Velvet Underground, thought they were worth dedicating a whole song to. In ‘When Harpo Played his Harp’ he asks the most important question: “if someone else can do it, how come nobody does?”

Every few months, someone, usually from outside of the online film space, will post about sex scenes. They will complain of their gratuity and how they do nothing to further the plot, as if projecting their disapproval to an uncomfortable parent sitting next to them. Then, naturally, everyone will dunk on them. The counter arguments — that thinking of art only in terms of functionality mirrors capitalism’s belief that there is only value in productivity — almost don’t bear repeating. But of course they will be the next time someone makes a similar post. It happened while I was writing this. It always loops back around, the arguments never go any further, few think to ask that if sex scenes, or any other type of scene, don’t need to serve the plot, do they need to serve anything at all?

In cinema’s earliest days, when it was just a carnival attraction, its appeal was partly technological. There was a thrill in images moving, so those images could exist for their own sake. The pleasure was not so much in looking as it was in seeing (whether a foreign country, a dance or a kiss).

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

This isn’t to say that early cinema was entirely base. There was, in fact, great artistic beauty (Hong Sang-soo included the Lumières 1895 film Boat Leaving the Port on his Sight & Sound list of the ten greatest films ever made) but the medium’s complexity, in terms of narratives and special effects, hadn’t yet grown to obscure the power it has in and of itself.

For all their extravagance, Hollywood’s large sets, stylised performances and formalised genres often felt like an especially thin layer. Even in the mystery film, a genre that, in theory, is the most concerned with narrative. Most of the time the plots made no sense; they were impossible to follow because they weren’t meant to be. They created momentum between the scenes, the moments that we actually engaged with. The best example being The Big Sleep, a film that is as pleasurable as it is incoherent; even the author of the original novel didn’t understand the ending. Howard Hawks’ film of sparking chemistry and straight-forward beauty “made us aware”, Pauline Kael wrote in Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang, “how little we often had cared about the ridiculously complicated plots”.

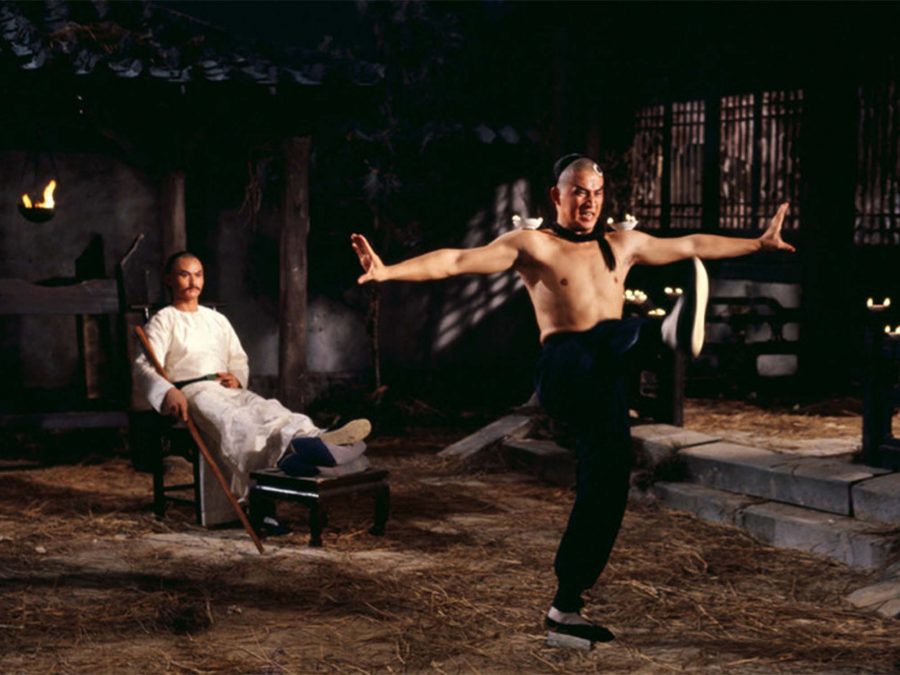

Few understood this as well as the people making martial arts movies in Hong Kong through the ’70s and ’80s. The action sequences were sometimes shot over months, while plots were generally contrived later and filmed quickly after the real work was done. The thrill of seeing bodies in motion – an intricate and artful evolution of the Edison films of athletics and weightlifting – was the entire point. That’s why they so often end seconds, frames after the last enemy is defeated.

Lau Kar-leung, one of the geniuses of their system, made a joke of this in his 1979 masterpiece Dirty Ho: once the lower class Ho has escorted Wang, a disguised prince (a perfect excuse for a fight scene where he puppets someone else’s body to keep his identity hidden) to the Emperor’s palace, before finding out who is next to be crowned, the prince grabs our hero and throws him out, and us along with him. It simply does not matter. The film doesn’t even last long enough for Ho to hit the ground; it ends in motion.

But something has changed since then. It’s not just that action movies, to stay with his particularly clear example of the pleasures of seeing, are now so over-edited that the behind the scenes clip of Tom Cruise breaking his foot is far more exciting and visceral than the scene that footage ended up in. That lost sense of reality also comes from the medium itself, which has moved from physical to digital: the images are no longer photochemical reflections of something physical but collections of endlessly malleable pixels.

The artifice of Old Hollywood always pointed back to reality: the fake sets pointed to the craft of building them and the unnatural performances pointed to the much-loved stars. But digital artifice points only deeper into itself; even that which looks the most real, we all know, is likely enhanced, if not created wholecloth by some impossibly complex computer software. In the definitive digital meta-film, James Cameron’s Avatar, the CG world of Pandora seems so profoundly real to the audience-insert main character – enhanced, no doubt, by the cutting edge 3D – that it starts to feel more real, more all-consuming, than his own life. Eventually he dissolves into it, his soul transferred to another reality that J. Hoberman describes in Films After Film as: “unbearably distant, yet overwhelmingly close.”

But this is only the most commercial and inaccessible end of the digital revolution on which Agnès Varda’s 2000 documentary The Gleaners & I sits opposite. On her small, consumer-grade camera, Varda collects footage of abandoned paintings, surplus potatoes and the people society has left behind, but not in a pointed way. Her film is like a digital scrapbook, she only follows her intuition, and, in doing so, transforms the passive pleasure of seeing into something active: a shared act of discovery. She finds a new beauty with clear echoes of Lumière films. Maybe this promise for the digital age has been left most unfulfilled, but if Varda’s film shows us anything, it’s that that which has been abandoned is only waiting to be re-discovered.

Published 27 Sep 2023