On training manoeuvres in the bayou, a group of Louisiana National Guardsmen lose their way and take boats from the local Cajun hunters without their permission. When one of the amateur soldiers fires blanks at the angered natives as a “joke” they retaliate with lethal force, plunging the hapless weekend warriors into a situation of genuine guerrilla warfare.

Originally released in September 1981, Southern Comfort was the last film in director Walter Hill’s early run of cult action classics before the box-office success of 1982’s 48 Hrs catapulted him into the mainstream (with somewhat mixed results). A gifted screenwriter as well as director, Hill’s first major success was his script for Sam Peckinpah’s The Getaway. Like Peckinpah, Hill’s work frequently both celebrates and critiques masculinity in crisis, and Southern Comfort is no exception, combining a violent surface with a more thoughtful dissection of conflict and survival.

We first meet the protagonists squabbling among themselves as they prepare for their exercise. Discipline is poor, with passive-aggressive teasing taking the place of camaraderie. Outsider Hardin (Powers Boothe), who has been transferred from El Paso, sums up the group as “Louisiana versions of the same dumb rednecks I’ve been around my whole life.” The boats they steal are found at a makeshift settlement littered with the bodies of slaughtered animals – imagery that recurs throughout the film. The symbolism is not subtle: most of these men are doomed, hopelessly out of their depth once reality intrudes on their macho fantasies.

Alongside the easy-going, self-aware Spencer (Keith Carradine), Hardin is the closest thing the film has to a hero. Though handy with a knife, Hardin’s character subverts many of the cliches expected from the role. He is intelligent, a professional chemical engineer, faithful to his wife, and scornful of the toxic posturing that surrounds him. These attributes never undermine his survival skills or integrity, with the film emphasising that brains are as valuable as brawn, with blind brutality no substitute for rational judgement. However, even Hardin is not infallible; shrouded in the symbolic fog, his baser instincts rise to the surface when facing the bullying Reece (Fred Ward).

“Southern Comfort stands as both a superb thriller and a sly commentary on male violence, nationality, and warfare.”

With its period setting, ill-prepared troops, hostile terrain, and guerrilla ‘enemy’, Southern Comfort has often been interpreted as a damning allegory of the Vietnam War. The soldiers are lost in the swamps, both literally and metaphorically, poorly equipped and sinking ever deeper into unknown territory. They are dismissively ignorant of the French-speaking natives, understanding neither their language or culture. Their bungled raid on a suspect hunting lodge nets only a defenceless one-armed trapper (Brion James).

They beat him rather than question him, and troubled recruit Bowden (Carlos Brown) destroys his shack in an act of entirely unnecessary, self-defeating vengeance, obliterating supplies they could have used as well as punishing a man whose guilt has not actually been established. The unfortunate Sergeant Casper (Les Lannom) could be seen as representing the naive hawks of the US political establishment. Thrust into command by unforeseen events, Casper can only quote from training manuals and threaten his men with increasingly irrelevant court-martials, unable to adapt to reality or to maintain authority as events spin out of his control.

Hill himself has always remained tight-lipped as to whether the film was intended as a comment on Vietnam. Certainly, the film withstands more than just one interpretation. Its own trailer compares it to John Boorman’s Deliverance, with which it shares themes of survival and the countryside ‘fighting back’ against outsiders.

Unlike Deliverance, however, the locals of Southern Comfort are not portrayed as inbred villains. They are shown to have their own culture and dignity despite the harsh environment, and they are not stupid – they understand English, while the soldiers can barely interpret their French. They are not the initial aggressors, but when roused they prove themselves to be far more resourceful, ruthless, and cunning than the National Guardsmen. Although they are their fellow Americans, the soldiers consider the Cajuns to be alien and inferior, raising pertinent questions as to who really ‘owns’ a nationality, and the costs of a society that fails to tolerate and respect difference.

Southern Comfort wears its concerns deceptively lightly, never labouring them at the expense of tension and momentum. Hill’s film is characteristically economical and spare, bolstered by strong performances and by Andrew Laszlo’s pungent photography, capturing the claustrophobia of the endless grey-green swamps. Ry Cooder’s eerily calm, stealthy score adds immeasurable atmosphere, its droning guitar and Chinese flute mingling with the bayou’s natural sounds, as if the landscape itself were stalking the characters. Building to a hair-raising climax, the film stands as both a superb thriller and a sly commentary on male violence, nationality, and warfare.

Published 21 Sep 2021

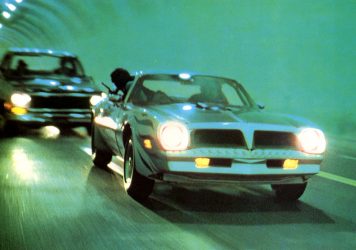

Walter Hill’s cult film is full of intense car chases and silent antiheroes.

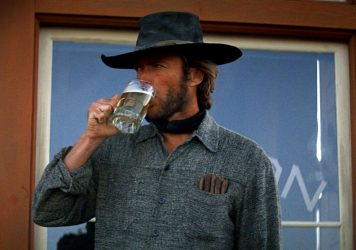

This controversial 1973 western ranks among the director’s finest works.

Alan J Pakula’s prescient 1974 political thriller sees Warren Beatty infiltrate a shady organisation.