You’d be forgiven for not knowing Disclosure had been released – I only stumbled upon it between Noah Centineo romcoms and true-crime docs on Netflix. Why would the streaming giant purchase a documentary about trans* representation? Perhaps they feel guilty for cancelling the Wachowskis’ Sense8, one of surprisingly few trans*-produced media the documentary shows. Still, it’s great to see Sam Feder, director of Boy I Am and Kate Bornstein is a Queer and Pleasant Danger, given a mainstream platform.

Disclosure is a great conversation starter, and the range of trans* talking heads is itself an achievement. If anyone doubts its relevance today, see the naïveté of Halle Berry wanting to play a trans* man (it’s been 18 years since her Oscar win) or the damaging comments by JK Rowling on Twitter. Hopefully they’ll watch Jen Richards or Laverne Cox tearfully recall the impact insensitivity has on trans* people’s self-perception.

I hope to elaborate on Disclosure’s examples so you know what to explore next. I’ve written on Lukas Dhont’s Girl and representations of gender construction for this publication. More importantly, I’ve been hurt by bad representation and, having appeared on the BBC’s University Challenge and suffered abuse, I understand the importance of improving public perception to make transitioning easier. As Cox says, we simply need “more”.

Disclosure is decidedly US-centric. This isn’t a problem as it doesn’t claim to cover universal experience. Richards’s reflection on a dad’s pride in his trans* kid and her realisation her own mum doesn’t see her that way is heart-breaking. People need to see support – the stream of clips reveals the shocking frequency of trans* characters dying on screen. Media influences people undergoing transition, revealing how perceptions of trans* lives form.

“When we watch trans* bodies, we shouldn’t be aware of their transness. We should all simply be allowed to be.”

Looking at international media offers more positive trans* representation. Disclosure briefly shows Daniela Vega in A Fantastic Woman and Belgian drama Ma Vie En Rose. But films like Céline Sciamma’s Tomboy should be celebrated for showing the importance of supporting a child’s identity exploration. Similarly, Fred Zinnemann’s The Member of the Wedding is an American masterpiece which has fallen into obscurity. Trans* historians like Susan Stryker bring light to those forgotten stories – her ‘Transgender History’ is an accessible overview of contexts within which the images in Disclosure were created.

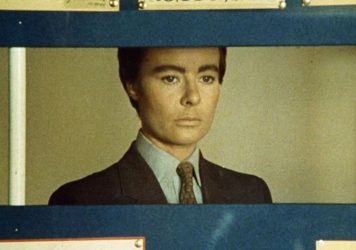

We mustn’t look past the horror trope of the trans* villain in this history, from Hitchcock’s Psycho through Dressed to Kill and The Silence of the Lambs. In Men, Women and Chainsaws, Carol Clover claims these films create a gendered binary between the camera’s masculine ‘assaultive gaze’ and the viewer’s feminine ‘reactive gaze’. Its influence has percolated into supposedly positive films – think of the scene in Girl when Lara cuts off her ‘penis’. The camera follows her, watching from behind, just as the point-of-view shot in the opening of Halloween aligns us with the murderer.

Girl must be condemned for portraying this life-threatening act which could influence dysphoric people. Netflix delayed its American release to consult GLAAD in creating a website for people affected. Dhont’s film uses an extreme scenario to force cis audiences to empathise. It doesn’t empower trans* viewers. Showing trans* characters’ genitals justifies the investigation of how trans* bodies are sexed. We don’t leave that curiosity behind – voyeurism isn’t worn like 3D glasses. But we lack cinematic omniscience outside, so knowledge is gained by verbal or physical force.

In Boys Don’t Cry, Brandon’s trousers are removed by two men to reveal Hilary Swank’s vagina. Jack Halberstam claims in his book ‘In a Queer Time and Place’ that we stop looking with Brandon and look at him. Gazing does cissexist violence to Brandon as his male gender becomes an illusion. As in The Crying Game, genital exposure is narrative pleasure – the mystery genre’s thrill of revelation. Questions we’ve been trained to ask – is he trans*? has she had surgery? – show we’ve internalised cinema’s transphobia.

Disclosure shows how trans* people feel watching these scenes. If we are supposed to gain pleasure by a character’s failure to ‘pass’, for a trans* person it’s devastating. Micha Cárdenas discusses this in ‘Shifting Futures’. When someone modulates their appearance to survive, what Cárdenas calls “shifting”, their value is determined by the perceiver. By contrast, Cáel Keegan’s book on the Wachowskis argues their films like The Matrix are trans*-positive because gender is defined within the film’s aesthetic instead of the outside world’s constructed binary. No one needs to ‘shift’ because there’s no gender binary.

At the end of her 1975 essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, Laura Mulvey called for the negation of gazing through avant-garde techniques. I don’t believe this is how trans* voices should be heard. Rather, we need a counter-cinema within the mainstream, like the Wachowskis have created. When we watch trans* bodies, we shouldn’t be aware of their transness. We should all simply be allowed to be. Wouldn’t that be nice?

Published 11 Jul 2020

How the language we use to talk about art which explores subjects of gender and identity can evolve.

Findings from a rare public screening of John Dexter’s I Want What I Want.

From Alfred Hitchcock to Fritz Lang, the process of creating women has long been an obsession of cinema’s greatest male creators.