Marred by production issues and a slew of rewrites and reshoots, 2002’s Halloween: Resurrection never stood a chance. Widely derided as yet another subpar addition to a franchise that failed to capture the essence of John Carpenter’s genre-defining 1978 slasher, Rick Rosenthal’s film is best remembered for its clunky dialogue, laughably pitting Busta Rhymes against the indomitable Michael Myers, and an anticlimactic ending to Laurie Strode’s initial arc. Yet despite its flaws though, Resurrection is arguably the most innovative film in the entire series.

A lot of credit must go to screenwriter Larry Brand, whose ambitious, somewhat prophetic vision tapped into the public’s emerging obsession with reality television. At the time, shows like Big Brother, The Real World and The Osbournes were all the rage, heralding a new era of mass media consumption. Fuelled by the internet’s increasing accessibility, we were entering a true digital age, evidenced by our subsequent seamless transition into a world of smartphones, social media and streaming platforms.

With executive producer Moustapha Akkad’s insistence that Myers remain alive for future sequels despite his decapitation in 1998’s Halloween H20: 20 Years Later, Brand developed a unique premise inspired by Orson Welles’ 1938 radio broadcast of HG Wells’ ‘War of the Worlds’. Whereas Welles managed to convince his listeners that aliens were invading Earth, Brand sought to reverse that concept by staging a live webcast from inside Myers’ childhood home in Haddonfield, with viewers at home believing that the ensuing carnage was all part of the show. Titled Halloween: MichaelMyers.com during pre-production, Resurrection was meant to signal a rebirth for the franchise, with Myers stabbing his way through standalone storylines.

Resurrection’s unfamiliarity proved to be its undoing. As the first Myers-based Halloween film not to feature Jamie Lee Curtis’ Laurie Strode or Donald Pleasance’s Dr Loomis as central protagonists, fans denounced it as soon as they saw the former meet her demise early on at the hands of The Shape, retconned back from the dead. The ill-advised decision to kill off horror cinema’s quintessential Final Girl capped off an otherwise impressive opening 15 minutes, which takes place inside the sanitarium where Laurie was committed following H20’s conclusion.

Laurie’s faking catatonia inside a creepy asylum and the subsequent chase down its dimly lit corridors were atmospheric homages to 1981’s Halloween II, another sequel directed by Rosenthal. It also showcased a calculating Myers retaining the stealth and cunning barely seen since the first two Halloween films, emerging victorious over his estranged sister before handing his blood-soaked blade to a patient with an encyclopedic knowledge of mass murderers, then disappearing into the shadows like only he can.

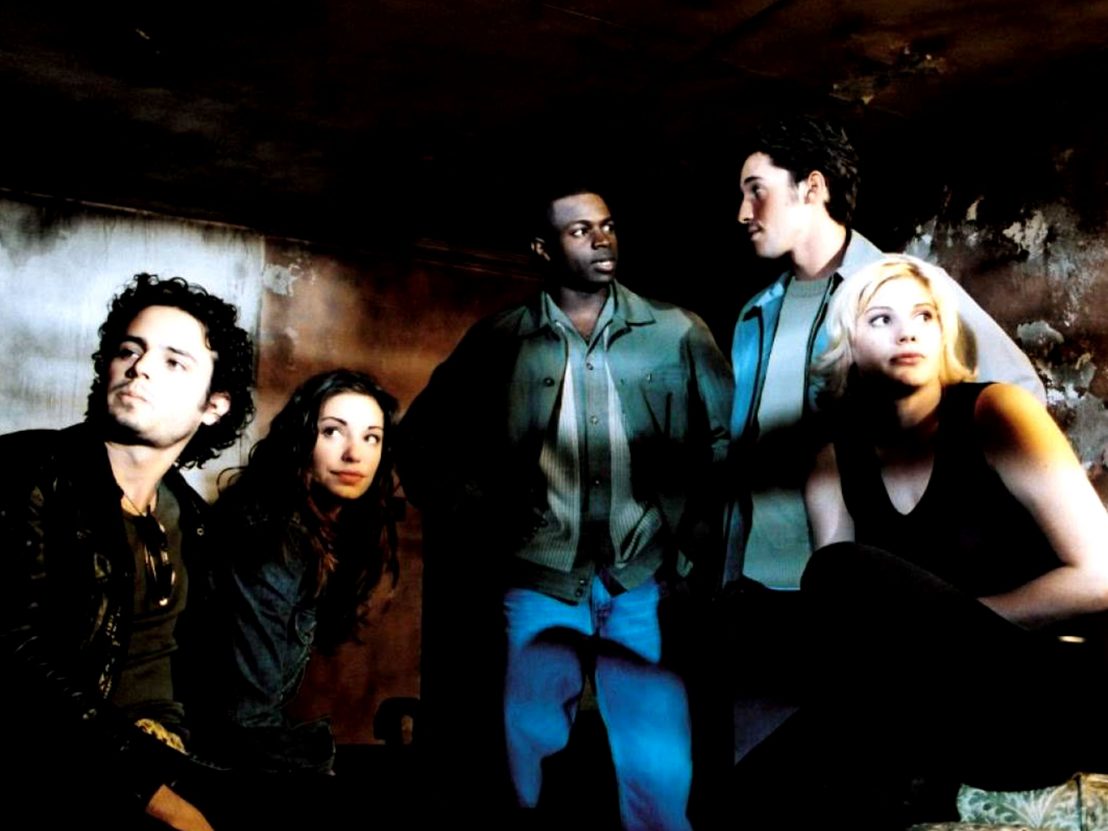

Brand’s novel idea doesn’t come into play until the story shifts back to Haddonfield, where we’re introduced to a bunch of fame-hungry university students selected to take part in a reality web series called ‘Dangertainment’. As instructed by the show’s hosts, played by Tyra Banks and a hilariously hammy Busta Rhymes, the group have to spend Halloween night inside Myers’ childhood home with the purpose of attempting to unravel his murderous motives. The six contestants, each of them sporting headcams and laden with quirks xeroxed from the teen slasher renaissance of the late ’90s, are tedious murder fodder.

Even Sara, the film’s Final Girl, serves as a regrettably dull counterpart to the iconic Laurie, with her only true confidant being an online pen pal named Deckard who tunes into the broadcast at a party later that evening. Once inside the Myers house, they run into fake evidence, rigged props, and Rhymes’ Freddie dressed up as Michael, before realising to their horror that they are actually locked in with The Shape himself. Cue mass slaughter via pixelated web streaming. In the end, Sara and Freddie, who stay one step ahead of their homicidal host thanks to Deckard tracking The Shape’s movements on webcams and texting them his whereabouts, manage to defeat Michael by frying him alive with stray electrical wiring.

Despite Resurrection’s lopsided execution, Brand’s screenplay successfully satirises the public’s obsession with celebrity, serial killers, and the exploitation of tragedy. Also interwoven is the flawed idea that someone like Michael Myers can be decoded, given that the hapless webcasters’ primary goal is to figure out what led Myers to kill when the truth is that he has no motive. Ironically, this brings it more in-line with the 1978 original than most other Halloween films.

If anything, Resurrection’s premise is a clever metaphor for the entire filmic experience. The contestants are the actors, the Dangertainment staff are the crew, Deckard and his fellow partygoers are the audience, and the asylum patient from the beginning represents the hardcore horror aficionado who spews facts and collects masks. Even Freddie, whose kung fu moves immortalised him as the Halloween franchise’s Jar Jar Binks, channels Hollywood’s need for greed, proclaiming at one point that “America just wants a little razzle dazzle, and us being the ones to give it to ’em, I don’t see nothin’ wrong with that”.

With TikTok, Twitch, and true crime podcasts and docuseries now dominating the media landscape, Resurrection’s underlying message may resonate with a modern, tech-savvy audience. It’s certainly apropos for a generation who have found fame in cyberspace. It may not be the best Halloween sequel, but it deserves some kudos for foreshadowing the rise of digital broadcasting at a time when ‘unscripted’ content was in the ascendancy. Irrespective of your own tastes, wouldn’t you tune in to see a group of insufferable influencers locked inside “the birthplace of evil”?

Published 14 Oct 2021

By Thomas Hobbs

The director’s satirical 1994 horror explores what happens when society embraces its worst monsters.

Michael Myers runs amok once more in director David Gordon Green’s strangely lacklustre slasher sequel.

With a pinch of Hammer Horror and a dollop of ’80s gore, this meta horror is the boldest in the series.