Roger Ebert said that Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate was, “the most scandalous cinematic waste,” he had ever seen. Vincent Canby called it, “a forced, four-hour walking tour of one’s own living room.” Pauline Kael was so incensed by this “numbing shambles” that she deemed it to be, “a movie you want to deface; you want to draw moustaches on it, because there’s no observation in it.”

Since its release in 1980, however, critical opinion on the film has shifted dramatically. In a 2015 video essay, Richard Brody went as far as describing Heaven’s Gate as, “one of the most wrongly reviled movies ever made,” claiming that initial reviews showed how, “critics sought to outdo themselves in the art of stone-throwing, each one’s hostile cruelty shielded by everyone else’s.”

Today, the controversy surrounding the film’s production is probably more familiar to the average cinemagoer than the film itself. When we think of Heaven’s Gate, the phrase that comes to mind is “unqualified disaster”, that ludicrously hyperbolic deathblow pronouncement offered by Vincent Canby. We think back to ‘Final Cut’, producer Steven Bach’s slanted chronicle of “The Film That Sank United Artists”, publish in 1999. Some of us might even recall the 108-minute “Butcher’s Cut” of Heaven’s Gate that Steven Soderbergh (under the pseudonym “Mary Ann Bernard”) mangled and released on his website in 2014.

But what is Heaven’s Gate really about? I prefer the French writer Yannick Haenel’s synopsis, which appears in his intoxicating celebration of Cimino’s aesthetic in his novel ‘Hold Fast Your Crown’: “It’s a film about the criminal founding of America…[it] shows how the rich eliminate the poor… it tells of class struggle… through the flickering lens of ceremonies. And there’s sex, dancing, and death.”

That’s not a bad alternate title. At its core, Cimino’s western brilliantly depicts the malignant mentality of the ruling class during America’s so-called Progressive Era. Cimino guides the viewer along a roadmap of dual lifestyles: the privileged elite celebrate their status with extravagant ceremonies, while simultaneously ostracising the immigrants they perceive to be thieves, savages and murderers, before finally, with the support of the US government, carrying out a chaotic and brutal extermination.

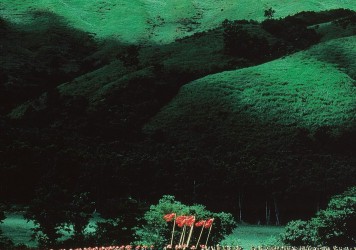

Meanwhile, 1890s Wyoming is made to look like Paradise before the Fall: lush blue skies dusted with cotton-spun clouds; mountain ranges spiking up towards the heavens; shafts of white light pierce through mud- and dust-caked windows. Much has been made of Cimino’s unwavering dedication to period authenticity. “He would actually paint by selecting extras and put them into the right place,” cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond says in the 2004 documentary Final Cut: The Making and Unmaking of Heaven’s Gate. “He painted [with] people.” According to the AFI Catalogue of Feature Films, Cimino was nicknamed “the Ayatollah” by the crew members because he required “every article of clothing, every structure, every sign [to be] based on a photograph of the period.”

The scale of the film’s production is unfathomable by contemporary standards. Faced with daunting prospect of having to build a railroad through a town, Cimino instead decided to construct an entire town around an existing track. (Apparently, what he referred to as a “standard gauge railroad” was extremely rare to come by.) The director gave himself the responsibility of managing one thousand extras, coordinating 90 teams of horses, and utilising a train that had to be shipped across five states – and that was just for one sequence.

In a 1980 interview with American Cinematographer, Cimino claimed to have even directed the elements: “We needed wind to blow across the battlefield. We had made no provisions for wind, but somehow I kind of raised my hand… and the wind came up. And I raised it again, and it came up harder. Needless to say, the crew was astonished that it happened.”

The upshot of this obsessive attention to detail is quite astonishing: every aspect of Heaven’s Gate somehow gives the impression that the camera has traversed time and space in order to capture what it actually looked, felt and sounded like to exist in 1890s Wyoming. It’s the kind of film you can almost smell. This effect reaches a fever pitch during the climactic battle, which acts as an inverted restaging of the grandly realised post-graduation dance sequence that opens the picture. The pageantry of the privileged Harvard men is viciously satirised, in a sense, by a prolonged finale so smothered in dirt and debris that it’s hard to make out the action. It’s pure mayhem, and just when it seems that a truce might be declared, Cimino delivers one final bloodthirsty standoff before a stunningly unexpected denouement.

Heaven’s Gate is not a perfect film, but it is a remarkable cinematic feat. For all its formal majesty, some of the dialogue and other narrative elements don’t quite work. At times you can sense Cimino striving to sort out his conflicted feelings about how to establish plot points in the first act so that they pay off effectively in the third. John Hurt remains an unhinged caricature from beginning to end. But, above all, Heaven’s Gate stands as an eye-opening anomaly of film history.

Arguably no other film before or since has been more breathtaking in scope, and no filmmaker has attempted to realise their vision with such steadfast, some might say stubborn, commitment to authenticity. Cimino simply refused to cut corners. He referred to this process as, “demolishing the wall… the idea is to smash that wall, move around – otherwise it’s a proscenium. You want to get to the real world. After all, movies have something essentially magical about them.”

The result of Cimino’s art and ardor is something truly awe-inspiring, a crazed epic that, for better and for worse, has no equal in American cinema.

Published 16 Nov 2019

By Dan Einav

Sergio Leone’s landmark western, which turns 50 this year, is a fascinating product of its time.

The Japanese director’s bleak and beautiful 1985 film returns to cinemas.

Arthur Penn’s seminal crime thriller owes a lot to the likes of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut.