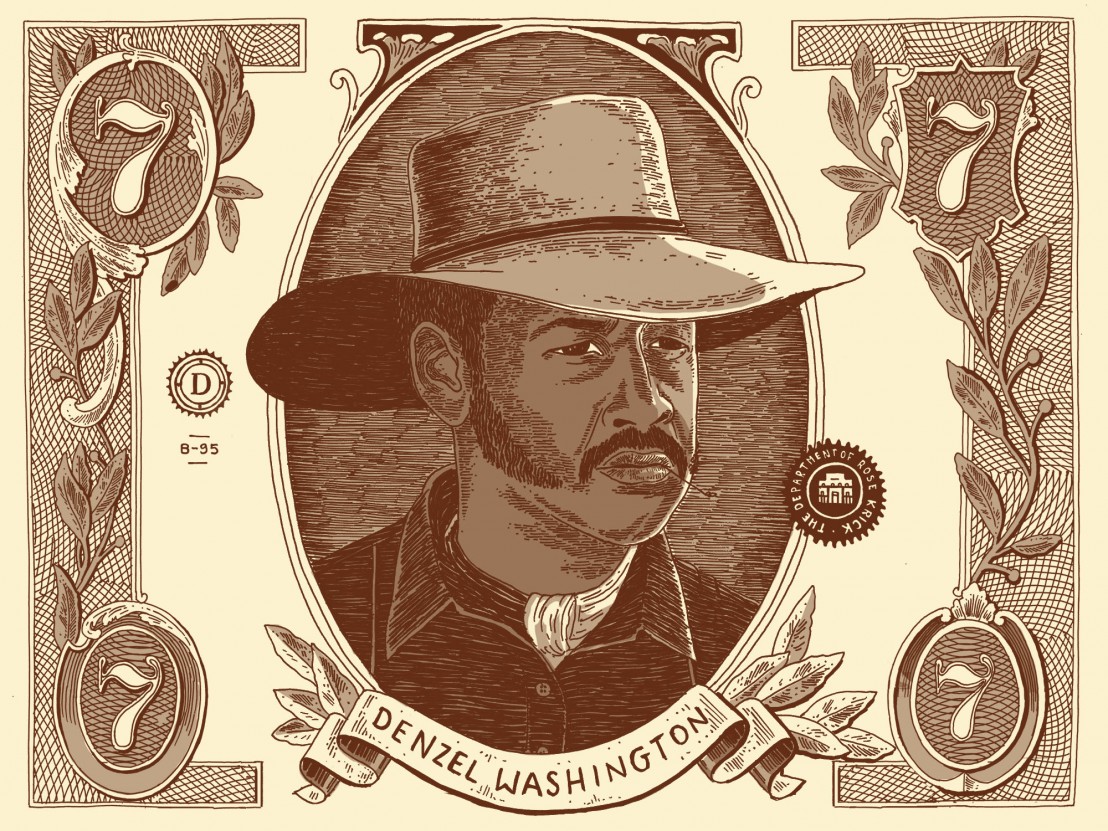

In a landscape of total celebrity saturation, is this enigmatic Hollywood icon is the last of the pure movie stars?

Movie stardom is a fickle thing. You’re built up, you’re torn down, you’re papped, you’re slandered and you’re expected to accept it all. And if, sooner or later, you punch a photographer or jump on a couch or have a high profile fling, that’s all part of the deal too: the only bad publicity is no publicity. And yet: Denzel Washington. In between his movie roles and award podium appearances, where does he go? How has he achieved a 44 feature-strong career (a remake of The Magnificent Seven will be number 45), and maintained a near-unrivalled level of fame for decades, while remaining such an unknown quantity?

There are some films in which he’s incandescent. He is still the only African-American to have won more than one acting Oscar (he has two). He is a Tony-winning theatre actor, the author of a non-fiction bestseller, a soon to be three-time film director, as well as a father of four and a husband of 33 years. None of this is small change, and yet none of it is the stuff of thrilling magazine profiles. Start investigating Washington’s star persona and, pretty quickly, you end up writing a piece that more closely resembles a CV. To find the real Denzel Washington, you need to rush the fortress from several sides at once.

“I got a part in a movie in 1986. I call it The N*gga They Couldn’t Kill – he raped a white woman and they tried to electrocute him but it didn’t work… And I called Sidney [Poitier] and said ‘Man, they offered me $600,000 for The N*gga They Couldn’t Kill!’ And he told me ‘the first two or three or four films you do in this business will dictate how you’re perceived.’ I turned it down and six months later I got Cry Freedom.”

This quote is from a 2010 interview for TimesTalk. Cry Freedom was the breakout for Denzel Hayes Washington Jr, but it was actually his fourth theatrical feature film. His first had come six years prior, after a couple of TV bit-parts and before he landed his regular slot on hospital drama St Elsewhere. 1981’s Carbon Copy sees Washington co-starring with George Segal and directed by Michael Schultz, a black filmmaker and more recently a TV stalwart on shows such as Brothers and Sisters, Arrow and Black-ish. Back then, Schultz specialised in films like 1977’s Car Wash in which Richard Pryor heads a multiracial ensemble charting a chaotic day-in-the-life of an LA car wash facility. It’s a comedy with an edge of social comment, and Carbon Copy also fits this bill.

Washington plays Roger Porter, who reveals himself as son of the wealthy, successful (white) Walter Whitney (Segal). The wacky results become more sober and incisive as the story unfolds. But the film is dated, and the sexist portrayal of Whitney’s rapacious white wife blunts its progressive credentials. It’s hard to tell if Whitney turns his back on his riches to forge a relationship with his black son out of newfound paternal affection or simply to escape the vacuity of his old loveless lifestyle, to which he is now “woke”.

However, Washington is supremely at ease, affable and charismatic. His effortless savoir faire may even work to the film’s detriment: the twist at the end is that Roger is not the ill-educated, no-hoper street kid Whitney first believes him to be, but a second year pre-med student at his father’s own alma mater who took time out from his studies to teach Dad a much needed life lesson about judging by appearances. Problem is, Washington’s sophisticated aura of watchful, ironic intelligence is so palpable that there’s no moment at which we do not understand that Roger is playing a trick on Whitney.

Hence no surprise when the reveal occurs. But what’s even more striking about this debut lead is how, maybe more than any that came after, it neatly correlates to the stardom that Washington was on the verge of achieving. Here the then-progressive agenda is that a black man could be seen as capable of succeeding within a society whose edifices are temples of blinding whiteness. A more modern viewer might desire to critique those institutions more radically than Carbon Copy ever does. But this is the social crucible in which Denzel Washington, the movie star, was forged. For context, consider that Carbon Copy premiered when TV shows like Diff’rent Strokes and Benson were in their heyday (both representations of blackness played for fish-out-of-water laughs by placing it in a white context), years before even The Cosby Show first aired, and a full decade before the wealthy family that Will Smith moved in with in The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air were themselves allowed to be black.

The model established by Poitier in his quote taken from Washington’s unusually candid TimesTalk interview, films like Carbon Copy, A Soldier’s Story and Cry Freedom, for better, for worse, for richer, for blander, have dictated how Washington has been perceived ever since. And those films were products of their times – times which have a-changed. Meanwhile, the conception of Washington as a public figure has remained defiantly stable.

Outside his films, Washington is rarely as unguarded as in the TimesTalk interview quoted above, and only very rarely courts controversy. One instance occurs during that session, when he mentions how he likened slavery to the Holocaust in the company of some Jewish people – even the audience in attendance seems unsure how to react until he reassures them. Another is when he reportedly blew up at Quentin Tarantino on the set of Crimson Tide over Tarantino’s nervous-reflex-like tendency to sprinkle his script rewrites with racial epithets. And he became the unwitting eye of a minor firestorm when one of the leaked Sony emails suggested that the proportionately disappointing overseas box office for his 2014 film The Equalizer proved that the international audience was “racist.”

While the producer in question was at David Brent-ian pains to clarify that he himself was not being racist (“I personally think Denzel Washington is the best actor of his generation.”) he did implicitly urge the Sony powers-that-were to reconsider casting African-American leads in general, and Washington in particular, in that type of film. Simply as a matter of savvy business strategy. Advice, incidentally, clearly not taken: The Magnificent Seven is a Sony production and The Equalizer is on track for a sequel. Beyond those isolated incidents, Washington has maintained an image of charming, good-guy decency that’s so impermeable as to be double Teflon-coated.

It’s hard to find anyone with a bad word to say about him – with the exception of actor Bronson Pinchot whose assessment of his Courage Under Fire co-star at the AV Club (“one of the most unpleasant human beings I’ve ever met in my life”) is as scathing as it is unique. Far more often you hear co-stars and collaborators extolling Washington’s professional and personal excellence – from Spike Lee insisting he’s, “the greatest actor of all time, period” to Tom Hanks first calling out his Philadelphia co-star who “shone because of his integrity” at the Oscars, and more recently introducing him at the Golden Globes as an “artist who defines the times we all live in.”

Washington comes across in interviews as a humble man almost embarrassed by his own magnetism, with an immense talent for which he is grateful to God (he is a devout Pentecostal Christian who reads from the Bible daily). And his distinctly un-Hollywood lifestyle, long marriage and private politics (aside from a spell as an outspoken Obama champion during the 2008 campaign) certainly haven’t contradicted that image. In fact he’s been on-message almost to a fault, as though his fame has a script from which he never strays too far. Some of his favourite aphorisms seem to weave their way in and out of interviews, films and public appearances to the point of white noise.

The quote, “You’ll never see a U-Haul behind a hearse,” for example, a riff on “you can’t take it with you,” appears in his 2006 book ‘A Hand To Guide Me’; in the January 2008 issue of O Magazine during an interview with Oprah; in 2009’s The Taking of Pelham 123 (spoken by Washington’s character); in a January 2010 press junket; twice at a May 2014 talk to acting students; and it forms a central tenet of his 2015 commencement address to the graduates of Dillard University. It’s clear Washington takes his responsibility as a role model too seriously for careless off-the-cuffness, but it also feels like an offshoot of a more classical, codified approach to stardom than our spontaneously confessional age, all snapchats and selfies and embarrassingly emoji-laden tweets, tends to promote. There’s a reason why there aren’t too many Denzel Washington memes, and it can’t be that he’s never looked sad while eating a sandwich.

“There’s a reason why there aren’t many Denzel Washington memes, and it can’t be that he’s never looked sad eating a sandwich.”

Movie journalists and film commentators have tried to define the essence of Washington’s stardom. Film historian Cynthia Baron, who literally wrote the book on Washington (part of the BFI ‘Star Studies’ series), invokes a new kind of “Hollywood stardom [that] no longer requires a link with whiteness.” But Baron also relates Washington’s pioneering achievements to a cinematic tradition of yore, summoning Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Fred Astaire and Cary Grant as comparison points. Similarly, in 2014, Variety’s Brent Lang wrote an article titled ‘Why Denzel Washington May Be the Last Pure Movie Star.’ Its tone is wholly admiring but it doesn’t take a genius to extrapolate a downside to being described as such: that the era in which his star persona naturally fits is passing.

So Washington is both pioneer and throwback, both the first and the last. And that’s something he is aware of. Talking to The Guardian in 2013, he said, “Being African-American, there were no big movie stars to hang out with anyway, not when I was starting out, they were just the third guy from the back! For whatever reason, I never befriended any white actors.” It sounds like a lonely position to be in, a star forging his own path just slightly ahead of the wave that would follow soon after. Timing is everything, and Washington was picking up his first Oscar (an obvious marker for mainstream acceptance) for the Ed Zwick-directed, white-mediated 1989 film Glory, just a few months after future collaborator Spike Lee released black cinema touchpoint Do The Right Thing, and around a year before John Singleton’s Boyz N The Hood hit screens. With no stardom template to follow, it’s hardly surprising that Washington controlled his public image so carefully. Which also means that interviewers often seem unprepared for the frank, forceful Washington that occasionally shows up. Roger Ebert interviewed him around the time of his outstanding turn in Malcolm X and wrote warmly that, “What was surprising for me, talking to him, was how political he was – how willing to continue the discussion that Malcolm X begins in the film.” Yet in that same interview Washington claims, “I don’t speak for my work; I like to let my work speak for me.”

More recently, in that 2013 Guardian piece, Xan Brooks makes a point of stressing the disconnect between the Flight-era Washington he meets – “talking up a blizzard, he’s talking to keep warm; spouting off in great, rousing, charming gusts,” and the Washington he probably expected, a megastar by any standard, yet one who you “could probably walk past […] in the street without so much as a backward glance.” Again, even there, the interview ends with Washington, having effortlessly charmed and disarmed with the full force of his personal magnetism, calling out as an afterthought: “What’s a celebrity anyway? Paris Hilton’s a celebrity. I’m just a working actor.”

Read more in LWLies 66: The Magnificent Seven issue

Get the MagSo what does the work say about Denzel Washington? On the one hand his filmography promotes the idea of him as a star of rare integrity: can you think of any other A-lister without a single sequel or franchise to his name? (Even if that changes with The Equalizer 2, it was an unprecedented 35-year streak). Even Tom Hanks, whose own fame and likeable everyman persona probably most closely correlate to a “white version” of Washington’s, has gone back to the Da Vinci Code well a couple of times now and has voiced three Toy Story movies. Washington hasn’t ever gone the family film route, has never voiced a feature animation and, in the years since Carbon Copy, has appeared in exactly two comedies: The Preacher’s Wife from 1996 and 1990’s forgotten, racially- motivated organ transplant farce, Heart Condition.

What makes Washington’s stardom so unusual is that, for better or worse, it is predicated on the kind of grown-up dramas people like to complain that Hollywood doesn’t make anymore. And unlike, say, erstwhile co-star Samuel L Jackson, Washington does not take supporting roles in big-budget blockbusters: he’d rather lead a smaller film. This sets limits. Washington has never been a huge money- spinner in the manner of Tom Cruise – only five of his films have made more than $100m in the US, and his best performer – Ridley Scott’s American Gangster – tapped out at $130m domestically.

It has also proven something of a creative limitation. Outside of the four films Washington has made with Spike Lee, and a handful of others that distinguish themselves for other reasons, there are an awful lot of rather samey filler titles: Ricochet, 2 Guns, Virtuosity, John Q, Out of Time, The Book of Eli, The Pelican Brief, The Taking of Pelham 123, Deja Vu, The Bone Collector… Some of those films are pretty good for what they are, but memorable star vehicles they are not. The inexplicably popular Man on Fire is probably the paradigm there, but those traits carry all the way up to 2014’s The Equalizer and, probably, beyond.

The heavy-lifting, capital-P performances can mostly be found in the other strand of Washington’s career to date: the portraits of real-life historical figures. From anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko in Cry Freedom to Ruben ‘Hurricane’ Carter in The Hurricane and fictionalised Pvt Trip in Glory to antihero Frank Lucas in American Gangster, these are the turns that established his practically trademarked reputation as one of the best actors of his generation. But they also suggest he’s one of the most classical, to the point of old-fashioned, as they all belong to the “inspirational true-life story” category that has, for so long, been the Hollywood establishment’s idea of acceptable prestige. Add to that heady mix the slightly anomalous Oscar win for the more generic Training Day, and you have a good idea of the bullseye area of his mainstream appeal.

Like many masterpieces, Spike Lee’s Malcolm X was not immediately recognised as such. And maybe it’s to be expected that the (predominantly white, if it needs to be said again) establishment would have a hard time wholly embracing a biopic of the most divisive of black icons, coming from the outspoken director of the powder keg street opera, Do the Right Thing. But while the epic yet humane scope of Lee’s achievement might have taken some time to sink in, Washington’s Oscar-nominated performance was lauded straight away. And he is unmistakably brilliant, from his wolfish grin and Rufus T Firefly walk during the riotous, zoot-suited quasi-musical opening, to the convincing portrayal of X’s religious conversion and subsequent radicalisation as part of the Nation of Islam, to the eventual, quieter revelations after his trip to Mecca.

It was also a kind of unspoken rebuke to the other, better-known side of his star persona. As Ashley Clark, writing for The Guardian, put it: “Lee’s film was a powerful statement against an entertainment culture which routinely prioritised the experience of white saviours in civil rights narratives (see: Cry Freedom, Mississippi Burning), or sweetened the bitter pill with soothing depictions of interracial friendships (The Long Walk Home).”

And yet, even while they may not have been the film’s primary audience, Washington’s performance humanises Malcolm X for white American viewers too. In his skilled, multifaceted turn, Malcolm is neither the infallible idol his supporters saw nor the crazy-mirror boogeyman version of Martin Luther King Jr that mainstream culture was coached to view him as. Washington renders Malcolm X as a man, and if it isn’t his absolute greatest performance, it very well might be his most lastingly important.

“In a just world, the sadly underrated Devil in a Blue Dress would have kicked off Washington’s first franchise.”

Lee didn’t only get one great performance out of Washington, he got four. Their collaborations – Malcolm X, Mo’ Better Blues, He Got Game and Inside Man – amount to a separate sub-category of excellence within Washington’s extensive catalogue. Maybe it’s because other regular collaborators like Tony Scott and Antoine Fuqua, employ Washington as a star, whereas Lee employs him as an actor. The characters portrayed in each of Lee’s films do not fit the mould of the man’s-gotta-do archetype Washington plays over and over again elsewhere.

This is perhaps best exemplified by his perfectly nuanced turn as the convict father trying, and largely failing, to connect with his son for reasons both noble and ignoble in the tremendous He Got Game (this one might well be his actual greatest performance). Lee is one of the few directors to give him roles that do not rely on his charisma – in fact they require him to tamp it down in service of a deeper truth about real, convincingly broken men. It’s that approach that makes Malcolm X feel less like a hagiography than a sympathetic eye-level account of history as lived by people, not icons.

And it lends even their most commercial film, Inside Man, the texture and sly wit of a character piece, disguised as a fun cat-and-mouse heist thriller. Washington seems to trust Lee with narratives in which his character loses in a way he perhaps doesn’t with any other director. Tellingly, his two biggest regrets, as he told GQ in 2012, are turning down two films that presented a similarly more complex idea of ‘winning’ and ‘losing’ than the more generic fare he often accepts: the Brad Pitt role in David Fincher’s horror-thriller Se7en and the George Clooney role in corporate psychodrama Michael Clayton. Of the latter he admitted frankly, “It was the best material I had read in a long time, but I was nervous about a first-time director, and I was wrong. It happens.”

And the four Lee films are not the only notable outliers in Washington’s filmography. There was his genuinely difficult role as the homophobic lawyer in Jonathan Demme’s Philadelphia which Tom Hanks rightly said, “really put his film image at risk.” His two films with director Carl Franklin, Out of Time and Devil in a Blue Dress, also showcased a different conception of Washington’s appeal: a sleazier, sexier side, involving probably the most graphic sex scenes the usually clean-cut star ever engaged in. In a just world, the sadly underrated Devil in a Blue Dress would have kicked off Washington’s first franchise: the Easy Rawlins books by Walter Mosley were ready and waiting and never had Washington (and indeed Don Cheadle as Mouse) more perfectly slid into a character.

In a very brilliant Literary Hub piece on Harper Lee’s changing legacy, Kate Jenkins says that, “sometime between the publication of ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ and, let’s say, the invention of Twitter, white Americans got the strange idea that ours was a “post-racial” society.” Washington became a star during this era and his stardom, which has been remarkable for its consistency and unchangeability over decades of ceaseless work, feels like part of that post-racial dream. But we now live in ‘Go Set a Watchman’ times, when the comforting paternalism of Atticus Finch is revealed to have been a kind of condescending racism all along and when the very term “post-racial” is most usually accompanied by the word “myth”.

Washington did an amazing, unequalled job of becoming a Hollywood star (which, let’s not forget, is a mainstream – read white – construct) when the odds were wildly stacked against him. Rather like the “Ginger Rogers paradox” for women (Rogers did everything her better-paid co-star Fred Astaire did, only backwards and in heels), in order to achieve an equivalent level of fame and influence, Washington had not only to be better at his job than most of his white counterparts, he had to be personally unimpeachable on every level: God-fearing, morally incorruptible, unquestionably respectable, a paragon of virtue. And that’s from a mainstream perspective.

From the point of view of his standing within his own community, the stakes were even higher. As Chris Rock put it, “being famous as a black guy is a little different than being famous as a white guy. Tom Hanks is an amazing actor, but Denzel Washington is a god to his people. He has a responsibility to his people that Tom Cruise, Liam Neeson, all these guys don’t have. They just make their art.”

Washington successfully negotiated all that for decades, with a grace that, to a casual observer, could easily seem so effortless as to be practically transparent. But now that he has set his mark on Hollywood history as surely as his handprints have been immortalised in cement outside the Chinese Theatre in LA (extreme left of the entrance, between Danny Glover, Walter Matthau, Michael Keaton, Susan Sarandon and Oskar Werner, if you’re curious) he has license, if he wants it, to change, to experiment, maybe even to subvert his image – to give audiences black and white more opportunities to say (as he told The Telegraph in 2013), “we haven’t seen Denzel like that.”

He can take immense pride and is owed a massive debt of gratitude for taking on the mantle of “the last pure movie star” with such intelligence and integrity. But it would be exciting now to see him evolve into the first of something else – to see Denzel Washington, at 61, re-redefine what it means to be Hollywood’s brightest black star.

Published 22 Sep 2016

Saddle up with our epic Stetson-tip to Antoine Fuqua’s gritty western remake.

From Body and Soul to Creed, the sports movie has a rich tradition of raising awareness around issues of class and race.

The Magnificent Seven director offers a unique first-hand take on the acting heavyweight’s enduring appeal.