In the opening scene of Shane Meadows’ 2004 film Dead Man’s Shoes, we see two men walking through a desolate rural landscape, across open fields under a leaden sky, towards an old deserted farm on the hillside.

Interspersed are scenes from old family videos. There are snapshots of Christmases and birthdays and fun days out. Joyful family memories captured on fading film. Two brothers still united, but with a darkness descending.

When it was first released, Dead Man’s Shoes was billed as a violent psychological thriller with the feel of a low-budget British western; a man returning to his hometown to exact revenge against those who have wronged him. Meadows wears his influences on his sleeve, paying homage to classic ’70s thrillers like Straw Dogs, while the DIY deliverance of a scorned serviceman also recalls First Blood. There is no doubt that retribution looms large, but this is also a film about loss, the extreme grief felt when a loved one is suddenly taken.

Paddy Considine plays Richard, an ex-Para who comes home to Matlock in rural Derbyshire after several years away. He’s seeking retribution against a gang of local criminals for a tragic incident involving his vulnerable younger brother Anthony (Tony Kebbell), who has learning difficulties.

Richard is angry, wired and determined. He walks familiar streets, but the quiet normalcy of this small northern town is at odds with his mood. He talks of evil, sin and retribution. It’s his duty to make the gang pay for what they did to his brother. Flashbacks in grainy black-and-white are interwoven throughout the film; unhappy reminders of Anthony being cruelly humiliated.

The gang is led by Sonny, played by ex-boxer Gary Stretch. He’s a small-time crook in a dirty vest, followed by a roguish crew of no-hopers. Their mediocre lives are played out in squalid flats surrounded by empty Pot Noodles and porn. They sit around doing nothing, like bored kids, days full of fags and booze and card games. Deals are done with cash exchanged in tatty brown envelopes. They talk big but drive around town in a beaten up old Citroën 2CV.

Richard appears and disappears like a ghost in a gas mask. He humiliates the gang with juvenile tricks which leave them looking like clowns. But his actions become increasingly more violent as one by one the men are taken out. Vengeance is served cold on plain suburban streets. “It’s hard losing someone close to you, isn’t it?” Richard says calmly to one of the men as he shows him the body of his best friend.

The texture of the film changes when we see the brothers together. It feels like Richard and Anthony are just on a camping adventure out in the wilderness. Conversations are handled with care by Richard. He shelters his brother from seeing the violence he inflicts on his behalf, instead he’s, “Just sorting a bit of business in town.”

In one particularly poignant scene, they sit back to back in a couple of abandoned tractor tyres, talking about childhood. Anthony has always idolised his brother. The innocence of their relationship, and the look of love on Richard’s face as he recalls happier times, in sharp contrast with his actions.

We learn, of course, that Anthony is with Richard only in memory – his grief so strong that he takes Anthony everywhere with him; the weight of his remorse as heavy as the army kit bag he carries on his back.

The grief pours out of him in the film’s final stages, during the confrontation with Mark, the last gang member standing. Mark is a father now, a family man, and Richard can’t bring himself to execute him. Instead we witness Richard’s anguish as he tries to make sense of what he’s done, and the guilt he feels for not being there for his brother.

A heart-breaking question reveals Richard’s inner torment: “Was he calling for me, when you tortured him? Was he screaming my name?” “He still is,” comes the reply, confirming the haunting ever-presence of Anthony.

There is tragic redemption in not carrying out the final sacrifice. Instead, Richard begs Mark to let him lie with his brother; he just wants it all to stop. The final dramatic release of his grief is a blessing.

Dead Man’s Shoes is a morality play. When faced with tragedy and grief, a man resorts to the law of the land, as in medieval times. His reactions become primal. This is a film about a brother’s loss and the raw emotions driving him. It shows how in grief, the dark recesses of a man’s mind can extract the justification for his actions. Rage and thirst for revenge replacing acquiescence because he can’t figure out how to feel.

Published 20 Aug 2019

Before Mike Hodges and Michael Caine, there was Masoud Kimiai and Behrouz Vossoughi.

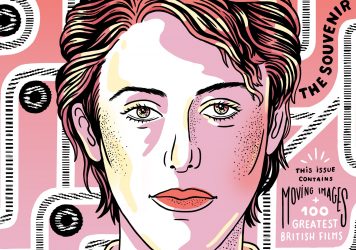

This special, expanded edition of the magazine celebrates British cinema and contains moving illustrations.

By Tom Beasley

Coastal towns have long been a source of nostalgia on screen, but this setting has come to signify something else in recent years.