The constant inventiveness of Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror has taken it from small-scale Channel 4 anthology series to the international platform of Netflix. So when the show’s latest standalone episode, Bandersnatch, was released as the first mainstream piece of interactive storytelling, it wasn’t exactly a shock to the system.

As we’ve come to expect from Black Mirror, its bittersweet perspective is bracingly relevant to the times we are living in – where any sense of control is hard won. Yet what is particularly interesting about Bandersnatch isn’t the interactive element itself but rather how it allows the audience to experience the central character’s mental illness.

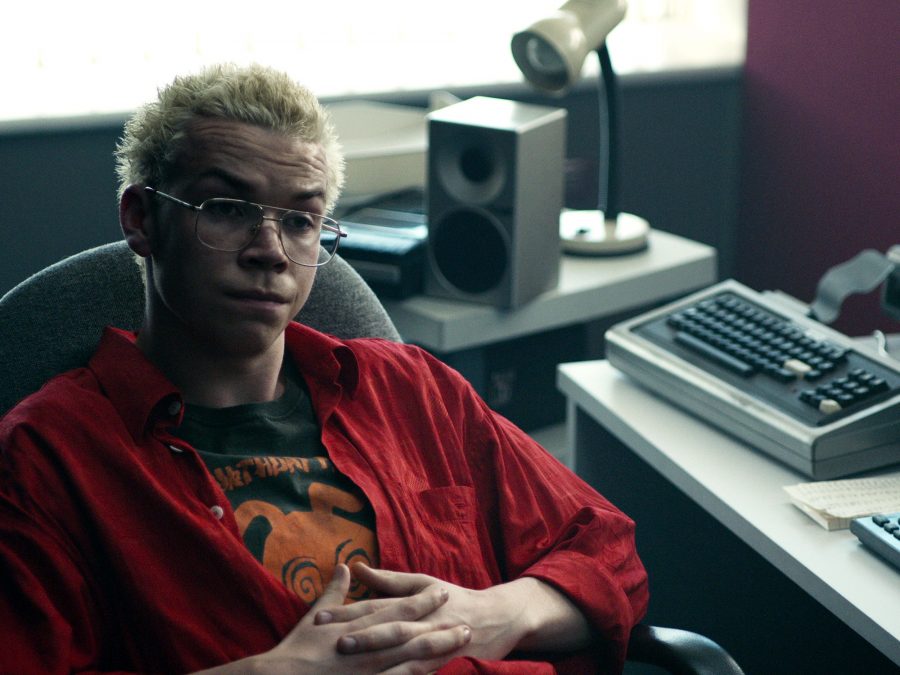

One common symptom of psychosis can be losing control of one’s body, experiencing black outs where you’re unable to recall your behaviour after the fact. By putting us “in control” of Stefan’s (Fionn Whitehead) actions, we are effectively assuming the role of his psychosis. This is something Stefan comes to realise over the course of the episode – in some storylines he directly addresses the audience, accusing us of compounding his mania. But can forcing viewers into this position alter the way we look at mental illness?

Bandersnatch could be accused of reinforcing certain negative stereotypes, as so often in film and television a character suffering from some form of psychosis seems to be always on the verge of committing murder. In this respect, Black Mirror is no different: Stefan is depicted seen as dangerous at best; murderous at worst.

Yet the participatory nature of Bandersnatch has the potential to expand viewers’ understanding of how mental illness works, and how it can affect a person. In short, it makes you think. And not in a throwaway, empathy-driven-tragedy manner, but – through the show’s choose-your-own-adventure structure – actual engagement with the realities of living with mental illness. Being asked to consider the consequences of Stefan’s actions will bring many viewers closer to mental illness than ever before. This level of association alone may provoke a change in the audience’s point of view.

The act of taking away Stefan’s autonomy, too, shows how mental illness often drives people to act in ways they would not choose to while well. We are not given any specifics regarding Stefan’s condition, only that he loses control of his body, takes medication daily and sees a psychotherapist. Yet loss of autonomous thought is experienced by people with a wide range of diagnoses, and so by being vague the show actually becomes more relatable to a general audience.

The structure of Bandersnatch forces the viewer to hastily think up connections between different events, in order to make choices which further the story. One of the key features of psychosis is seeing connections between events where, in reality, there are none. This paranoia is exaggerated in certain storylines, leading Stefan and us to a possible conspiracy. We experience this process alongside our increasingly unstable protagonist.

As someone who lives with mental illness, Bandersnatch resonated on a number of levels, and I found myself obsessively exhausting every storyline in an attempt to become absorbed in its intricacies for as long as possible. I will be watching it again and again. I hope the things which I found so relatable will help those who have never experienced psychosis to understand what it is like in an entirely new way.

Published 30 Dec 2018

By Ella Donald

The new season of the dark social satire features a refreshingly tragedy-free queer relationship.

The gap between movies and video games is closing. But what will happen when the viewer has control over the script?

Before Charlie Brooker’s dark social satire, there was Donald Cammell’s technophobic sci-fi.