At first glance, Bring It On appears to be about little more than the superficial concerns of newly-crowned Cheer Captain of the Rancho Carne Toros, Torrance Shipman (Kirsten Dunst). And that summation is largely true until 20 minutes into the film, when the East Compton Clovers, a cheer team comprised of Black and POC members, are revealed to be the originators of all the Toros’ championship-winning routines.

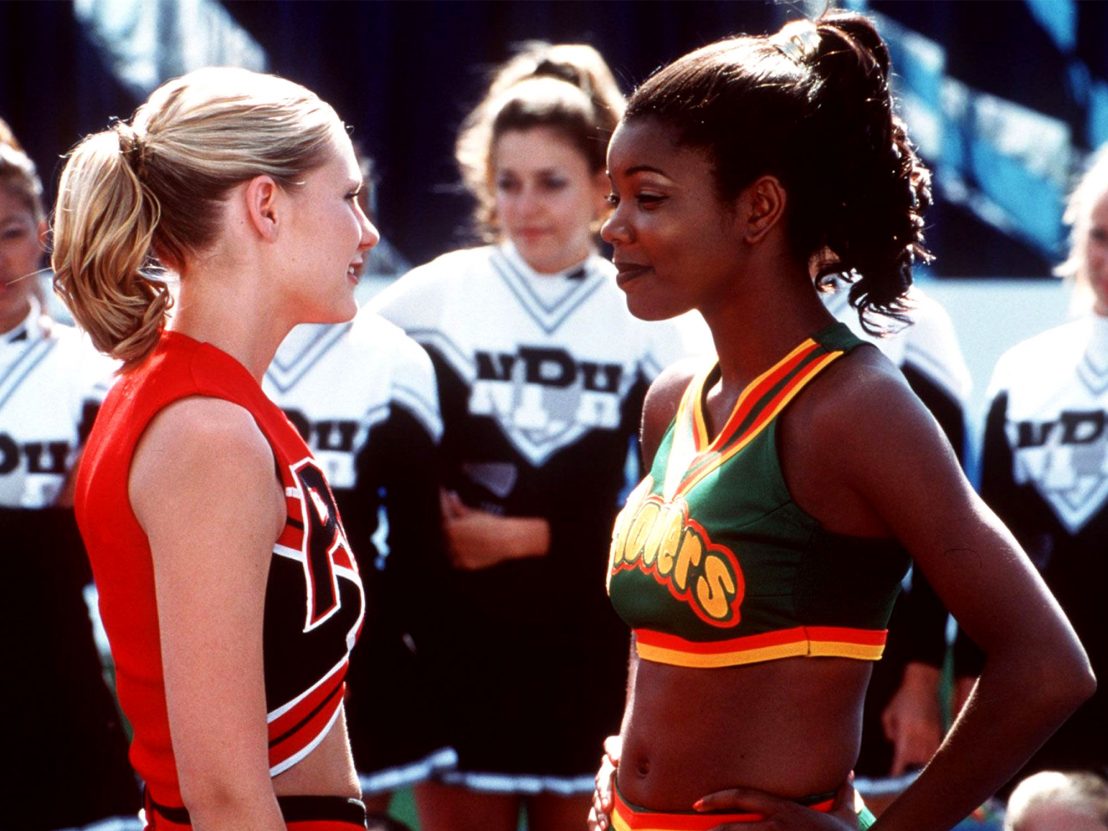

It is at this point the film takes a surprising turn into exploring cultural appropriation and the harm of white privilege, as the Clovers’ Cheer Captain, Isis (Gabrielle Union) confronts Torrance and delivers the immortal line, “I know you didn’t think a white girl made that shit up”.

After a catchy opening cheer dream sequence, Torrance wakes up screaming as the fantasy turns into a nightmare, a manifestation of her fear of failure. Little does she know her worries are completely founded. The blonde, bubbly all-American girl bests everyone in the wealthy, (almost) all-white cheer squad to claim her Captain crown; it’s a classic underdog tale, just not in the way the film initially portrays. “You’re in for a rude awakening,” Missy (Eliza Dushku), the new bad girl cheerleader, tells Torrance.

But this reckoning doesn’t arrive as expected. After telling the rest of the squad of her findings, the initial shock turns to full defence as Torrance is overruled by the team. One squad member interrupts: “I don’t give a shit, we learned that routine fair and square, we logged the man hours… this isn’t about cheating, this is about winning!”Another cheerleader quips: “How are East Compton going to prove anything?” It’s here we see the true face of white privilege, as the Toros know full well they will be able to manipulate a system that has allowed them to thrive. There’s little sense of remorse, only the fear of losing their dubiously gained status.

While Torrance is torn and Missy looks at the rest of the team contemptuously, they too go along with using the stolen routines, their indignation not enough to right the wrongs against the Clovers. Bring It On feels particularly pertinent to today’s climate, where debate around “cancel culture” is rife; the rich white team aren’t really held accountable for their actions. The Clovers confront the Toros on their home turf, performing yet another one of their stolen routines simultaneously with the white squad.

It’s only when the threat of public humiliation rears its head that the Toros decide to find a new routine for Regionals. Ironically, they hire an expensive choreographer who imbues them with the power of spirit fingers, a ton of body dysmorphia issues, and a terrible routine that he has also taught five other squads. Even with the means to secure an expensive coach, the team is still caught cheating and is given a free pass to Nationals on the grounds that they won the previous year. They avoid being “cancelled” despite taking every wrong turn.

“To have an ending where the Black characters aren’t the protagonists but still come out on top feels almost fantastical; in real life, justice often isn’t served.”

While the film’s primary focus is the Toros, we’re also given glimpses into the Clovers’s world and the story is richer for it. Despite their obvious talent, the Clovers are unable to fulfil their potential due to their low-income backgrounds and institutional racism. They work hard and remain unrewarded, so it makes sense that they are a little jaded. At times in the film, the world-weariness that comes from growing up Black in a racist world comes across as hardness. They’re depicted as intimidating, with their white peers almost cowering when they approach (the term “unfriendly black hotties” coined in Mean Girls comes to mind).

Crucially, however, Bring It On just about manages to avoid the “angry black woman” stereotype presented in other dance-based teen movies like Save the Last Dance. Isis is portrayed as a strong leader who cares about gaining her team visibility and the opportunities they deserve. Though unearned, she even gives Torrance advice on how her team could improve and classily side-steps her attempt to give money to the Clovers so they can go to Nationals.

“Why do you have to be so mean,” Torrance complains as Isis rips up the cheque, “I’m just trying to do the right thing” – the irony being that she only attempts to do the right thing when her hand is forced. Isis refuses to play into white guilt and respectability politics and asserts that the Clovers don’t need their help. She’s right – the team is able to secure funding from a local talk show host from their neighbourhood. Discarding a white saviour narrative allows us to see Black and minority enthic communities supporting each other where institutional systems have failed them.

After the high-octane, hairspray-fuelled Nationals, the Clovers beat the Toros to take first place along with a cash prize of $20,000. While in many ways the Clovers are antagonists in the film, their win feels not only deserved but just. This is helped by the Toros feeling content with their second place status; everyone is happy with the outcome. Torrance proves herself as Captain, gets a cute punk boyfriend and concedes to the loss honourable: “You guys were better,” “We were, huh?” Isis agrees.

To have an ending where the Black characters aren’t the protagonists but still come out on top feels almost fantastical; in real life, justice often isn’t served, especially in regards to black girls and women. But in this campy high school flick, Black girls are able to see themselves reach their potential, take control of their agency and succeed on their own terms.

Published 22 Aug 2020

By Beth Webb

Doug Liman’s film exists as a perfect time capsule of youth at the end of a decade.

Nola Darling is reborn in this vital update of Spike Lee’s 1986 film.

By Beth Webb

How the “most smartest” comedy overcame a box office bashing to find a devoted fanbase.