Eggs with hot sauce, dancing in your pants, gossiping over wine with your besties. Despite being released in 1978, Paul Mazursky’s An Unmarried Woman contains many images that will resonate with Millennial viewers. Yet even more relevant is the way the film’s characters own up to and name their feelings. Anxiety, anger, loneliness, sadness, disorientation, happiness. All of these emotions are not only felt by different characters throughout the film but discussed at intimate length.

Radical for its time, An Unmarried Woman centres on a female protagonist who is allowed to be all of these things at once. The woman in question, Erica Benton (played by Jill Clayburgh), is a hotbed of contradictory emotions. This is frequently observed by the various men in her life, who complain that she gives them a headache or is “curious” and “complicated.”

Even when she becomes single, Erica is never singular. Her expressions are always multifaceted. After an emotionally turbulent day in which she discovers that her husband, Martin (Michael Murphy), has decided to move in with a 26-year-old he met buying a shirt in Bloomingdales, Erica catches sight of her puffy-eyed face in the mirror. She contemplates it and groans, pulling her chin down with dissatisfaction. Then she snort-laughs and exhales, revealing a steeliness to her character with the line, “Balls said the Queen! If I had ’em I’d be King!”

Mazursky’s direction emphasises the ebb and flow of emotional recovery. Erica is often shown in motion – jogging, dancing, ice-skating, or simply undressing – and there are several instances where the camera tracks and then circles around her. After learning of her husband’s betrayal, the camera pulls back as Erica walks down the street, her face frozen in open-mouthed shock.

It then pivots, follows and eventually overtakes her in a 360 manoeuvre that conveys the vomit-inducing disorientation she is experiencing. Later, when the darkness appears to be lifting with the possibility of new pastures and romance, Erica goes ice-skating. As she glides along the ice, so the camera rotates to giddying effect.

Couple’s therapist and podcast host Esther Perel recently gave an interview in which she declared that love was “not a permanent state of enthusiasm… it’s a verb… an active engagement with all kinds of feelings.” An Unmarried Woman recognises that. Erica’s marriage is depicted as an interplay of conversation, frustration and passion, in which she and Martin seemed at once bored by and adoring of each other, often within the space of a few minutes. The film is imbued with Perel’s sense of impermanence and fluidity. As Erica says, she is “trying” to be an independent woman. It is a verb and thus an ongoing process.

This notion of fluidity is true not just of Erica. One of her best friends, Elaine (Kelly Bishop), is straight-talking and sardonic. “Does she fuck him or does she adopt him?,” she asks of another friend having an affair with a 19-year-old. Later, she muses on the benefits of having a “pure sex” relationship: “I like my job, my friends, my holidays.” And yet she is also granted a moment of quiet despair in which she admits to having shattered self-esteem and is reliant on the support of her friends to pick her back up. The contradictory nature of human emotions is constantly on display. “You can be a bastard and have talent,” says Erica’s new lover of a fellow artist with wanton ways and a penchant for stepping over the line.

The title of Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story similarly alludes to a sense of ongoingness. It situates the drama in the present tense and signals an unfolding of events. Whereas ‘divorce’ or even ‘break up’ can imply a bruising finality, or even something explosive, ‘marriage story’ sounds like something that might continue long after the matrimony has been legally dissolved. An Unmarried Woman exists in the same mercurial realm. Erica was a married woman, and now she is undoing and unlearning that sense of self. As her therapist wisely notes, “Your life has been disrupted and discombobulated… [this is] a new life.”

Watching the film in light of my own unwanted break-up, and the subsequent few months where it felt like living inside a washing machine, I felt a deeper connection to Erica. I haven’t been trying to extricate myself from a 16-year marriage, but that idea of discombobulation, of laughter co-mingling with sadness and rage co-existing with retained affection for that person is incredibly on point.

The process behind letting something valued and unique behind is an uphill slog. There will be days where your loneliness doesn’t feel quite so bitter, or the thought of going home with a relative stranger not quite so repellent. There will be days when you dance in your pants and laugh so uncontrollably that a different genre of tears glaze your cheeks. I’ve found there are days that encompass the spectrum of emotion so violently it’s enough to give you whiplash. An Unmarried Woman is cinematic therapy, never more so than when Erica’s actual therapist tells her, “It’s okay to feel lonely… It’s okay to feel anything… It’s okay to feel.”

Published 10 Nov 2019

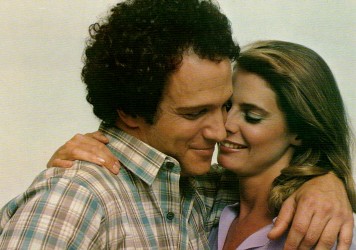

Robert Redford and Jane Fonda play young newlyweds to uplifting effect in this lighthearted comedy.

The actor/director’s 1981 rom-com is one of the best films ever made about jealousy and self-loathing.

By Adam Scovell

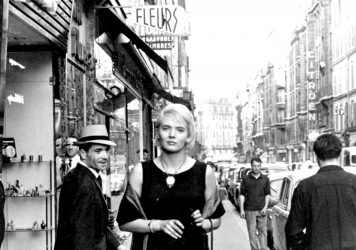

A curiosity in the everyday powers Agnès Varda’s masterful second feature.