Words

Anna Bogutskaya, Charles Bramesco, Kambole Campbell, David Jenkins, Sophie Monks Kaufman, Matt Thrift, Hannah Woodhead, Adam Woodward

Illustrations

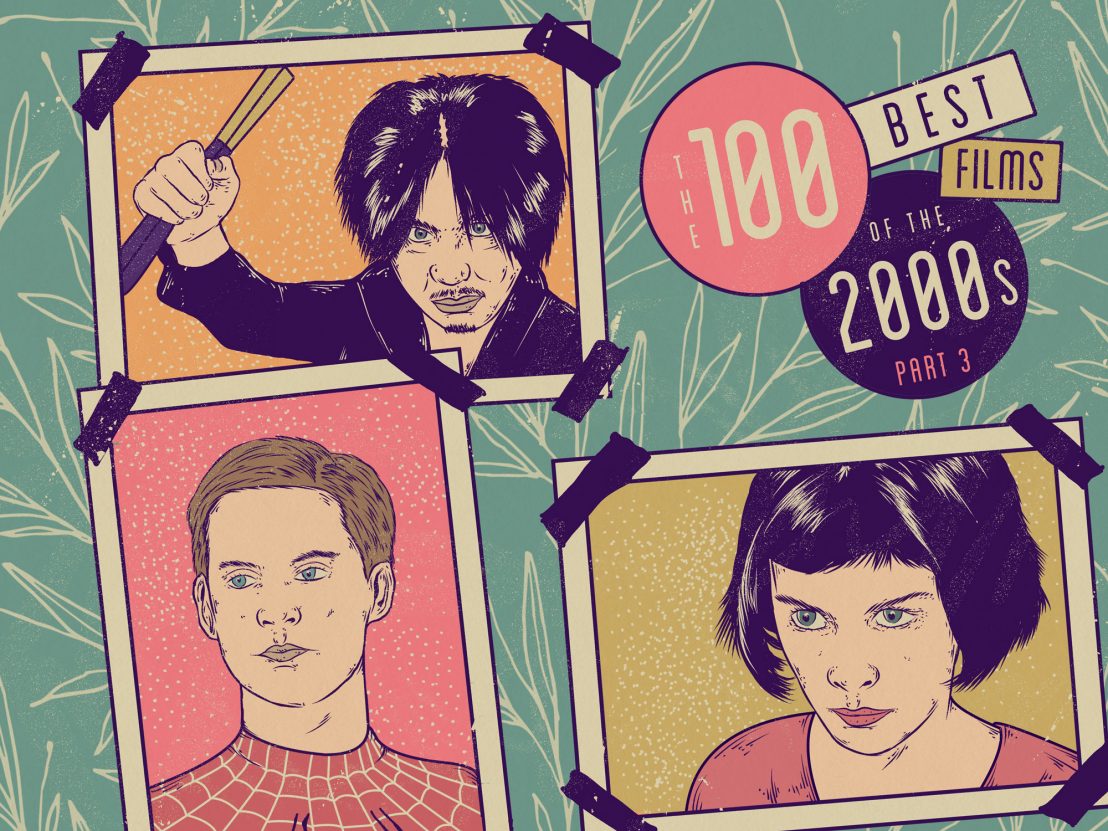

Our noughties ranking reaches the midway point, as Amélie, Oldboy and Spider-Man 2 all make the cut.

After you’ve read this part, check out numbers 100-76, 75-51 and 25-1.

Purists will tell you that Martin Scorsese’s loose remake of Andrew Lau and Alan Mak’s Infernal Affairs can’t hold a candle to the original, but The Departed is a great film in its own right. Taking inspiration from the life of Boston crimelord Whitey Bulger, Jack Nicholson chews up the scenery as the psychopath gangster Frank Costello, while Leonardo DiCaprio and Matt Damon play the cop-posing-as-a-criminal and criminal-posing-as-a-cop who race to rat each other out. Exhilarating and engrossing with that familiar Marty humour, it’s a taut thriller that, by Scorsese’s own admission, “is the first movie I’ve done with a plot.” Hannah Woodhead

Anyone who watched Amélie on release (including this writer) immediately wanted to move to Paris. Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s hyper-saturated look at love, loneliness and connection in a big, unfriendly city is as cheesy as it gets, but still manages to strike a chord. The titular character is a young Parisian woman (Audrey Tautou, single-handedly bringing back short bobs) crafting a romantic scavenger hunt for a man (Matthieu Kassovitz) who is just as adorably quirky as she is. Anna Bogutskaya

I watched Marina de Van’s 2002 film In My Skin for an issue of LWLies celebrating female filmmakers through the ages, and wanted to make sure we covered the less well-trodden grounds of genre cinema, as it’s often neglected in these projects. I was astounded, shocked and repulsed by the film I saw, but was also in awe of what was a superbly conceived and executed body horror of rare erotic intimacy in which a woman (played by writer-director de Van) injurers her leg during a party and instigates a strange relationship with the weeping wound. At once heartbreaking and stomach-churning. David Jenkins

Temptation and virtue go to war in a small Mennonite community, an inner conflict that Carlos Reygadas portrays as an elemental clash on planetary terms. The movement of the sun and changing of the seasons elapse in counterpoint against a Christian’s infidelity and contrition, forming a parable worthy of comparison to Dreyer. With a cast of nonprofessionals and the boundless splendour of nature at his disposal, Reygadas created a towering work that stretches all the way up to heaven. Charles Bramesco

Michael Haneke’s vision of a feverish, sadomasochistic desire is like a trick mirror. Every time you watch The Piano Teacher, a different, disturbingly human angle becomes visible. Adapted from the novel by Nobel Prize-winning Elfriede Jelinek, a tightly-wound middle-aged piano teacher begins a tentative affair with a young pianist (Benoît Magimel). Beneath Erika’s steely exterior and hyper controlled lifestyle is a vast array of fetishes, desires, and furious jealousies that make her (and Huppert’s performance) a fascinating watch. AB

Long before the MCU and DCEU were a thing, Sam Raimi was raking in the big bucks for Sony with his take on Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’s friendly neighbourhood webslinger. That rare sequel which manages to improve on its predecessor, Spider-Man 2 benefitted from its everyman hero, exhilarating set pieces, and a sublime villain in the form of Alfred Molina’s Doctor Octopus, setting the template for countless superhero movies which would follow in its wake. Veering away from the gothic stylings of the Batman films which dominated the ’90s, Raimi leans into the eye-popping colour and earnestness of the source material, and the result is pure blockbuster magic. HW

In terms of the great films of the 2000s, were we to be tabulating a list of great debut features culled from this decade, then David Gordon Green’s ineffably lyrical George Washington would be very much up there. Within the first 10 minutes it’s clear you’re in the hands of someone who has been able to capture a racially diverse group of latchkey kids, all hanging out on the detritus-strewn North Carolina landscape, with a rare and sophisticated sense of naturalism. Much of the film is just spent observing seemingly banal scenes of youngsters at play, until a tragedy befalls the group and their passive (albeit innocent) reaction only makes things worse. DJ

Before starring in Paul Thomas Anderson’s third feature film, Adam Sandler had been written off by most critics as the gurning schmuck from Billy Madison and The Waterboy. His turn as the oddball plunger salesman Barry Egan who falls in love with his sister’s co-worker Lena (the wonderful Emily Watson) changed all that, and established him as a credible dramatic talent. Featuring a sex hotline scam, an airplane miles loophole and the mesmerising works of visual artist Jeremy Blake, it’s a Californian screwball comedy like no other, tender, strange and sweet. HW

Yorgos Lanthimos made a name for himself and modern Greek cinema with a perverse, violent thought experiment about perception, control, and authoritarianism: a father insulates his family from the outside world by fencing them in to their home, where he can tinker with their understanding of language, sexuality, and culture. What could’ve been a big fat metaphor mutates into something stranger and funnier through Lanthimos’ singularly wry sensibility and penchant for sick kicks. (Don’t get too attached to the cat.) CB

It was from the ruins of an intended feature that Miguel Gomes’ second film emerged. His funding gone, the Portuguese critic-turned-filmmaker set off for his location regardless, scaling back his crew and shooting from the hip with the aim of finding out what he had in the editing room. The resulting film is serendipitously inspired in its mischievous design; a rich, metatextual fusing of documentary and melodrama brimming with life and a typically droll sense of humour, while charting a cohesive path to his masterworks Tabu and the Arabian Nights triptych. Matt Thrift

This film was included as a late game surprise feature in competition at the 2006 Venice Film Festival, and many people missed it because it was scheduled so late in the game. And many regretted missing it, because it went on to deservedly win the Golden Lion and brought the work of the then-little-known Chinese director Jia Zhang-ke to a much wider audience. Effortlessly merging elements of documentary and fiction, this tale of a riverside town being demolished to become a floodplain is a reflection on globalisation and how modernisation almost always comes at the expense of tradition. DJ

Edith Wharton’s genius Edwardian novel is a chronicle of the slow but sure fall of the beautiful Lily Bart who dared to pursue independence, rather than a good marriage. Life echoed art as Terence Davies, a fiercely individual artist, was financially ruined by his loyal adaptation. Gillian Anderson is ablaze as Lily, and her embodiment of defiance and despair lights up the screen. Sophie Monks Kaufman

An ailing curmudgeon gets ferried by a long-suffering nurse from one hospital to the next, each one unable or outright refusing to treat the bitter old bastard — but wait, it’s a comedy! Cristi Puiu put the Romanian New Wave on the global stage with his bleakly funny look at austerity in the nation, a subject that necessarily exposed the hypocrisies and ironies of life in Bucharest. And as a bonus, these days, it doubles as a sobering comment on overtaxed healthcare systems. CB

As a maker of hushed, poignant domestic dramas, Hirokazu Koreeda is often asked whether he’s influenced by Yajujiro Ozu, another maker of hushed, poignant domestic dramas. Koreeda often demurs and welcomes the comparison, but often claims to be more in tune with the kitchen sink social realist likes of Britain’s Ken Loach. Yet when you see a film like Still Walking, a contemplative, poetic mood piece in which three generations of a family come together for a feast in remembrance of one of their number’s untimely passing, it’s hard to shake the Ozu comparisons: the gentle humour; the focus on food as a social binder; the profound sense of melancholy that comes from the passing of time. DJ

After a decade-plus of Grand Guignol genre excellence, Guillermo del Toro pivoted to a mossy magical realism and reintroduced himself as an Oscar-winning prestige filmmaker. In Civil War-ravaged Spain, a girl escapes her distressing day-to-day by retreating into a fairy tale with frights of its own, most notable among them the eye-handed ghoul known as The Pale Man. Gold-drenched cinematography, top-flight special effects, and transporting production design wooed Western audiences and conquered the subtitle barrier to attain blockbuster status. CB

Everyone has a different favourite Lars von Trier film, but Dogville is, objectively speaking, his masterpiece. It takes place in a fictional township tucked away in the Rocky mountains, and sees a kindly damsel named Grace (Nicole Kidman) bend over backwards to endear herself to its increasingly fussy and – lol, dogmatic – denizens. It’s a thrilling and, eventually, lacerating civics lesson-gone-awry that is strangely visceral given it is filmed entirely on a blank sound stage with only chalk markings on the floor. Von Trier proves that all you need to make a movie is your imagination. DJ

Mia Hansen-Løve’s second feature marked her ascension to a goddess of cinema. A shocking event is nestled within the hustle and bustle of family life as a film producer faces financial ruin. The miracle here is the weight given to events beyond the central one, causing momentum to fall upon life itself as a forceful flow of time and effort. SMK

Sweden’s Roy Andersson returned from a twenty-five-year feature-directing hiatus to elbow the Grim Reaper in his skeletal ribs once again with gallows humour unmatched for both grimness and hilarity. As Andersson assembles 46 massive still-life tableaux (a ceremonious murder, a bitter sacking, et cetera), death, misery and sadism commingle with comic absurdity in a brutally Brutalist world of greys and beiges. You must laugh to keep from sobbing. CB

While his final film Paprika remains Satoshi Kon’s best-known work – in no small part for having been famously ‘incepted’ by Christopher Nolan – it’s 2001’s Millennium Actress that stands as the animator’s masterpiece. An exquisite homage to a bygone age of Japanese cinema, the film looks back over the career of a reclusive star (clearly modelled on Setsuko Hara), from her childhood discovery to ingenue and starlet, accruing an anecdotal meta-biography through sequences that explicitly riff on real-world golden age classics. At once a reverent and subversive ode to an idealised screen legend, its bittersweet romanticism will cut to the quick of anyone with even a passing interest in one of world cinema’s richest eras. MT

Joanna Hogg’s debut feature announced a thoughtful and distinctive talent willing to go there in terms of showing excruciatingly awkward interactions between monied Brits. Kathryn Worth, a shy woman in her forties, crawls sideways into a mid-life crisis against the backdrop of a friend’s Tuscan villa. She shuns her pals to be with their kids, including a young Tom Hiddleston. The music, once faced, is heartrending. SMK

With Moolaadé, Ousmane Sembène brought the controversial practice of female genital mutilation to the wider film world’s attention, depicting a circumcised woman’s (Collé Gallo Ardo Sy) brave resistance to the ritual in a Burkina Faso village. With great humanity and humour, the veteran Senegalese director unambiguously sets out his stall in opposition to the barbaric act of “cutting” young girls, while eloquently conveying the historical significance of such local customs. A deserved recipient of the Un Certain Regard prize at Cannes in 2004. Adam Woodward

The name Apichatpong Weerasethakul conjures the chirruping of cicadas deep in a green magical forest. His films create an enveloping mood as characters explore their desires in all their strange, shape-shifting forms; folkloric fantasy blending with realism. Tropical Malady is a love story between two men, until the soul of one of them enters a tiger. SMK

Lucile Hadžihalilović’s work is all mood and suggestion. Set in an isolated all-girls’ boarding school (a whole sub-genre in its own right) where new students arrive in coffins. The girls, of different ages, are trained by their teachers to behave, enforce a hierarchy and obey a strict code of conduct. Colour-coded ribbons are involved. A unique combination of fairy tale, horror and melodrama, Innocence is dripping with symbolism. AB

That ending. It comes out of nowhere and leaves you searching online for therapists. Catherine Breillat is not not a provocateur, yet truthfulness underpins the taboo subjects splashed sensationally across her films. Fat Girl is one of her best; on account of its portrayal of teen sexual awakenings, sisterly bitchiness, its shy star’s watchful energy and all-enveloping summer horniness. SMK

An anti-revenge thriller sitting comfortably in the middle of Park Chan-wook’s deeply uncomfortable “Vengeance Trilogy”, Oldboy is a devilish twist on the idiom that those seeking revenge should dig two graves – partly because, Oh Dae-su begins the film by leaving a box, and ends at a much more twisted fate. It’s a far funnier film than its reputation would suggest, mixing tragedy and pitch-black humour from the jump. Kambole Campbell

Published 23 Sep 2020

Part one of our bumper survey of the noughties, featuring Avatar, Borat! and Requiem for a Dream.

Our latest issue is a tribute to the beautiful, unnerving world of Josephine Decker’s biopic that isn’t a biopic.

Our countdown of the finest cinematic offerings from 2000 to 2009 continues. How many have you seen?