Of all the powerful scenes I saw at the cinema in 2023, there is one that has truly stuck with me. It’s not from an award winner, blockbuster, or similar critical darling – the moment occurred during the sports documentary Ronnie O’Sullivan: The Edge of Everything.

Film fans may be forgiven for not having caught The Edge of Everything, not least because it is a documentary about snooker, but also – fittingly for a subject nicknamed ‘The Rocket’ – since it had a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cinema presentation before quickly landing on streaming. As a snooker fan old enough to have witnessed O’Sullivan’s prodigious sporting career in its entirety, it was a must-see for me, yet even entering the film with a solid interest in the subject matter, I was not prepared for the raw and honest truths about mental health that the film would confront me with.

Throughout a career built upon a combination of natural talent and self-disciplined improvement, Ronnie O’Sullivan has been unmatched in the snooker world both in success and duration, winning three major tournaments already in 2024 at the age of 48. Yet despite being overtly transparent and refreshingly honest media presence for over 30 years, O’Sullivan has remained an enigma with a complex public persona.

Common descriptors of O’Sullivan are a mixed bag reflecting different eras, incidents, and appearances. Simultaneously regarded throughout his career as a prodigious yet down-to-earth genius with a rebellious streak by some, and a troubled, disrespectful, entitled loud-mouthed provocateur by others, there has been – until recently at least – an unusual lack of consensus of who Ronnie O’Sullivan is off the felt table.

One thing that has changed significantly since O’Sullivan turned professional in 1992 is his relatively recent ‘G.O.A.T.’ status, breaking and equalling records in the sport to a degree that has made him undeniably the greatest player of all time. Another change over the last 30 years (one that I contend is much more profound), is that both society and the sporting world have collectively wrestled with the concept and importance of mental health.

Sam Blair’s comprehensive documentary effectively outlines the achievements and events that have defined a sporting career, including following O’Sullivan’s run to a seventh World Championship title. But the film also delves deep into the psyche and inner workings of a driven and ambitious yet troubled person. Benefitting from the unfiltered and candid nature that has seen media training averse Ronnie often run into trouble, The Edge of Everything captures a series of raw and honest interviews, fly-on-the-wall portraiture, and intimate sound recordings, and places them alongside archival materials to uncover the man behind the cue.

The complicated and unresolved trauma that followed from his father’s murder conviction at the beginning of his career is shown to have instigated a character change in O’Sullivan, with the resulting turmoil categorised by pundit Clive Everton as a mixture of “depression and rage.” Described further by O’Sullivan himself as a mixture of “self-doubt, and self-sabotage, and hatred towards myself”, these dark times are captured in the tragic response from O’Sullivan upon winning significant prize money for completing the sport’s fastest ever 147 maximum break – described by Stephen Hendry “as the greatest moment in any sport ever” – exclaiming, “Money’s not important to me, I just want to be happy.”

The inherent discomfort and inner turmoil exacerbated by the psychological intensity of his job mixed with addiction issues, anxiety, self-doubt, stress, and depression led to a long and ongoing rehabilitation process. Snooker fans will be long familiar with hearing about O’Sullivan’s love of running and his work with psychiatrist Professor Steve Peters, but here they are shown through an unflinching lens.

When the issue of mental health first explicitly arises in the film, Ronnie pokes fun at the term with a smilingly sarcastic “hashtag mental health” before acknowledging a wider societal change. Where previously his off-the-table behaviour would be remarked upon negatively and scrutinised, now, “all of a sudden it’s cool…I was twenty years ahead of the game, mate.” Deliberately self-effacing, this ambassadorship of openly discussing his own trials and tribulations is described elsewhere in the film by friend Ronnie Wood as “the very noble job of saying how fucked up he is inside.”

The Edge of Everything is able to go beyond typical sporting documentaries because of its unprecedented access, which captures the insecurities, self-doubts, and inner torment in striving to achieve. O’Sullivan’s willingness to allow the filmmakers to document this perhaps highlights a key contradiction in speaking openly about mental health; the unfiltered openness that often leads O’Sullivan into media trouble when discussing the landscape of snooker is also responsible for this admirable vulnerability that makes the film so arresting. Fear of judgement or reprisal often leads to collective silence, and at a time of readdressing the media’s historically cruel and intrusive response to public breakdowns, the film reexamines these moments throughout O’Sullivan’s career with the addition of his own voice and personal context. It shows remarkable resilience that the fear and anxiety captured throughout the film – leading up to O’Sullivan facing opponent Judd Trump for the world title – are so palpable, almost unbearably so.

This culminates in the scene that struck me so deeply. As the pressure alleviates, the film’s score rises, the crowd cheers, and the camera dramatically zooms in to newly-minted champion O’Sullivan’s embrace with runner-up Trump, with John Virgo proclaiming on the commentary, “He’s the greatest player in the world!” However, just as the triumphant moment is set to peak, a radio frequency sound effect signals a switch to a microphone picking up O’Sullivan’s intimate conversations unheard by the crowd and on the television broadcast. As the opponents share a lengthy emotional exchange of mutual admiration, O’Sullivan breaks into a hidden howl of “It fucking kills me!” – a jolting gear-shift from seasoned mentor to a still-struggling soul.

As O’Sullivan embraces his children and hides his face from the crowd, we hear “I can’t do this anymore. I can’t. I can’t do it. It’ll kill me.” The delivery is tortured, and the film’s audio reveals a hidden and heartbreaking tone of the sheer mental toll that the victory and journey have taken on him.

The scene is shocking for many reasons beyond the intentional interference employed by the filmmakers. The scene presents a truth so often not seen or heard in sports viewership and for that matter, in cinema. Aside from revealing a usually shielded moment, it is a shocking disruption that the film’s narrative is not resolved through victory alone, as we are so used to seeing both in fiction and non-fiction.

While it would be naive to not acknowledge that the world of sport at large is dogged by outdated sensibilities, steeped in traditional values and old-fashioned ideals, it has also been an area of surprisingly progressive openness regarding mental health. Alongside O’Sullivan, there has been a growth in the number of hugely successful sports that have been open about mental health issues during or after their career, including Tyson Fury, Dame Kelly Holmes, Jonny Wilkinson, and Simone Biles. However, this is often in the form of interviews or withdrawal from competition, rather than in the heat of the moment. Stigma still exists around admitting mental health struggles while maintaining an athletic career.

Despite having portrayed a person so deeply invested in trying to create their own happiness and overcome their inner demons over a period of several years, The Edge of Everything is unflinching in showing that mental health issues can be and often are ongoing, debilitating, all-consuming, and are not resolved by the successful pursuit of a goal or external moments of victory.

In exploring why this scene had such a powerful, emotionally devastating effect on me that I can’t quite shake, it occurred to me this is something that I’m not used to seeing in cinema itself. While it makes sense to capture this sentiment in a documentary about a sportsperson who has become an unlikely and long-standing ambassador for mental health, is a similar message present in fiction feature films?

As with spectatorship around snooker and other solo competitor sports, there is an inherent human tradition of creating narratives based around competition itself and overcoming adversity, but there also seems to be a deep-rooted tradition of creating hard-hitting sports dramas that are resolved through physical transformation and victory, or just as commonly, loss and tragedy. In this sense, perhaps cinema has fallen behind the actual sporting world in its treatment of underlying mental health issues.

An interesting counterpoint to The Edge of Everything while exploring male mental health in cinema is to see the same scene presented out of context on YouTube with Bill Conti’s ‘Going the Distance’ from the finale of Rocky overlaid. Admittedly O’Sullivan has “gone the distance” of the gruelling tournament, but it is a strange juxtaposition with footage from a documentary asserting that these marathon achievements are also the antithesis of the inner peace he so desperately seeks to find. Its usage is understandable for a standalone clip celebrating the victory but is also perhaps a choice that reveals a wider sense of how intertwined the drama and the anguish featured in both cinema and sport have become.

Cinema narratives are often a reference point for quotations promoting self-motivation and/or working through depression – both Tyson Fury and Anthony Joshua have quoted or paraphrased “The world ain’t all sunshine and rainbows” from the famous Rocky Balboa monologue. This is an understandable source of inspiration for boxers, but it is also one that has pervaded wider self-improvement rhetoric.

The Rocky franchise set the quintessential cinematic sporting precedent with its classic underdog story – on and off screen – with both tales promoting overcoming adversity through sheer determination and will against the odds. Throughout Rocky, Balboa’s insecurities and mental anguish are disguised by an outward happy-go-lucky yet self-effacing charm. The only possible victory for Rocky is to find self-worth through transposing the search for inner peace onto his own physicality, undergoing a transformation culminating in the much-imitated training montage, and ending with a final fight in which it is only possible to sustain or equal a physical beating in the ring with Apollo Creed. The message is one of winning through going the distance, but it is at the risk of losing everything.

It is, of course, unlikely that the film would have resonated so widely or won Best Picture had Rocky solved his issues in a more peaceful way, and the franchise can at least be admired for seeing Balboa repeatedly facing a continuing saga of similar struggles against the odds rather than total self-fulfilment through a fight. However, both the self-actualisation and mutual respect that Rocky Balboa finds with opponent Apollo Creed come only from the life-threatening, unprecedented physical pummelling of an amateur who has upgraded to a world of professional punishment.

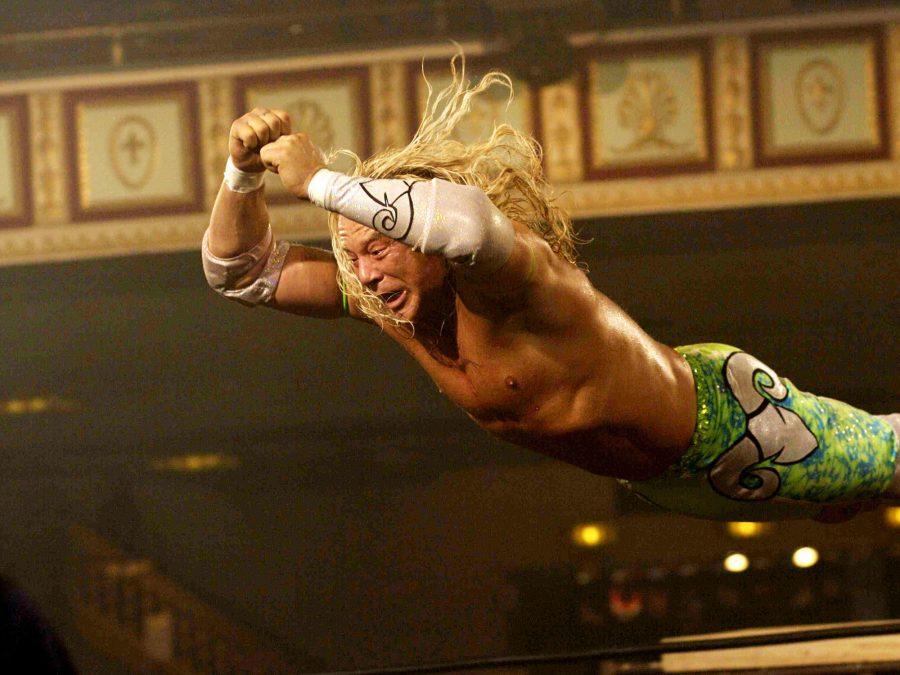

Elsewhere, it is a common narrative that often plays out to more tragic ends. In a fictional depiction of cue sports, Paul Newman’s Fast Eddie is so deeply into the world of gambling in The Hustler that he loses his love interest Sarah to suicide, choosing to continue hustling rather than walking away from the game to be with her. Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler sees Mickey Rourke’s over-the-hill and all-but-forgotten wrestling star Randy “The Ram” Robinson stuck in a demeaning, emasculating job whilst unable to find the emotional ability to reconcile his relationship with his estranged daughter, but instead of choosing to age maturely and face repeatedly trying to confront and resolve the source of his inner turmoil, Robinson opts for certain death by resurrecting his wrestling career one final time.

These readings are not in any way to denigrate these films as at various points I have related to both films in seeking to understand my own mental health issues. I have certainly used Rocky as inspiration to keep going, and have also empathised with the inherent self-destruction of Mickey Rourke’s Robinson. For me, it was somehow easier to see reflected the approach pushing through life’s challenges irrespective of personal toll as some kind of valour, or similarly, to choose solo self-destruction as a preferred alternative route to creating a dialogue. To paraphrase Bruce Springsteen’s original song for The Wrestler, this always saw me leave with less than I had before.

Transposition of mental anguish onto physical pain is taken to new heights in Doug Liman’s 2024 reimagining of Road House, in which Jake Gyllenhaal plays Elwood Dalton, an ex-UFC fighter tormented by memories of killing a former friend in the octagon and subsequently leaving the sport altogether.

Taking up the position of an (unusually slow to respond) security manager at The Road House bar, Dalton is initially calm and favours conflict resolution yet is still willing to use his mental Rolodex of cruel physicality to disarm an enemy. Seemingly unable to feel pain, or at least carrying it as the trope of physically wearing your emotional baggage, Dalton’s only Kryptonite is the memory of killing his friend.

‘The Love of a Good Woman’ is an often necessary part of the formula to produce instant cinematic on-screen recognition of masculine equilibrium and stability. In Road House, love interest Ellie is a confused mixture of archetypes thrown at the wall: ‘the worried caregiver’ meets ‘damsel in distress’ meets ‘independent woman’, although this is still preferable to ‘the dead wife’, ‘the missing daughter’ or ‘the woman he genuinely loved that double-crossed him’ as the alternative route of instigator for an action plot.

Regardless, Gyllenhaal’s Dalton reaches a new height in cinema for a man who cannot be open about his emotional issues. Even when the film has concocted a scenario in which Dalton is entirely alone in the middle of an open body of water with Ellie he is unable to open up about his past. This creates an unusually surreal exchange between the two isolated characters:

“So, where are you from?”

[4-second beat]

“Me?”

Dalton is suddenly too vulnerable, preferring to deliver the “you don’t want to know me” line instead of talking about his past. Ellie’s Adrienne-esque character persists in trying to save Dalton despite this and of course, is rewarded by being kidnapped as emotional capital, all so Dalton can have a narratively acceptable emotional breakthrough and more importantly for the film, a justification for violence.

Dalton ultimately deals with his mental pain and trauma of killing someone by…killing a lot more people. He finishes off the Bad Guys™ with no repercussions before hopping on a Greyhound bus to disappear. So goes a male fantasy oft repeated throughout cinema history: the strong, silent, invulnerable hero that saves the town, smashes and crashes, hits and quits, and goes from zero to hero in under two hours.

The separation between fantasy and reality is something most audiences do not struggle with, but it is another link in a chain of a more insidious underlying narrative of masculine trauma response in film, rewinding from the original 1989 Road House through action movies to Bond to Westerns, right back to the inception of cinema. It has created a language – or lack thereof – of dealing with feelings, grief, trauma and depression with actions, and not words. If stories do indeed form part of our self-identification and provide motivation, where other disciplines are learning to talk about mental health, could the cinematic lineage of the strong, silent type be seen as archaic? Further, if cinema is part of our collective psyche, is the portrayal of equating the overcoming of mental adversity with victory (and often physical violence or sacrifice) setting a flawed precedent for addressing inner turmoil?

Although The Edge of Everything stood out to me for its honest depiction of actual conversations around mental health, it also provided a familiar, aspirational victory narrative; let’s not forget that Ronnie O’Sullivan is a hugely successful sports star. Yet the open discussion is refreshing, both to camera and in candid moments, and victory comes without familiar monologues of self-pity and revenge.

Even in the films I have most admired that depict men’s emotional suffering in recent years, there is still a lot that men do not seem able to say on screen. This is a reflection of the traditional male pride and famous inability to open up that many men experience, myself included and various films have captured this suffering in silence, such as Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun and Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy. This honesty is part of what makes both films so affecting, and in their respective, powerfully emotional finales, both Paul Mescal and Will Oldham walk away, tragically unable to admit just how much trouble they’re in.

This is not to suggest that storytellers should create films with convenient happy endings or drama-less arcs, but as someone drawn to these issues, it still feels taboo to see substantial male dialogue on these issues on screen unless it’s played for laughs. The profoundly lost character is instead often left to dissipate. Therein lies an uncomfortable challenge for the fiction feature film in the modern age, particularly in genres that often fixate on the external, the transformative, and the triumphant. How easy or appealing would it be to create and sell an oppositional work of film that articulates internal struggle or wider invisible illnesses in a non-catastrophic way?

Much modern discourse on cinema is rightfully focused on onscreen representation and I found this, somewhat unexpectedly, in The Edge of Everything. The raw and intimate depiction of a person on the edge of breakdown was a meaningful mirror for me, and perhaps the closest I’d seen my own experiences of depression, anxiety, burnout, stress, and the pressure of just trying to get somewhere. Even though I am admittedly a terrible snooker player, the emotional representation was immensely powerful to me.

Every day people pour their blood, sweat, and tears into achieving their goals and/or just simply getting by. To continue with sporting analogies, it is often the norm to leave everything on the field. We become trapped in a high-risk, high-reward cycle of survival in an enforced competitive environment, whether we like it or not: from school and good grades to jobs, interviews and performance reviews, side hustles and long hours, external comparisons and self-scrutiny, finding meaning or some kind of inner peace, and just the whole general providing, thriving, surviving thing. Even in our most basic lives – the lives that sit outside of the extraordinary tragedies and traumas that the world presents – getting through life is a marathon.

O’Sullivan is an advocate for continuous and holistic self-improvement. Although it is a familiar cinematic narrative to see a male character reach the peak of their physical skills and abilities to overcome adversity, or otherwise disappear into avoidance and the quicksand of self-destruction to tragically succumb to it, it is refreshing to see a documentary subvert and tackle these familiar themes with a realistic, human vulnerability, and a focus on the importance of addressing mental strength rather than solely physical prowess.

The victory arc of The Edge of Everything is not what the filmmakers highlight as O’Sullivan’s major career triumph; what the film commends most highly is his commitment to an ongoing formula for survival. Unlike fiction feature films, its conclusion is neither tragic nor wholly victorious. Despite winning, there is a sense that the true battle continues and despite breakthroughs and resolutions addressed within the film, including O’Sullivan overcoming addiction or finding peace with his complicated relationship with his father, these things are by no means signalled as solutions to underlying difficulties.

In the epilogue, which sees O’Sullivan laid on a bed in a deliberately confessional fashion, the finale of the film sees a final expletive-laden impassioned outburst of victory, which seems to be a triumph over the sport itself, rather than within it. Ronnie exclaims, “I’ve taken control of my life and that is it, the most important thing is that I’m happy”. He outlines a refreshing unwillingness to no longer endure a continual beating from his line of work as a route to meaning, instead choosing to navigate it in a way that will offer personal happiness and contentment.

This epiphany comes from the intentionally therapeutic reflection employed; a revelation that surprises even O’Sullivan who expresses that he doesn’t know where it came from. In choosing to end here, The Edge of Everything is a statement on continuing conversation, on the importance of words and self-work in looking to find long-term acceptance and existence, where a freeze-frame Rocky ending only provides a temporary solution. If fiction features continue to push narratives mostly resolved through climactic violent action or tragic consequences, it could be offered as a logical conclusion that there is little self-identification for those who don’t seek either of those options.

At a time when the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions has proclaimed that “mental health culture has gone too far” and that “as a culture, we seem to have forgotten that work is good for mental health”, it seems more valuable than ever to have openly candid representations of the realities of mental health on screen. The sinister undertone of such statements is that for people living with mental health issues, it is simply a lack of resilience that is the real problem – itself an “it’s not all sunshine and rainbows” fallacy.

Public representation and open conversation are a necessity if such cruel, misinformed attitudes are ever to change. For those of us who scream internally, “I can’t do this anymore. I can’t. I can’t do it. It’ll kill me” but have been long led to believe that we should keep getting hit and keep moving forward despite this, The Edge of Everything at the very least provides an alternative role model in Ronnie O’Sullivan.

Published 30 Apr 2024

By Nora Murphy

Emma Seligman's Bottoms promises a queer female fight club – how does it perform in the canon of films about women carving out space for themselves in hyper-masculine worlds?

Through conversations with psychologists, neurodivergent friends, Jason Schwartzman and the man himself, Sophie Monks Kaufman investigates the meticulous worlds of Wes Anderson and their potent emotional frequencies.

Within the gentle, naturalistic films of Kelly Reichardt, domestic animals are granted the space to exist as they are – not as performers, but as companions.