The prodigiously talented Inherent Vice director reveals what makes him tick.

Paul Thomas Anderson doesn’t know Thomas Pynchon, so stop asking. Just because the famously reclusive author finally allowed one of his novels to be adapted for the screen doesn’t mean that he was willing to step out of the shadows. According to Anderson, the two of them never so much as spoke on the phone. It’s tempting to think that the director might be stretching the truth in order to protect his new pal, especially when credible rumours persist that Pynchon appears in Inherent Vice as an extra. Anderson maintains that the two remain perfect strangers.

“I don’t know Thomas Pynchon; I don’t know who he is, I don’t know what he looks like. I didn’t consult with him on the script. That’s all I’ve got to say. I really feel like he’s like B Traven. Remember B Traven? The guy who wrote The Treasure of the Sierra Madre? He was this kind of shadowy figure who would come drop pages on John Huston’s desk. I don’t even know if anybody else asked [to adapt one of Pynchon’s books] and he said no. I know there have been rumours that somebody wanted to make an opera of ‘Gravity’s Rainbow’ and Pynchon declined, things like that. But this book leant itself to adaptation more than the others.”

Anderson has said that he thought of himself as a surrogate for Pynchon’s novel, and the fidelity of his adaptation bears that out. Nevertheless, it’s hard to imagine how the film would have worked without one crucial change that Anderson made to the source material. Sortilège is just an incidental character in the book, but he couldn’t help but latch on to Pynchon’s observation that, “She was in touch with invisible forces and could diagnose and solve all manner of problems.” So he promoted her to narrator, cast faerie-like musician Joanna Newsom in the role, and shot her in such a way to suggest that she could fathomably be a figment of Doc’s imagination.

“The spectral dimension to her character is not even really by design. By hiring Joanna Newsom, you’re hiring this kind of flesh-and-blood ghost who’s clearly been living in many multiple eras over time. She just has that about her, that’s what she brings to it just by being there. Something about her is so elegant, beautiful, and knowing. She’s, like, from another planet.”

Sortilège’s promotion might be the most significant change that Anderson made to Pynchon’s novel, but that wasn’t the only thing he felt compelled to tweak. The story of ‘Inherent Vice’ is perched at the precipice of late-stage capitalism, and while the film nails the book’s bittersweet tone, it offers a slightly more optimistic view of the future than was offered by Pynchon’s prose. Or not. “I felt like the book was more optimistic,” explains Anderson. “Way more optimistic. The ending of the book, where he’s hoping that the fog will burn off and that somehow, something will be there this time, instead… that’s hopeful and optimistic. I think the feeling ultimately is the same as the book. And that’s the trick of that book, being never-endingly pulled in two directions. It’s pissed off about being sad, and also sort of bitter about being sad. And also just sad about the way things turned out, but never losing that sense of humour.”

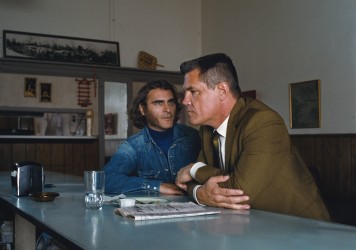

Anderson has always been loyal to his actors, and he loves to show new sides to old faces. Inherent Vice is only his second collaboration with Joaquin Phoenix, but Freddie Quell and Doc Sportello are such feral and fully realised characters that it already seems as if theirs is already one of cinema’s most potent creative kinships. Yet Anderson insists that their shared experience on The Master didn’t make Inherent Vice any easier. “You get to know each other over the course of the movie, so there’s a comfort there. I mean, we were pretty comfortable working together on The Master. But when you’re faced with a whole new set of problems, you might as well be starting from scratch. It’s no less confusing or scary. You’re no less insecure or searching for some kind of confidence somewhere, from something going well. And then when you do, you get lucky for a couple hours, if that, and then you’re right back down to wanting to kill yourself. And then the movie gods come along and give you something good, and it’s like that, over and over again. Whatever movie you made before with somebody is like a distant memory.” He continues, “I think you sometimes hypnotise yourself before you start a movie and think, ‘This will just be nice and fun and easy to go and make.’ Which is just a way of convincing yourself that it won’t be as difficult and challenging as it always is. If anything, it’s about finding ways to talk myself out of doing it. That’s what you spend more time doing. But we were just trying to do the book.”

It’s strange to hear Anderson doubt himself. He may not exactly be an outspoken egomaniac, but his myth is predicated upon a careful balance between determination and hubris. This is the same guy who, as a 23-year-old PA on a PBS movie starring Philip Baker Hall, approached the actor with a script he had written for a short film. This is the same guy who made a star-studded porn epic when he was 26, and followed that up by getting Tom Cruise an Oscar nomination for yelling “Respect the cock!” Maybe Anderson has just come to grips with his own limitations, but he’s hard-pressed to remember a time on the set of Inherent Vice when he was confident that the movie was going to work out. “You’re just trying to get through the day, or the hour, or the scene, or whatever… I’m trying to remember what it was that for a few moments gave me some excitement. I don’t want to embarrass him, but when I saw Joaquin get dressed I felt pretty good. But that didn’t last for long, because then you’re on a set and you say, ‘Well that’s not right!’

“I remember having a day that was really good… he was deep into it. I remember this small thing when he was looking out the window. That was just a great memory, because it was one of those things where you instinctually came up with an idea and you just did it, and you did it quickly. You didn’t run it into the ground, and you got out before you ruined something, which can happen often happen. Like staying way too long at the party… Ultimately those are the scenes that don’t even make it into the movie, and you don’t know it at the time. You think you’re doing something wrong, but really it just doesn’t belong in the movie. And normally scenes that do go relatively smoothly are well written and they’re simple to shoot. I don’t mean that you don’t have to put work into it, but you’re lucky to get a few of those days. And you need them, because other days will be struggles.”

Of course, Anderson has learned a thing or two over the years, and Inherent Vice finds him leaning hard on his favourite tricks. A hippy handshake between the restlessness of the giddily overstuffed ensemble pieces that put him on the map and the sedation of the piercing character dramas that have made him a legend, Anderson’s latest has a style all its own. But ever since production photos revealed an absurdly long strip of dolly tracks down the California coastline, Inherent Vice has promised to underscore the director’s affinity for long takes. “I think when you show up to work each day the goal is, ‘How can you make this just one shot?’ because when you have to edit it together, it requires way more attention to detail than you’d think. You have to match things and do it over again, so it’s best if you can just get two people in the scene talking and it can be more fun because you’re just going after that one thing. It gets you concentrated and it can be effective. I like not having to edit. If you can get two good actors in the same shot then you can watch them both and you don’t have to choose where you’re looking, you can let the audience decide. It’s instinctual moment to moment or scene to scene. It’s simple and nuts-and-bolts stuff, it usually doesn’t have any larger design behind it.”

A film school dropout, Anderson is a hardcore cinephile who’s reluctant to explain any sort of intellectual motivation behind the choices that have shaped his career.

Nevertheless, his encyclopedic knowledge of classic American noir was actually something of an obstacle for Inherent Vice, even if it meant he didn’t have to do his homework. “I mean look, those movies were familiar to me. I didn’t have to go back to them at all, they’re ingrained in my mind. But I did get out The Big Sleep again just like, ‘Oh, let me remember that,’ and it was incomprehensible and that was okay. If anything, it was like trying to shake off those movies in a very respectful way. Those would be reasons not to make the movie. But looking at those things, looking at those devices, I brushed up on that a little bit. Those movies are in my DNA, they’re in my pocket. I didn’t need to see The Long Goodbye for the four-hundredth time. If anything, I needed to try to forget it.”

Even if Anderson was determined not to repeat the past, his influences clearly remain his first language. And even if older movies weren’t super helpful in making Inherent Vice, they’re clearly his favourite way of thinking about it. Asked about Jonny Greenwood’s score, and the righteous selection of surf rock classics that surround it, Anderson defaults to Albert Brooks. “Have you seen the movie Modern Romance? Where Albert Brooks is the director, and he’s the most neurotic director, and after the screening he’s like [does Albert Brooks impression]: ‘I know they’re going to say that there’s wall-to-wall music, but I like the score!’ That’s exactly how I feel right now. I think it’s important to always be conscious of the music, like, ‘Is there too much of it? Is it out of the way, is it helping, is it okay?’ And hopefully you land in a good spot where it is quiet from time to time. But yeah, there is a lot of music, helping push the story along. But the score was a little more important to us than the songs. Hopefully, at its worst, it can just feel like a jukebox playing top 10 hits. But being able to play ‘Journey to the Past’, it’s good to hear that song. It’s a beautiful, beautiful song, and that’s a version that’s not often heard, so it was great to get that in there. Same thing with ‘Harvest’, same thing with all of it. The Minnie Ripperton song ’Les Fleur‘, which is great and by Maya [Rudolph]’s mom, and the Chuck Jackson song ‘Any Day Now’. Any time you can get some Neil Young in there is a good feeling.

“The book was so filled with musical references, and we used some of them. ‘Here Come the Ho-Dads’ was sort of earmarked from the book for when Doc goes up to Topanga Canyon, and that’s a great surf song by the Marketts. But the others sort of fell away. I thought they’d be used, but they ended up not exactly fitting in. I’ve always wanted to work with Can’s ‘Vitamin C’. It has been used here and there before, so you have to get past that a little bit and realise, ‘It is gonna fit well here, it’s gonna be okay.’ I mean look, there’s no reason why an Asian-German lead singer and three white German guys should play that funky. Nothing that funky is coming out of Germany!”

Speaking of influences… “What’s that thing they take in Fear and Loathing that he’s only supposed to take a drop of, and he ends up drinking a lot and Benny [Benicio Del Toro] is like, ‘How much did you take?!’ Ether? I gotta get my hands on some. And you see his face start to turn into a lizard. Mescaline, yeah. To be honest, I didn’t really think that much about the drugs in the story. It was like wearing a hat or wearing sunglasses, it wasn’t really too much of a thing that we thought about or talked about.”Anderson may have started off being hailed as the most prodigiously talented wunderkind since Orson Welles, but whip-pan to the present and the 44-year-old family man is seen as a bastion of the old guard.

In part, that’s because his films are afforded a reverence usually reserved for the auteurs who first defined the cinematic legacy of the American epochs that Anderson depicts. And in part, it’s because he rose to prominence just before film became a terminally ill shooting format, and has remained loyal to celluloid ever since. But Anderson doesn’t seem to share the same hostility towards digital that inspired Quentin Tarantino to say, ‘Why an established filmmaker would shoot on digital, I have no fucking idea.’ Anderson isn’t scared of the future; he’s just scared that he wouldn’t know how to use it. “I don’t know, because I don’t know much about those cameras. I know that’s been a complaint, but I wouldn’t know. Film is what worked for this film. I have a fear of the unknown. I’ve spent a long time trying to learn one camera, and to fucking stop and try to learn another one… I would have to stop for 20 years! I’m a slow learner; I’d have to go through the manual… it would be starting over. So there’s that, too.

“It’s an issue for filmmakers, and it’s on people’s minds, and I have to say that it’s a lot more challenging and difficult just to kind of get somebody to show film or to print film. It’s far more challenging than it should be right now, and we’re just trying to keep it alive a little bit and create a little pocket where it can be shown that way in various places across the country right now.”

Save for perhaps Punch-Drunk Love, which exists in the sweet synesthesia of its own dimension, each of Anderson’s films is a time capsule, a period piece, or both. With each successive feature, it grows ever more tempting to re-arrange his features by the chronology of their stories and look at his body of work as an alternate history of 20th century America. Anderson may not see much value in such an exercise (“Fuck. I mean, that would be cool, I guess. That would be wild!”), but his films nevertheless evince an uncanny ability to recreate the past so that it feels ineffably present. Inherent Vice exists within a smoked out snow globe of Manhattan Beach as it was on the doorstep of the ’70s, and the movie would never have worked if not for the perfect bubble that Anderson and his team built around it. When it comes to convincingly traveling back in time, Anderson swears that less is more. “I kinda grew up in an era where I started to notice that period pieces would have too many unnecessary crane shots. I was like, ‘Why are there so many establishing shots of streets?’ I think I kinda got it into my head that if you weren’t striving to sell that it was a period film then you probably wouldn’t do those.

“I don’t know, I think I was just reactionary to that stuff, trying not to think about it too much. And honestly, nobody cares about anything but the people, anyway, that’s all they’re looking at. They’re not really looking at the storefronts or your gigantic city streets. I have to say, when you don’t have any money, that’s where you come up with those justifications. You’re like, ‘I can’t fucking do a street shot, I don’t have the money! Why don’t I point the camera at the actors and make a close-up?’ Unmotivated crane shots are a sin.”

In America, money is everything. In film noir, money is everything else. The true value of The Maltese Falcon, for example, has less to do with its worth than it does the price that someone is willing to pay for it. As Inherent Vice coheres into a surfer rock elegy for the things that money can’t buy, it’s the story’s unifying concern that most palpably cements the bond between the film and its genre roots. You might think, deep into a career in which all seven of his features have had a seismic impact on the cinema and its surrounding culture, that Anderson could trade anyone in Hollywood a new script for a blank check with his name on it. Even if his movies are not always runaway hits, they’re always critically acclaimed. That’s got to be more important, right? “No, the dough is more important.”

Published 29 Jan 2015

Paul Thomas Anderson charts the end of the hippy dream in this blissful gumshoe chimera.

What Jonny Greenwood did on his holidays makes for rousing cinematic statement.

The star of Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master discusses his special relationship with his long-time friend and collaborator.