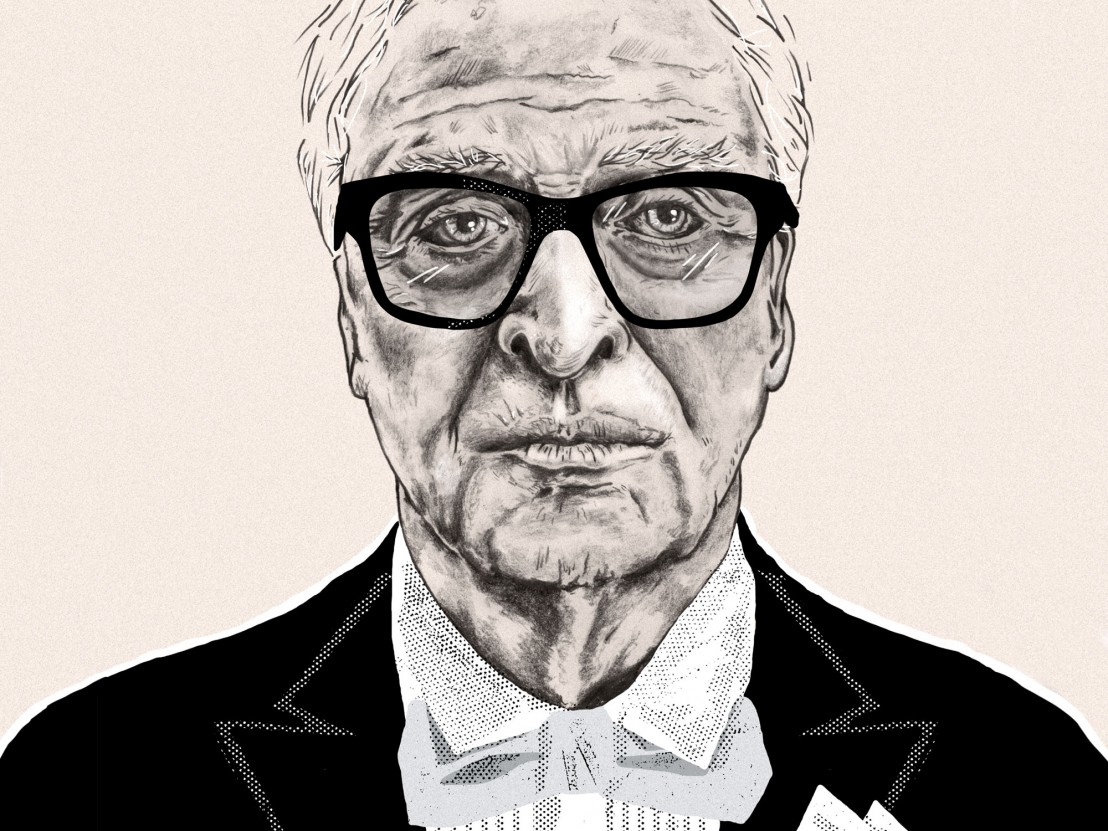

The British screen icon reflects on his remarkable career ahead of his starring role in Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth.

Michael Caine is propelled by such perky charm that everything he says – in public life or within character – seems peachy. It often isn’t as simple as that, but such is the power of his unique persona. His voice is immediately recognisable, a blend of cockney chancer and man of the world. Film-wise, he has starred in the great and the good, the bad and the awful, albeit without ever personally delivering a duff performance. Caine is a consummate professional whose attention to craft began when, at aged 14, he took out a book on acting technique by the Russian actor Vsevolod Pudovkin from the Southwark Public Library. “Film acting is re-acting, not acting” and “never blink before the camera” are self-taught lessons still evident in his performances today.

Caine has been through a lot, on and off screen. He is open to the point of pride about his upbringing among the poor, working classes of south London. He was part of the evacuations during World War Two, and in 1952, national service took him to Korea for two years. From there, it was full steam ahead into the world of acting. His eyes were always on the movies as he slogged away in theatre and then in television, absorbing advice from colleagues and mentors at every opportunity. His first film role finally came in 1964 with Cy Endfield’s Zulu.

“His name is Michael Caine and no one will forget his name: Michael Caine. He walks straight into sensational stardom in The Ipcress File, as he gets right under the skin of the brash, cocky, wry-humoured Harry Palmer.” So announces a clipped voice in the 1965 trailer for Sidney J Furie’s 1965 film The Ipcress File, propaganda which would prove to be prophetic. In 1966 along came Alfie and the essence of Caine’s ability to make the camera love him as a rogue.

He refers to women as “it” and, miraculously, remains adorable. He reached America in the same decade, starring opposite Shirley MacLaine, who personally sought him out for a role in Ronald Neame’s Gambit. It’s been a full 50 years of A-game work in Hollywood and back home in the UK, across serious drama, slapstick comedies, genre films and arthouse gems. He has worked as favours for pals, for the high-life and for the love of acting. Caine enjoys telling movie star anecdotes.

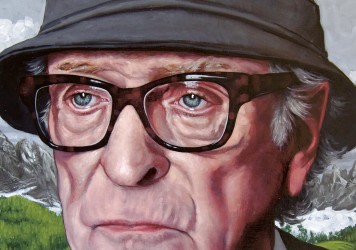

The span of his career means there’s gold at his fingertips on the likes of John Wayne, Jack Lemon, Cary Grant and Bette Davis. He has worked for with Brian De Palma, Woody Allen, John Huston, Joseph L Mankewicz and Alfonso Cuarón. Christopher Nolan basically won’t make a film without him. He is comically alive to the sweeteners of location and famously agreed to act in Jaws: The Revenge after seeing on the first page of its script the words, “Fade in: Hawaii”. This shoot meant he was unable to accept his Best Supporting Actor Oscar for Hannah and Her Sisters, in which he is sublime – adding heavyweight pathos to Woody Allen’s flyaway New York.

Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth adds another rich role to the canon. Caine plays Fred Ballinger, an elderly, retired composer who now resides in a luxury Swiss resort. Here he shoots the breeze with his director friend, Mick (Harvey Keitel), and rings in the changes that come with age. It becomes apparent from the arrival of his daughter, Lena (Rachel Weisz), that Fred has not always been a loving father. Caine makes him a success and a failure, a comic presence with tragic burdens. When LWLies met with Caine after Youth’s premiere at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, he was willing to talk about his family, his friends, his memories… every bloody thing.

LWLies: Do you have to stave off the memory loss that can come with ageing?

Caine: No. I spent 60 years remembering dialogue. What happens is, as I get older, I don’t forget it but it takes me 10 times longer to learn the bloody thing, that’s where the mental thing goes. I used to look at the script to go “okay”. They’d give me a page of dialogue and say, “We shoot it in 20 minutes.” They give me a page now and I say, “We’ll shoot this next week.”

Fred and Mick talk about wishing that they could remember specific event in more detail. Can you relate?

No. I have a memory like a computer. I remember every bloody thing. Oh, it’s dreadful. I have a memory so full of stuff that I wish I could get the garbage guy to come round and clear some out.

When did you first know you had a good memory?

Always. But my best friend died of dementia. What’s it called – not dementia – Alzheimer’s. It’s like watching someone walk away to the horizon very slowly. It takes them three years to get out of sight and then they’re gone. I remember going round his house. I came in and he didn’t know who I was for the first time, the very first time. He was my tailor actually. His name was Doug Hayward.

How did it affect you?

I started looking up books which tell you what to eat. You know you get all of those pills? I’m a bit too old for them. I’m 82. I think, “You’re so old dementia says, ‘Forget it.’”

Fred and Mick’s friendship is rooted in only saying nice things to each other. Is that also your concept of friendship?

Oh yeah, I’ve never said anything nasty to my closest friends. I have 11 closest friends. I was sitting someplace very lonely on location in Africa, and I thought, “I wish my friends were here,” and then I counted them. I have 11. I have about eight now. Three are dead. But none of them have I ever had a row with. We never say things like, “You’re great and you’re fantastic but you know what’s wrong with you?” We never say that. Nothing’s wrong with you. Nothing.

Are any of them people we might know?

One of my closest friends is a composer called Leslie Bricusse. He wrote ‘What Kind of Fool Am I?’ [from Stop the World – I Want to Get Off] He wrote millions of songs. He’s one of my closest friends and we’ve never said a bad word. We’ve known each other 52 years.

You seem to be very loyal. You used to be the womaniser who was playing Alfie, and you’ve had a marriage of nearly – what is it? – 50 years?

46.

What’s the secret behind that? Keeping old friendships and keeping your very best friend, your wife?

All of my friends got married. We were all chasing girls when we were young and then we all got married at about the same time. We all married very happily, and none of us ever got divorced. Oh, wait, I got divorced. I got married when I was 20 and divorced when I was 22, which is usually what happens if you get married when you’re 20.

But if you’re a movie star, there are the opportunities.

Yes, I know that. But the first thing I did was I married the most beautiful woman I’d ever seen in my life. I still mean that. And we always go on location together. Location is the tricky part, because some actors say location doesn’t count, in their marriage. Everywhere counts in my marriage.

Have you ever had the feeling that you neglected your children because of your career, like Fred does?

No, they used to come on location with me if it was good. Everybody always travelled with me everywhere: the whole family. For instance, I’m going to do a movie in New York in August and I’m not staying in a hotel room. I’ve got a house with a swimming pool and a tennis court. The grandchildren, their nannies, everyone is coming. I travel with the whole bloody lot.

Do you dote on the grandkids now?

Oh, the grandkids, don’t get me started on them. I’ll bore the pants off you for six hours. I had two daughters, and my first grandchild was a boy and he looks exactly like me only better looking. I didn’t know the other two were coming, the twins. They were later. But this boy became my son and, to this day, is my son in my mind. I’m one of his fathers. He’s got two fathers. We were watching a cartoon together one day and a commercial for Batman came on, one of my movies. I’m standing there with Batman, and he looked at me. He didn’t know I’m an actor. He was about four. He said: “Do you know Batman?” I said, “Yeah, he’s a friend of mine.” And he told everybody. He stood up at school in the class and said, “My pa’s a friend of Batman’s.”

There’s been a lot of caricatures of you, like The Dork Knight.

It’s a compliment. People say to me: “Do you get annoyed at people stopping you in the street?“ I say, “Not as annoyed as I’d get if they didn’t stop me in the street.”

How would you describe Youth?

This film is about life. It’s funny, it’s sad, it’s everything. It’s not a comedy, it’s not a drama, it’s not a satire. It’s not a musical, but there’s a lot of music in it. It’s Paolo, that’s what it is, Paolo’s view of things and I love it.

What sense do you make of the outrage of the actress (Jane Fonda) towards the director (Harvey Keitel)?

I was trying to figure out who she was based on. I think it might have been Bette Davis or, I’ll tell you who: Joan Crawford. I never knew Joan Crawford but I knew Bette Davis. Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy were friends of mine from New York theatre. One night I was in New York on my own, publicising a movie, and they said, “Come out to dinner with us.” I said yes. They said, “We’ve got you a date.” I said, “Okay. Who is it?” It was Bette Davis. We had a great evening together. I was about 40, she was about 75. At the end of the evening she says to me: “I am going home alone in a taxi.” Just in case I was gonna make the first move.

How was shooting the scene with Miss Universe?

Well that was awkward because the water wasn’t there. That’s CGI – that was put in later. The platform that you see is their platform that they use. That’s the way you get across the square when it floods. But the most awkward thing for me was when I got to the other end I had to drown. I had to drown with no water and everyone’s going “What the hell?” I’m doing this standing on the platform that’s in St Mark’s Square. I was very happy when I saw the movie because I’d never seen it with the water and the lights and everything. I thought it was fabulous the way it looked.

But Miss Universe wasn’t a special effect?

No, oh blimey no. She’s not is she? She’s incredible. Beautiful. Something reminded me of fast prejudice. I loved the girl, I thought she was a smashing girl. She did the nude scene and everything. Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful. I thought, ‘She’s wonderful.’ Then she had this long scene, screaming and lots of dialogue. And I thought, ‘Oh shoot we’re gonna be here all night. She’s gonna screw this up.’ She did it in two takes. You see, what’s great about her is she can really act this girl. And she’s a lovely girl.

What was it like doing a nude scene with Harvey Keitel?

We kept our clothes on. We don’t want to upset anyone. Nobody told us about her. Paolo didn’t tell us. We were just sitting there in the pool. He said we’re just sitting there relaxing and then someone will come in the pool – a pretty girl’s gonna come in the pool. He didn’t tell us she was nude. We thought the pretty girl was gonna come in a bathing costume, you know, and we’re gonna be like dirty old men standing there. That’s why you’ve got the stunned look on their faces.

Which actor has most influenced you and why?

Humphrey Bogart and Marlon Brando. Humphrey, because he could talk like an ordinary human being. I know he was supposed to be a tough guy, but there was a reality to Bogart which a lot of others didn’t have. And Brando because he was such an incredible actor. He wasn’t just standing there, he would do all sorts of things. I found out that he couldn’t remember his bloody lines. He used to have them on the wall everywhere. I wish I could’ve done that. I met one actor who said that Brando typed his lines on his forehead. I thought, “It’s a good job I wasn’t an actor then, he wouldn’t have got away with that on my forehead.”

Bogart and Brando were from modest backgrounds, which was possible for American actors earlier than in the UK. Do you think you were part of a working-class breakthrough there?

Yeah, I was one of the first ones, but that’s not conceited because I didn’t do it, the writers did it. I was very fortunate to become an actor, when the writers came along. For instance, the British screenwriters never wrote war stories about private soldiers. Only Americans wrote war stories about private soldiers. They didn’t write about officers, the British wrote about officers. They wrote about the middle-class all the time, until John [Osborne] came along and wrote ‘Look Back in Anger’, which was the first time there had been a working class person in the lead. And Noël Coward wrote one too. Then there was a play called ‘The Long and the Short and the Tall’, which – in the theatre I’m talking about – made Peter O’Toole a star. He gave a fabulous performance in that play. I was his understudy and I took over when he went to do Lawrence of Arabia. And that was the first play ever about private soldiers.

Has production begun on Going in Style with Alan Arkin and Morgan Freeman yet?

I started that on 3 August in New York. Alan Arkin, Morgan Freeman and me are three old guys. The bank forecloses on the mortgage on our flat and we can’t pay it. So we rob the bank. And that’s it. The three of us rob the bank.

Do you think there is a conflict between youth and old age? In your 2009 film, Harry Brown, there was a moral conflict between the old and the new generation.

I shot Harry Brown where I come from. I could see where my house used to be. We were bombed out in the war and then they made these pre-fabricated houses with asbestos. We used to live in those. Which, funnily enough, was a lot better: we had a bathroom, hot water running, everything. And they pulled it down and put new flats in, council flats. I was working there with these guys. One thing that had changed about it was racially. When I grew up everyone was white. Now it’s 50-50 black-and-white there. But they’re all the same, and they’re all tough. What had changed was drugs. We used to get drunk and have a fight. Now it’s drugs and they’ve got knives and pistols. There’s a lot of money in it. I used to sit down with these gangster guys, gangs, really scary people; but not me because I am them, so there was no reason for me to be afraid – and every time I sat down with a new lot they’d say, “First question: How did you get out of here Michael?” I felt so sorry for them.

“You get an Oscar, it’s for a performance. You get a knighthood, it’s for a life.”

How did you get out?

I went in the army. Prince Harry has just said something that I agree with: bring back national service. In England we served in the army for two years. And I did it. And you don’t have to do two years like we did, and you don’t have to go kill anyone like we did. Just six months of army training and discipline. Then you come out feeling that you deserve to live here because you’ve trained to defend this place, should someone come. It’s a thing of loyalty and I think it would be very important. When I came out I was one of the last lot to do national service in 1953. I watched the younger generation and they changed. The generation that made the ’60s were the ones who’d been in the army. The ones who made the ’70s were the ones who went into the drugs.

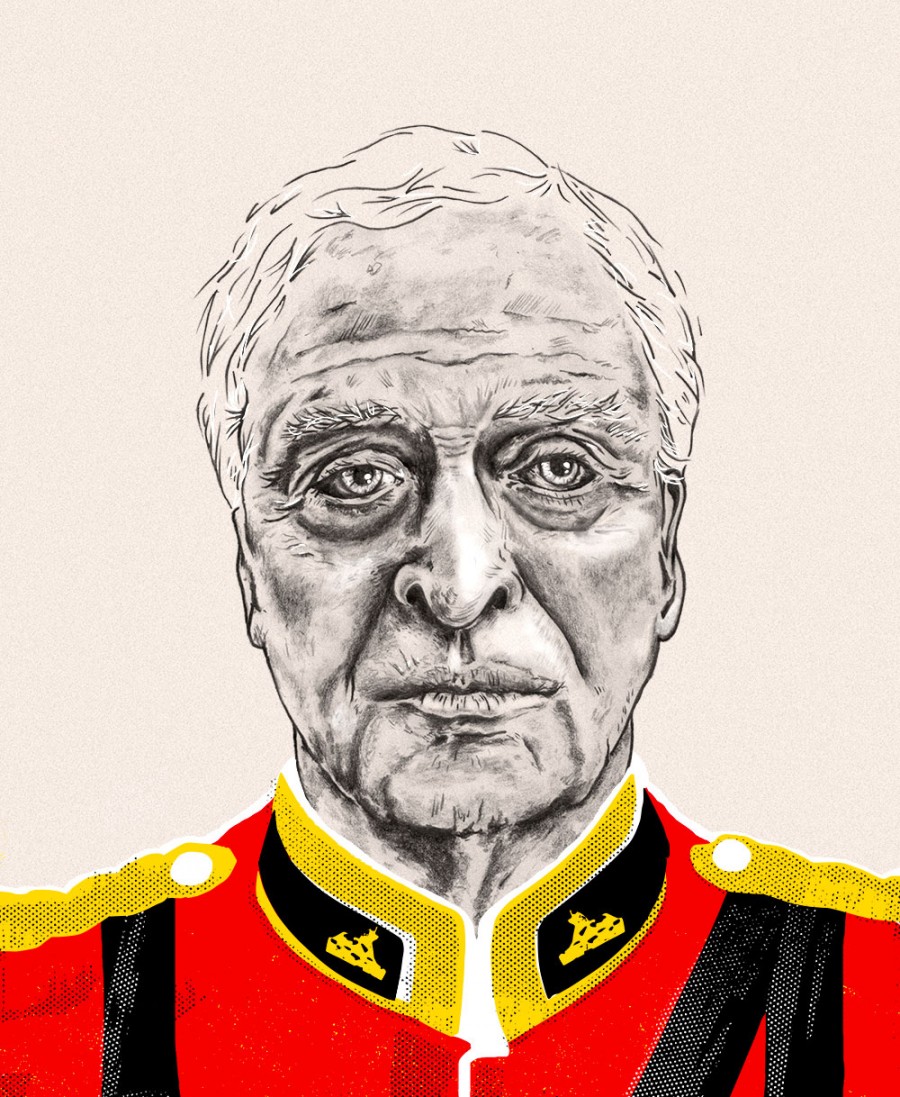

You character in Youth doesn’t seem to give a shit about what the Queen asks or demands. What are your feelings about being knighted?

I was very proud. I love the monarchy. I think they’re great and they’re a massive tourist attraction, too. If we didn’t have a monarchy I think we’d have about a quarter of the tourists.

But for you personally?

You get an Academy Award, it’s for a performance. You get a knighthood, it’s for a life.

Cary Grant once said: ‘To be familiar with audiences is the most important thing.’ And it’s been written that you followed that kind of advice.

Yeah well he was familiar. He was in the circus when he was seven or eight. I was very close friends with Cary Grant. I was doing a movie in Bristol, south of England, and I came out of my hotel suite one morning and there’s Cary Grant walking towards me. I didn’t know what to say because I was a big fan. I was like a young girl with Elvis Presley. I said, ‘You’re Cary Grant?’ He said, ‘I know.’ So I tried to think of a more sensible question. I said, ‘What are you doing here?’ He said, ‘My mother lives in the suite next door to you.’ His mother was sick. Instead of putting her in a hospital, he put her in a luxury suite in a hotel with nurses and everything. It wasn’t like a hospital. She could get everything in: food, order room service. We became friends after that.

Is there a film in your career that you would hold near and dear, like Fred does for his ‘Simple Songs’ in Youth?

I suppose the film I hold dearest is The Ipcress File. Because of the first time I ever went over the title.

Youth is released 29 January. Read more in LWLies 63, out now and available to buy from our online shop.

Published 22 Jan 2016

Take a look inside our latest print edition in which we meet British screen icon Michael Caine.

The Italian writer/director’s meditative and melodious drama hits UK cinemas on 29 January.

From Michael Caine conducting to a cartoon sausage, check out which releases are hot on our radar for the year ahead.