The cinema of Stanley Kubrick hinges on control, on characters vying for control over others, themselves, and their environment. It’s a constant quest for perfection and dominance, the manifestation of which ranges from the regimented routines of a prizefighter to the psychological supremacy of a marriage torn asunder. Above anything else, authority in wartime is the prevailing thematic obsession among the director’s 13-feature filmography.

Arriving four years after his low-budget combat debut, Fear and Desire, 1957’s Paths of Glory is a stirring tale of forlorn foxholes and callous bureaucracies, of blind ambitions and hapless destinies. Adapted from Humphrey Cobb’s novel of the same name, this World War One account concerns a group of French soldiers tried for cowardice after retreating or simply remaining stationary during fierce enemy fire.

Ensconced in elite chateau confines, surrounded by orderly, saluting underlings, a privileged discussion between generals George Broulard (Adolphe Menjou) and Paul Mireau (George Macready) revolves around a perilous portion of land, one currently occupied by the Germans and desired by the French. Mireau recognises the objective’s treacherous consequence, but a dangling promotion assuages any diffidence. Militaristic power straddles a fine line between acceptable authoritative rule and managerial extremism. The field of war is isolated, the obstacle is defined, and 8,000 pawns become part of an unscrupulous martial power play.

From the ornate, open spaces of the general’s estate, cleanly illuminated interiors with unobstructed aristocratic civility, Paths of Glory descends to the dank, squalid, death-tinged trenches, below ground and sinking in status. Mireau greets worn and weary soldiers with patriotic pleasantries, though his dismissal of “shell shock” as an unprofessional lack of self-control betrays his forbidding intentions. Engaged to enact the ill-fated mission, Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas) reluctantly accepts, for he is, alas, under orders.

Forged by the steel-jawed Douglas, Dax is poised, competent, and confident. Pushing past wavering uncertainty, his stoic charge through the gutter labyrinth takes on a subjective point of view, with fearful, determined faces staring back at the camera. While Mireau’s menacing influence yielded an aggressive progress charted by the dolly’s frontal retreat, Dax’s assured motion forward emphasises spirited advancement; his headlong march is unfazed and unflinching, leading by identification, not intimidation.

Valiant efforts only go so far, and Kubrick’s sweeping tracks sheathe the chaotic carnage in a meticulous illustration of frontline bedlam. As best-laid plans are aborted for sheer survival, obscured battle lines erupt in frenzied formal mayhem. Kubrick’s searing succession of devastating imagery scatters calculated explosions, synchronised character action, and purposefully fitful pans in mad dash desperation. Mireau revels in the sideline fight, but rages when despondent troops oppose the attack (only abusive safeguards prevent him from ordering artillery fire on his own men). It’s a failed attempt marred by intolerable insubordination – examples must be made. Dax evokes the officer most responsible, namely Mireau, who in turn sharply contends it is “not a question of officers.” Of course, Paths of Glory is very much a “question of officers” – it’s a question of agency and responsibility, of coveted sovereignty running counter to accountability.

A lawyer in civilian life, thus infused with a sense of judicial regulation and exactitude, Dax is the best defence for the accused. But his efforts are unproductive. Executions proceed, like everything else, with swift, professional certainty. The men search for solace, the dutifully sentenced and the instigating guilty alike. A priest proffers the consolation of higher power determinism, while alcohol provides mind-numbing relief; despite their exposure to superior exploitation, some still place their trust in a leader, believing Dax will come through. In the end, however, the condemned recognise their deficient sway. Selected by chance to die, they are convicted by fate. Threshold outbursts threaten composure, and last-minute demands (“Pull yourself together, act like a man!”) are but a final, cruel joke, indicating one last decision to be made, one they alone can actually make.

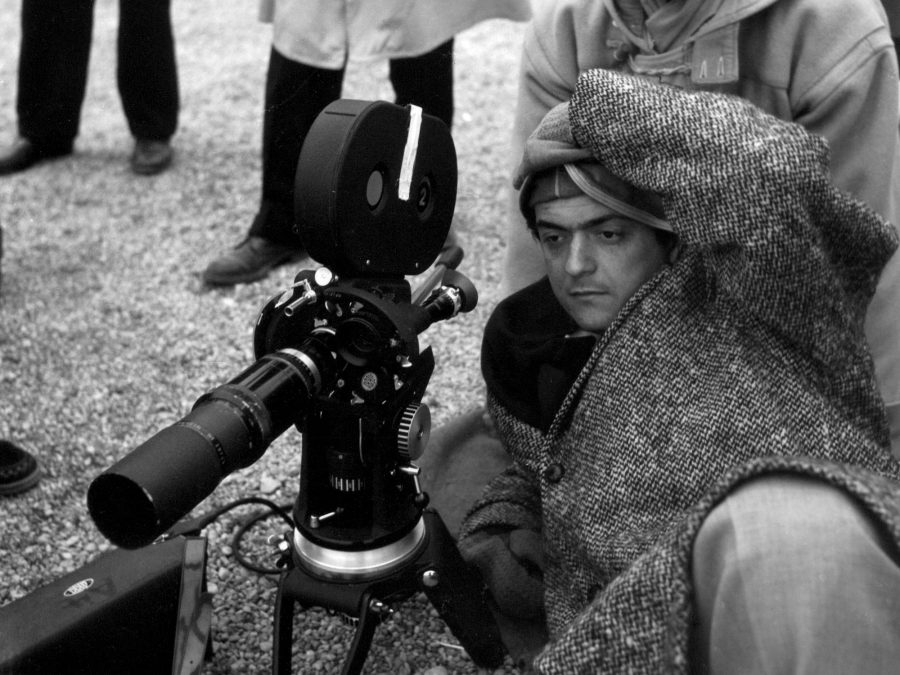

In war, coordination is key: mapping terrain, allocating enemy presence, tactically dispersing personnel. Soldiers are in formation with uniformity, discipline, and symmetrical care. Kubrick works the same way, employing a methodical manipulation of shot design, camera movement, and editorial intent, controlling viewer expectation and experience, guiding precise points of concentration. Just as alternating close-ups give respective individuals the upper hand and two-shots suggest a fleeting solidarity, moments of hostile battlefield bewilderment juxtapose with chessboard compositions of courtroom order and protocol. It is an extraordinary work, and perhaps the earliest example of a quintessential Stanley Kubrick film.

Published 20 Dec 2017

By David Hayles

Forty years after it left critics cold this majestic tragi-comedy stands as a testament to a true master of his craft.

As the acting icon celebrates his centenary, we reflect on one of his greatest performances.

Is Stanley Kubrick’s seminal 1968 sci-fi really the space opera to end all space operas?