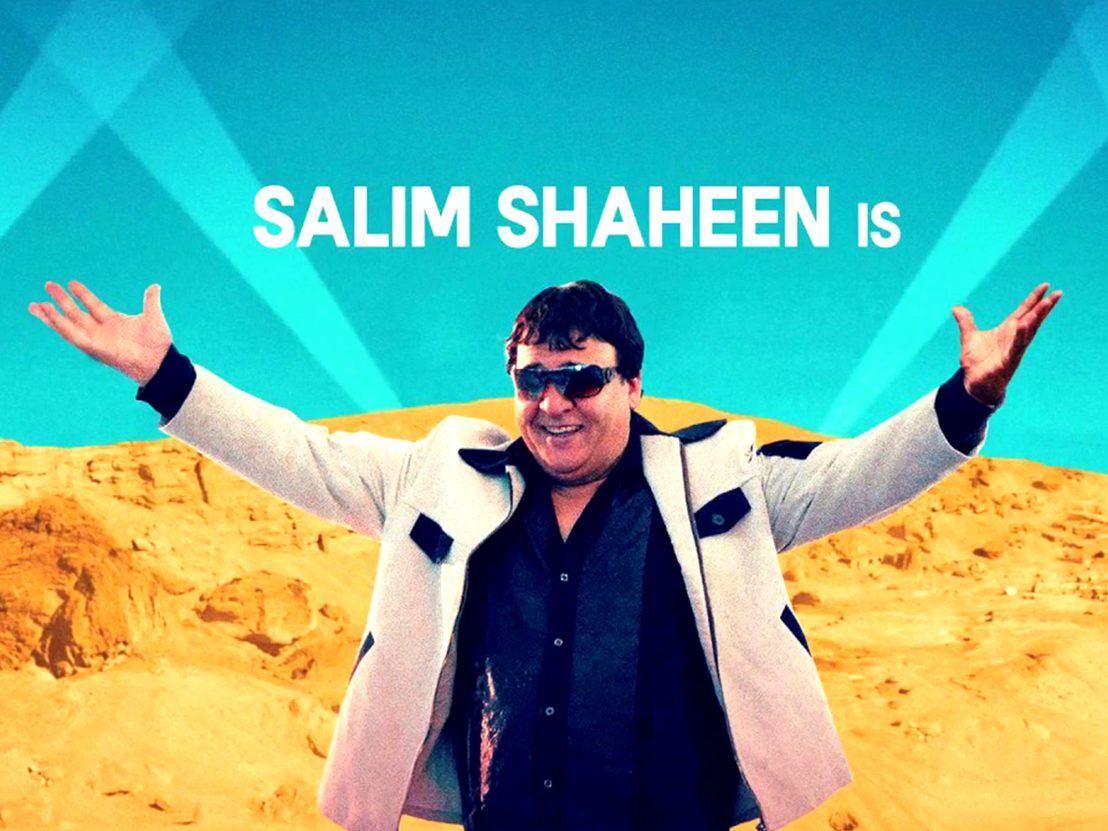

“You know who I am?” Salim Shaheen, perhaps the most famous entertainers in Afghanistan, asks an audience of soldiers. He’s here to screen his newest – and 109th – feature film, and his question is a playful wink to a country that knows him well thanks to his ubiquity on Afghan television. Shaheen is an actor, writer, director and all-around entertainer, the so-called ‘Prince of Nothingwood’ – a joke on Afghanistan’s zero-budget industry. His fascinating life and work are the subject of a new documentary by French journalist Sonia Kronlund, who was recently in Montreal to present the film at the RIDM (Montreal International Documentary Film Festival).

Kronlund is a French journalist best known for her popular radio show, Les Pieds sur terre, a cultural documentary series not unlike NPR’s This American Life that airs daily on France Culture. With straight-forward reporting, Kronlund allows subjects to speak for themselves, withholding commentary and opinion from her radio documentaries. She has covered a wide range of topics from linguistics to war, all with the same insatiable curiosity. Her reporting in Afghanistan is how she was first introduced to the larger than life Salim Shaheen and then years ago in Paris, a friend of hers gave her a collection of his DVDs.

“You know Salim’s DVDs are very funny, they are very kitsch, so I thought why not? I would take a chance and go meet him, it could be fun. Then when I first met him, and he started to tell me about his life and his childhood, it seemed to me that it was more than just fun, there is a much bigger story here,” she explained. In Nothingwood, Salim Shaheen’s newest film depicts the stories of his youth that first attracted Kronlund to the film. Not so much a coincidence, it reflects the blending of authorships of Kronlund’s film with Shaheen’s. Initially, Kronlund hoped to make a more traditional film about Salim Shaheen, blending observational documentary with reconstructions of Shaheen’s past. She quickly realized this was not going to be possible: Shaheen felt Nothingwood was as much his film as it was Kronlund’s. From the beginning, Shaheen tried to direct the reconstruction sequences and the large, expensive equipment proved inefficient for the conditions of making films in Afghanistan.

To get a better sense of Shaheen’s films, they are not tied down to the same conventions as we expect from mainstream cinema. They are made quickly, Kronlund says that Shaheen would rarely shot for more than thirty minutes per scene, and are a strange hybrid of Bollywood playback musicals and action extravaganzas. The real world violence of Afghanistan serves as a backdrop, using real weapons, chicken blood and soldiers in his films. Shaheen was even making films while he was a commander during the Afghan Civil War in 1992, having his soldiers work as actors and extras. As is clear throughout the film, shooting so quickly was not just a quirk of carelessness in technical qualities but rather a necessity. Kronlund would also have to make an adjustment, which is why she would work with Shaheem on “his” newest film about his youth, which would serve a similar purpose within Nothingwood. The pair would strike up a kind of partnership, sharing resources and to a certain extent, credit.

“Afghanistan teaches you to let go,” Kronlund says. “As someone who is a big control freak, I like to go to Afghanistan because I am forced to let go. It was no longer a question of what we are filming, who is the author, who is the one directing the scene or is anything that [Shaheen] saying true or not? It is all irrelevant.” Truth is rendered flexible and throughout the film and the experience of making it, there is a collective delusion in regards to truth.

In one scene, a father accepts money to have his daughter dance in one of Shaheen’s film, but even while she is literally dancing in front of him, he stands firm that she will not dance but not as a means of stopping her, but rather as a way of saving his reputation. “Do you know why he asks her to not dance?,” Kronlund says. “It’s to save face, it is to maintain his role as a father who is not selling out his daughter, even though that is what he is doing. It is a scene that explains layers of complexities, you have a girl who wants to dance, who is happy, who has a dream like an American teenage girl and a father who needs money but wants to maintain his honour, and who says she can’t dance. He knows she will dance, and he says you can’t be on camera, even though there are cameras everywhere.”

This scene comes to serves an important role in understanding both the culture of Afghanistan and its entertainment industry. Throughout the film, every man Kronlund meets says they would never allow their daughter to dance in public, one saying jokingly, “she prefers to die than to not be in Shaheen’s film.” Shaheen though may be pushing against culturally acceptable boundaries but is not really breaking any laws or regulations. Embroiled in conflict, chaos, and corruption – there are very few rules in what can be screened in Afghanistan – there is no standing government to enforce it anyway. “There are over 100 television channels in Afghanistan and the State Television doesn’t really work. The problem of censorship doesn’t really exist, and Shaheen will auto-censure himself enough, it is really a part of the culture,” she explains.

As the shoot winds down on Shaheen’s film, he brings Kronlund to the site of the Buddhas of Bamiyan, monumental statues of the Buddha carved into a cliff side between 507 CE (AD) and 554 CE. In 2001, the Taliban used to dynamite to destroy them. Shaheen describes his feelings about that event saying, “When the Taliban blew up the Buddhas, I felt they are against art, against culture and against all mankind. As an artist, that’s what I felt.”

Nothingwood premiered at the Cannes film festival in May 2017. Kronlund was joined by was by Salim Shaheen, Qurban Ali and another minor character from the film. The movie was received to a 20-minute standing ovation for an auditorium of 800 people. “I was there with my false modesty and the three Afghan’s, well,” and she raises her hands in the air with all the triumph of an athlete who has just captured the World-Cup. “We’re all a little cynical, I pretend to be modest,” Kronlund says, but there is a clear sincerity in Shaheen’s craft and presence that might be a little more honest. For Shaheen, Nothingwood is as much his film as it is Kronlund’s – in one interview when asked what it was like being the subject of a documentary he answered, “You know, I’ve made 110 films and this was one of the most difficult.”

While Shaheen returned home following the film’s Cannes success, his actor Qurban Ali did not. In Nothingwood Qurban is Shaheen’s actor of choice, a tall man with a generous smile who plays women. He is demonstrably effeminate, something that Kronlund believes is accepted because he has a wife and Afghanistan has a fairly high tolerance for eccentricity. Qurban, however, did not return home, claiming refugee status in France.

Since his return to Afghanistan, Shaheen has slowed down making films, but not necessarily by choice. “There was a period he was making a film a month,” Kronlund says. The economy has worsened significantly in the past few years though, and there is less money to make films and less money to buy DVDs. “Now, he’s making about a film a year.” In the extended aftermath of the American coalition that arrived in 2002, the country’s stability is constantly in question and at the moment, the Taliban still controls about half of Afghanistan. Daesh as well has become a presence, attacking mostly Shiite Muslims all over the country and violence continued to rise especially in Kabul. “One month ago,” Kronlund explains. “Shaheen was in a mosque where there was an attack where about one hundred people died. He was there, people died beside him. He is Shiite, and there are a lot of anti-Shiite attacks right now in Afghanistan from Isis.”

The Prince of Nothingwood is release 15 December. Read our review.

Published 23 Nov 2017

By Anton Bitel

Salim Shaheen, Afghanistan’s singular, strutting auteur, is the subject of this wonderfully entertaining doc.

By David Hayles

From Charles Bronson to Chuck Norris, David Hayles offers an indispensable guide to the cult production company.

By Sarah Jilani

Despite facing severe restrictions Iran’s most important filmmakers continue to give its people a voice.