It’s only in the last decade, since the release of his most widely-seen film, Regular Lovers that Philippe Garrel has re-entered the collective cinephile consciousness. It’s not that he’s ever been away – he’s been churning out entries in his profoundly auteurist canon of casual masterpieces every year or two since 1964 – more that he remains a mainstay of the festival circuit, even as the presence of his son, Louis, in his last five films has brought a more recognisable public face to such a singular oeuvre of cinematic introspection.

Although so few of his films are available on home video, en masse is the ideal means of working through Garrel’s back catalogue, especially given how intrinsically inter-connected and how nakedly autobiographical his work proves.

Jean-Luc Godard once described Garrel as being “as close as teeth are to lips to the idea of natural beauty,” in reference to his emergence as a wunderkind of the French New Wave with 1964’s Les enfants desaccordés, a formally playful short about a pair of young runaways on the lam that shared a kinship with his more celebrated contemporaries. The events of May ’68 were prefigured in his 1968 debut feature Marie for Memory and addressed directly in both 1969’s The Virgin’s Bed and the newly rediscovered 1968 short Actua I, but the disillusionment at their ultimate failure echoes all the way through to the literal reconstructions of Regular Lovers nearly four decades later.

That Garrel has never received the international attention afforded the likes of Godard and François Truffaut is unsurprising given the drug-addled strides into the avant-garde he made almost straight out of the gate. Early works such as Le Révélateur – a silent head-trip shot with the entire cast and crew tripping on acid – are a far cry from the reflexive variations of his later narrative features, those indebted to the influence of his friend and mentor, Jean Eustache.

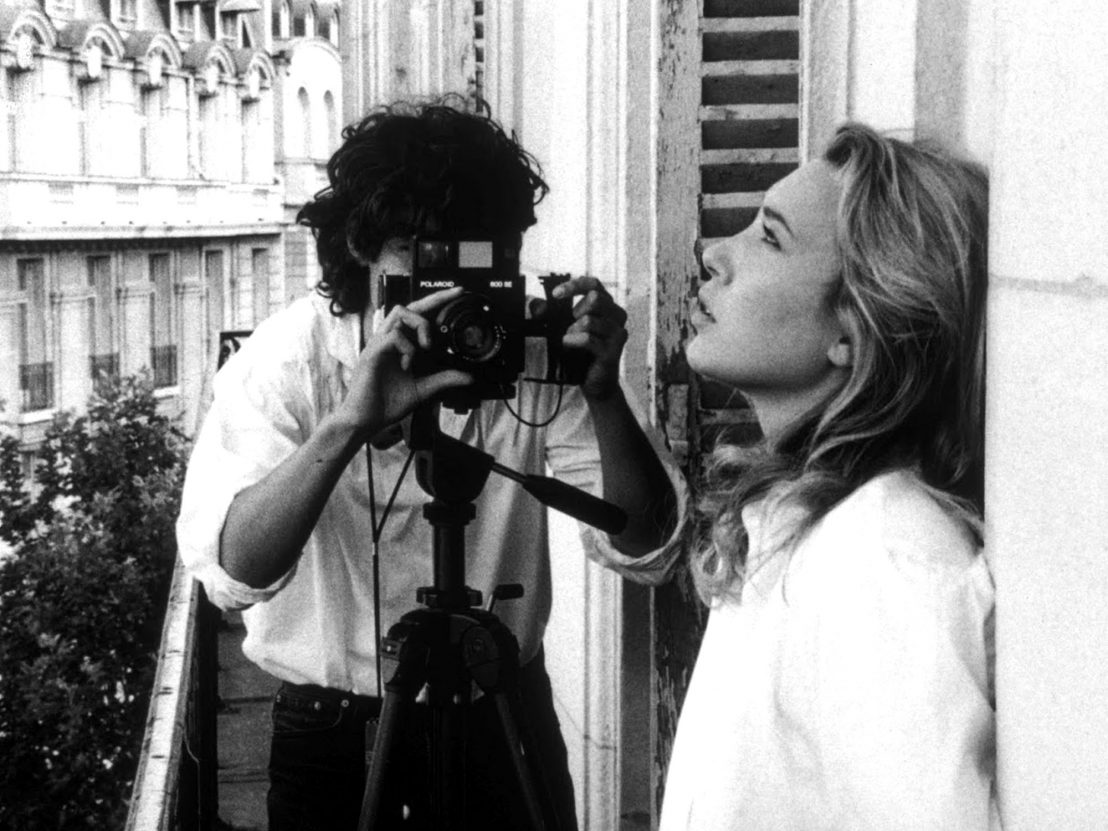

The division of Garrel’s work into two camps is unequivocally defined by his relationship through the first half of the 1970s with the German singer, Nico. As famous for her string of sexual conquests on the ’60s scene – from Iggy Pop to Bob Dylan – as her presence on the banana-covered Velvet Underground record and at Warhol’s Factory, theirs was a needle-fuelled romance of untold tempestuousness, the shadow of which hangs heavy over all of Garrel’s work through the ’80s and ’90s.

The couple made four films together, two of which have proved the greatest revelations of the retrospective, the key to unlocking the endlessly referential reverberations which would follow.

The mutual torment between the pair is already explicit in 1972’s The Inner Scar, a work of stark visual beauty and symbolic impenetrability. It’s a period piece – of sorts – a fantasy, even. Garrel and Nico play themselves, or versions thereof: wandering, fighting and collapsing through an arid emotional wasteland. He’s coldly silent, she a fountain of raw accusations; biblical and pagan imagery seared in vibrant colour as Nico wails on the soundtrack as though she’s swallowed a bassoon.

Yet you can feel a collaboration at work in The Inner Scar, ideas being worked through and presented, however esoteric they may appear at first glance. Jump forward three years and any such questions evaporate in an opiate haze. A nightmarish vision that rattles from the depths of heroin addiction, Le Berceau de Cristal is the pair’s most troubling work, and Garrel’s most ecstatically impressionistic film. It may also be his best – we’ll let you know as soon as the trembling stops.

Shot in their apartment in the dead of night, the film is undoubtedly Garrel’s love letter to Nico, her key-lit face and emerald eyes impossibly luminous. There’s little narrative to speak of, more an attempt to document the artistic process, as Nico sits or paces alone, writes and reads music and poetry, passes it to Garrel, gets high. Underscored by a startlingly intense psychedelic phantasmagoria, the use of colour astounds almost as much as the rippling textures of darkness unsettle. A single shot of Garrel, his face emerging from the blackness to stare directly into camera, eyes hollow and mouth agape is the most nightmarishly potent image in the director’s work – Eraserhead by way of Persona – a haunting retinal imprint like no other.

Garrel began his process of exorcising the doomed relationship as early as 1979 with the monumental L’enfant secret. While 1991’s J’entends plus la guitare explicitly addresses the affair in the most straightforward narrative terms, the ghost of Nico haunts the anxiety dreams of 1996’s The Phantom Heart as much as troubled lover Carole, coaxing Louis Garrel to his death in 2008’s Frontier of the Dawn or the meta-reconstructions of the wondrously titled She Spent So Many Hours Under the Sun Lamps, from 1985.

Film critic Kent Jones once wrote of Garrel’s films that “the action seems to be endlessly replaying as a crystallised eternal present within the chamber of memory,” and it’s never more true than when bulk-watching his work. His is a cinema of the incidental, few directors find such lucid beauty and grace in the spaces between action, dialogue and gesture, the beats seemingly outside of the ‘scene’. And yet there are countless episodes of transcendent power, as Jean Pierre Léaud says in 1993’s The Birth of Love, “all great art is based on nothing,” and Garrel pulls countless tiny miracles seemingly out of thin air.

The lack of judgement towards the characters in Garrel’s work is quickly taken for granted, but his fearless introspection knows no bounds. A conversation between wife, Brigitte Sy and himself in 1989’s great Les baisers de secours says it all:

“How can we discuss us or our lives as if they’re something interesting?”

“Because I’m not afraid to look at us.”

Published 6 Apr 2017

The 2015 Cannes Director’s Fortnight strand opens with a magnificent miniature from Philippe Garrel.

This early work from the French New Wave icon is a must-watch for cinephiles.

Fifty years on, this low-key drama stands as a glorious shrine to analogue film.