Released 40 years ago this month, Sidney Lumet’s pitch-black media satire Network anticipated the rise of Fox News, Mail Online, Donald Trump and the insidious convergence of reality TV and politics, as well as populist prophets like Russell Brand and Katie Hopkins. An acrid tragicomedy of operatic proportions, its apparent prescience has only grown in the time since its original release back in 1976. Lumet drew on his early TV experience to bring the parable of Howard Beale (Peter Finch) to life for the big screen. The film tells of a sacked newsreader who vows to kill himself live on air – “The first known instance of a man killed because he had lousy ratings.”

Exploiter-in-chief here is glassy producer Diana (a career-best Faye Dunaway). When she first hears of Beale’s plan to kill himself, her instinct is to make a show out of it. After successfully pitching ‘Suicide of the Week’ to the execs of the fictional United Broadcasting System, a nightly slot is devoted to Beale’s increasingly unhinged rants. Her amorality is cannibalistic (“I eat anything,” she hisses in one particularly memorable scene) and even sex is stewed with ambition: she gives herself an orgasm rattling off the network’s viewing figures and palms off a lover who tries to kiss her while she’s watching TV in bed. The juxtaposition of corporate double-speak with casual violence is grimly funny. One exec ponders, “Should we kill Howard Beale or not? I’d like to hear some more opinions on that.”

Voted among the top 10 scripts of all time by two American writers’ guilds, Paddy Chayefsky’s dialogue is at once potent, prescient and theatrical without ever feeling overly hysterical or stagy (Beale’s “why me?” visions, the farcical use of psychics on Wall St, a soothsayer who claims to know the next day’s news). Each character delivers some bleakly profound turns-of-phrase, such as when Beale rails against the “demented slaughterhouse of a world we live in.” Like Don Quixote or King Lear, his is a semi-persuasive middle-aged madness for whom death is a “perceptible thing with definable features” and whose ratings dip, depressingly, the more reasonably he behaves. He babbles to William Holden’s news president Max, an old friend, that he’s “imbued with some special spirit. It’s not a religious feeling at all; it’s a shocking eruption of great electrical energy. I feel vivid and flashing as though I’ve been plugged into some great electro-magnetic field.”

Max himself is fully aware of his own artificiality: in a row with his wife, he acknowledges, “here we are, going through the obligatory middle-of-Act-Two ‘scorned wife throws husband out’ scene.” Most satisfyingly for the viewer, Max resists Diana’s heartless tyranny. “This is not a script, Diana… Decaying love is the only thing between you and the shrieking nothingness you live the rest of the day…. You’re television incarnate, Diana. Indifferent to suffering; insensitive to joy. All is reduced to the common rubble of banality. Everything you touch dies with you, but not me.” By the end, television’s currents have corroded them all.

Since its release, Network has been hostage to its own eerily prophetic real-life reverberations, the saddest of which was Peter Finch’s death in January 1977 which denied him the opportunity to collect his Best Actor Oscar. But now its influence rages on in satires as varied as The Larry Sanders Show, The Player, The Truman Show, Magnolia, UnREAL and Black Mirror (especially Bing’s monetised rant in X Factor pastiche ’15 Million Merits’). Somehow, it managed to seemingly foreshadow almost every aspect of modern life: the sado-voyeuristic, vampiric drip-drip of increasingly invasive reality TV, the misplaced righteousness of producers, the ubiquity of advertising, the obsolescence of privacy, suicide videos, and the dangerous ascent of self-appointed social commentators like Alex Jones, a one-time fringe conspiracy theorist and “beat poet of paranoia” whom president-elect Trump has quoted in his speeches.

If you’ve never seen Network before, there’s never been a better time to watch it. It might be the best film-about-television ever made, its genius manifest in Beale’s famous “mad as hell” meltdown but also more subtly in the way it foresaw TV’s rabid potential, the unchecked voracity of those who have exploited it for their own personal gain. How apt that a counter-culture iconoclast like Sidney Lumet signalled the appropriation of the anti-establishment movement by another, even more potent iconoclast for just the greedy, destructive ends he warned us about.

Published 28 Nov 2016

Justine Smith examines how movies like The House of the Devil and Lords of Salem use nostalgia to expose a fractured national identity.

By Taylor Burns

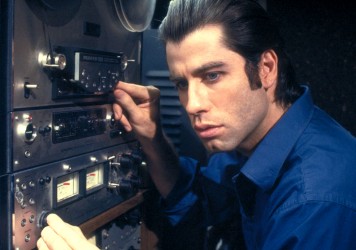

Brian De Palma’s taut Watergate-era thriller highlights the difference between what a country believes itself to be, and what it actually is.

In the first of a series of essays on Obama Era Cinema, Forrest Cardamenis counts the toll of US foreign policy during Barack Obama’s presidency.