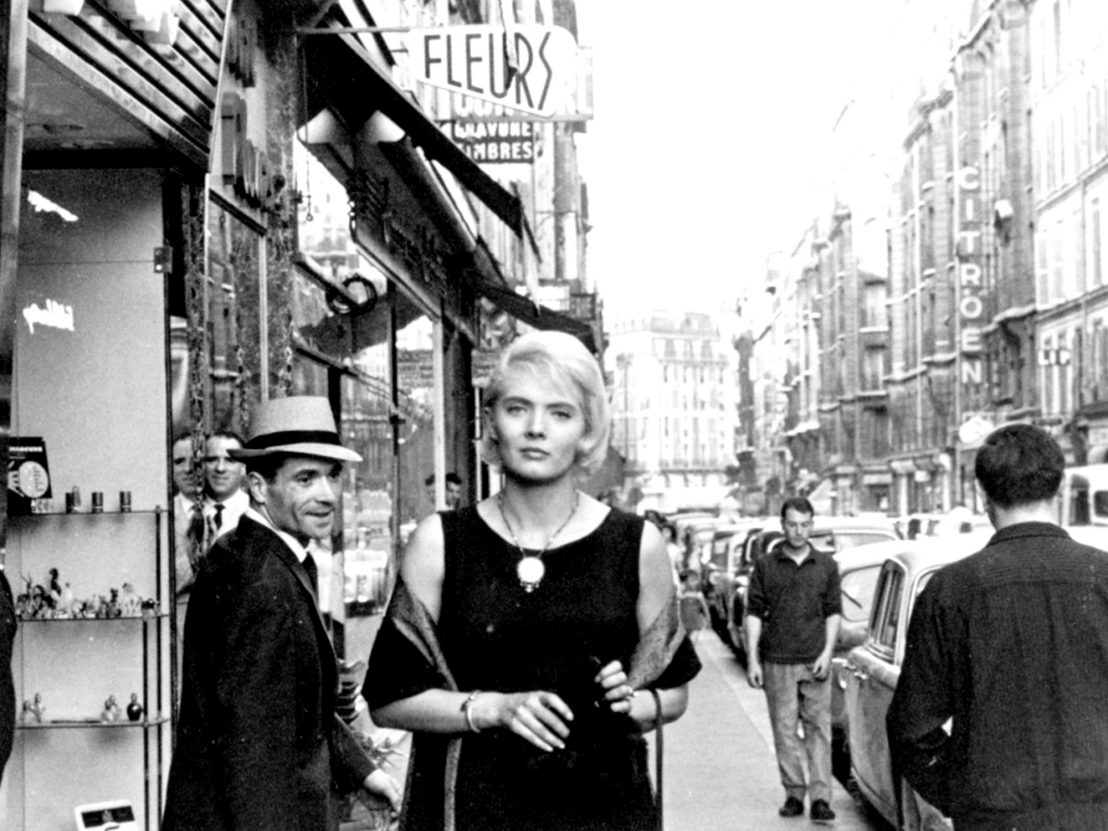

Agnès Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7 examines a woman walking, following the mournful titular protagonist around Paris in intimate detail. The film is not only an enjoyably unique exploration of coming to terms with illness and mortality but a snapshot of the French capital circa 1962, and even its cinematic culture.

Yet what really allows Varda’s second feature to stand out is how its perambulatory eye fills the screen with detail, so much detail in fact that an essay would be worthier to cover the sheer amount of interesting references to buildings, clothes, cars, objects, people, antiques and other paraphernalia that appears on screen. Though a similar emphasis was present in Varda’s previous film, La Pointe Courte, Cleo is almost solely constructed around such detail. Even the tiniest of things can relate to the character’s worries and concerns.

The film follows a famous singer, Cleo (Corinne Marchand), around the city on foot, by car and by bus. It is the day she is due her results back regarding tests she has had in search of cancer. Trying to earnestly avoid what this could mean for her, she wanders almost aimlessly from place to place; talking to strangers, meeting friends and getting taxis to nowhere. It is filled with superstition, its opening sequence of a tarot card reading removing, literally, the colour from the character’s life and everything she sees.

Cleo’s own mortality hangs heavily over her journey and the film explores Paris with this unusually dark emphasis. Ultimately, she finds out that fear itself is largely self-perpetuating but it was by traversing the most typical and everyday of scenarios that buffered the news of her final diagnosis. She is in search of headspace as much as physical space. But what did she see on her journey? Recounting it has as strange an effect as filming it had.

Cleo’s day unfolds like this: she leaves the fortune teller and walks down the street to a café where she meets her assistant (Dominique Davray). This assistant consoles her whilst she spills her coffee. She overhears a couple arguing before the pair leave and venture to a hat shop. “Everything suits me” Cleo insists and she buys an expensive winter hat in spite of it being summer. Time is potentially extended for her by the purchase. They take a taxi to Cleo’s flat and are harassed on the way by men. They laugh it off but Cleo darkness returns on seeing some unusual carved ornaments in a window.

Art students block the streets while the taxi radio tells of whiskey shampoo, the Algerian War, Kennedy and “Free the Bretons”. There’s a poster for Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou on a wall outside of the flat. Inside, Cleo has a variety of kittens, an extravagant bed, a piano and other furniture. Her lover (José Luis de Vilallonga) pops around briefly before a pair of musicians – one of whom is Michel Legrand – visit to show her some new material. A sad song makes her weep and she leaves in a black dress to wander again.

Cleo walks down the street and disturbs some pigeons. A man is performing, swallowing frogs. She flees in disgust as the eyes of men continually watch her. She heads to Le Dôme on Boulevard du Montparnasse and plays her last single on the jukebox. There are paintings on Le Dôme’s walls which she looks at whilst she drinks a cognac. The street beckons again. Another performer disgusts her with a needle poked into his arm. She finds solace in a sculptor’s studio where her friend (Dorothée Blanck) is modelling for a class. They leave together in a car and travel to the cinema of her friend’s partner to drop some reels off.

They watch a short film with cameos from Anna Karina, Jean-Luc Godard, Eddie Constantine, Jean-Claude Brialy and Sami Frey. The film is in fact by Varda, her short ode to silent comedy, Les fiancés du pont Mac Donald ou (Méfiez-vous des lunettes noires). The women leave and walk to Le Dôme again but there’s been an accident and they decide to take another taxi. Cleo gives her friend the new hat before she leaves and is dropped off in the park. She strikes up conversation with a soldier on leave (Antoine Bourseiller), distracting from her worries again. They catch a bus together to the hospital, so much detail in between, arriving to find she’ll need two months of treatment but should be fine. Her worry drove her frantic steps but she knows herself better now.

Why list these events? This maelstrom of information can only provide a glimpse at the endless detail in Varda’s masterpiece. Yet critiquing the film in a traditional way doesn’t quite work; its structure is too wandering, too drifting like a Situationist artwork. From recounting just the bare bones of what is seen on Cleo’s journey around Paris on that sad day, Varda’s endless and insatiable curiosity is perceivable and that is the real key. She understands that the ordinary has its own draws and wonders, even allowing for a cursed woman to briefly forget her upcoming ordeal with illness.

Such curiosity in the everyday – in things, thoughts and wanders – is really the mission statement of Varda’s filmmaking as a whole and it was Cleo who first walked it into being.

Published 30 May 2018

Read part one of our countdown celebrating the greatest female artists in the film industry.

Drahomíra Vihanová’s banned debut and several of her documentaries are screening for the first time.

Arthur Penn’s seminal crime thriller owes a lot to the likes of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut.