Carter Burwell has been responsible for carving the sonic architecture of some pretty notable films over the last 30 years. Despite regular collaborations with directors such as Spike Jonze, the American composer is most synonymous the Coen brothers, for whom he has scored nearly every film since their 1984 debut, Blood Simple. To celebrate the release of the Coens’ latest, Hail, Caesar!, Burwell talks us through some of the scores he has written for the brothers since his relationship with them began, almost by accident, back in 1983.

“I never planned to make a living as a musician, it was always an avocation, so I always had day jobs of one sort or another. I met Skip Lievsay – he did sound effects for films – and he asked me if I would be interested in doing some music for a film and it turned out it was the Coen brothers’ first film. I visited them in the editing room and they showed me a reel of the movie – they didn’t have a whole film yet. I don’t think they knew what they wanted, I don’t remember getting any sort of guidance.

“I went away and sent something back to Joel and Ethan. I didn’t hear anything from them for months, I think the investors probably wanted them to hire someone who actually knew something about film scoring, so they chatted to a lot of composers but eventually they called me. At that point I was in Manchester working on a record with a friend [Thick Pigeon] on Factory Records and they said, ‘When you’re ready let’s record Blood Simple.’

“We built a score based on the previous themes I had created. I did a lot of stuff on piano and I was experimenting with reel-to-reel tape a lot, too. So I came back to them with a mix of all the things that interested me at that time, in 1983. I wasn’t trying to imitate a film score at all, I was just doing stuff that I liked and thinking how it might relate to that film. None of us knew, technologically, how to synchronise music to film, so I would make and edit music timed to a stopwatch, knowing how long a certain scene was. Looking back, I really feel there’s a certain beauty to that naivety.”

“The strangest part was that Joel and Ethan came to me and said they wanted an orchestral score – they knew perfectly well that I had no experience writing orchestral music or any experience in classical music at all. So it was amazing – it still is amazing – to me that they wanted me to do it. Maybe it was out of loyalty, I don’t know. My wife thinks it’s because they don’t like meeting new people! So while they were shooting I was studying orchestral music, just trying to get some grounding in orchestration.

“I remember watching a rough edit and without any music to it the film is really cold and brutal. Gabriel Byrne is constantly getting beaten up and hit in the head, and you can’t always figure out why he’s doing what he’s doing. So I suggested trying to do something warmer with the music, to suggest that Gabriel Byrne’s character actually has some love for Albert Finney’s character and that any betrayal is motivated by love. They didn’t seem to like that idea. So I asked if they wanted something with a little more mystery, that was harder or colder and then they just said, ‘How about neutral?’

“As a composer you are usually one of the last people hired; Joel and Ethan had lived with the film for years at this point, so to have someone come in and say, ‘I’ve got a new idea that’s probably going to change the film in some fundamental way,’ … it’s hard as a filmmaker to be open to suggestions like that. That said, when I actually played them my idea they got it immediately, but I’ve now appreciated since then that it’s difficult for filmmakers to bring their film to a composer and keep an open mind about what they might do.”

“I remember when they just had a script, Joel saying he didn’t think this film was going to need a score. The way he saw it was that sound effects would basically play the role of a score. With it being set in a hotel, he already had some idea of the sorts of sounds that would be made if you opened the door, the creaking and croaking sounds of the building, this mosquito that’s in the film – he felt that all of these sounds might be all that the film needs.

“Barton Fink presents himself as this very successful playwright and a man of the world, fighting for the common man, but in actual fact he knows very little about the real world. That was my take on it, and I thought if I had this child-like piano, played high up, that would illustrate this innocent aspect of his character. Once I played it for Joel and Ethan they got the idea right away.

“With this film we included Skip [Lievsay] because we knew the role of sound design was going to figure so prominently. Skip also had to direct me to tell me where there was going to be a sound of the mosquito, for example, so I would match music to that. We divided the film up into its sonic spectrum of score and sound effects. It worked out really well, I think, but it’s rare that the composer and sound designer will sit down together and work.”

“Joel and Ethan didn’t know what the music should be but they did know what they didn’t want it to be, and that was comedic. There is comedy in the movie but they wanted to be sure that the violence was always believable. In the opening credits it is called ‘a true crime story’ and they wanted people to believe this was a real story.

“The goons in the film, Steve Buscemi and Peter Stormare’s characters, are the ones doing the killing but they’re also idiots, they’re buffoons. So that was a challenge and in the end I decided the best approach was for the music to not only take the crime aspect seriously but take it too seriously – so seriously that it’s almost ridiculous. I studied a lot of film noir scores and for the goon characters I was already somewhat familiar with Scandinavian folk music; all the characters have Scandinavian names and the landscape itself is covered in snow, so I thought maybe some Scandinavian instruments – there’s a really good instrument called a hardanger fiddle – would work.

“I found this folk tune called ‘Lost Sheep’, played on fiddle, and I ended up developing that into the main theme. It’s a hybrid of a Scandinavian folk tune and film noir instrumentation. When they were first putting the TV series together somebody reached out but my schedule wouldn’t allow me to work on it so I said I wasn’t really interested, but if they wanted to use any music from the film that was fine by me. I saw the pilot and because the music was kind of like the music I wrote for the movie, but at the same time different, I found it a bit unsettling.”

“In Joel and Ethan’s films that feature of lot of songs, they are usually referenced in the script. The actual songs might change if they can’t get them or whatever, but they felt that the music Jeff Lebowski listens to is very illustrative of his character. So it was very important to have Credence Clearwater Revival songs and Bob Dylan tunes. Those songs were written into the script, so I knew there was going to be a lot of them and that my work was going to be tying things together.

“Anything I wrote, I also wanted it to sound like a song so you were never aware of a film score. It’s hard to say why but I guess with a film score you have a piece of music that is coming through the speakers, but it’s not coming from anywhere, nobody has turned on the radio or is playing an instrument. With The Big Lebowski I didn’t want to have a film score well up from the speakers – everything I wrote for the film has a source for it. For Jon Polito’s character, who is a private detective, I wrote a score for music to be coming out of his car radio, and there was a German techno-pop band who I wrote music for. Everything was designed to be presented as a song.”

“This was an interesting one. From the moment they hired me – before they had shot the film – Ethan was dubious that music could work in the picture at all and Joel felt there was a very dramatic need for music in the film. So we were all a bit unsure about what the music would be or if there even would be music. So when I started work on it, every time a musical instrument entered this world, it seemed to reduce the level of tension in the film – and this film is all about tension.

“I tried all these different sounds, even one that didn’t sound like instruments, but it would deflate the balloon a little. I was never able to find a musical instrument that didn’t make things worse, so in the end my solution was to use sounds that don’t have a beginning or end, things like a Tibetan singing bowl.

’There’s a scene where Javier Bardem’s character is threatening a cashier in a gas station – I tuned into the same frequency of the electrical hum of that room, to intensify the sense of threat as the scene goes on. You never notice there’s any music because it’s snuck in. The only place in the entire film where there is anything you would recognise as music is a piece I did for the end credits. I think the music in this film was about playing the landscape; there’s something about the landscape that has resulted in a lot of violence and cruelty in this part of the country.”

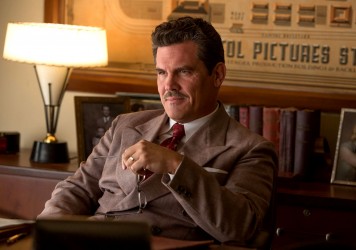

“There are a lot of films within this film: there’s a Roman epic, a western, a melodrama, a tap dance number, all these different films that are being made that you see little bits of. I knew I had to write music for all these films, but they aren’t finished films so realistically there wouldn’t be music written for them yet.

“Scoring all these different films involved a lot of research. I looked at scores for Ben-Hur and Quo Vadis, which Miklós Rózsa had composed – he’s known as the father of film noir music but he also did these grand Roman spectacles too, so it was really interesting to study his work. He was making up his own idea of what music sounded like two thousand years ago, inventing what music around the time of Christ would have sounded like.

“The biggest challenge was tying it all together to make sure it sounds like you’re watching one film. My approach was to have some recurring melody that appears in different guises in the different films, to create a thread that would run through the film even though this melody would be played in many different ways across the different sub-plots of the film.”

Hail, Caesar! is in cinemas 4 March.

Published 23 Feb 2016

Jerry Lewis’ classic 1961 comedy provided inspiration for the Coen brothers’ peek inside the Hollywood machine.

The Coen brothers return in scintillating and provocative form with this complex satire of 1950s Hollywood.

Two men, operating as a single creative body. Little White Lies was offered a rare audience with the Coen brothers.