Potsy Ponciroli’s defiantly old school oater is a modest treat with a barnstorming turn from Tim Blake Nelson.

Old Henry is a western directed by Potsy Ponciroli that places us in 1906 Oklahoma County where Henry McCarty (Tim Blake Nelson), a widowed farmer, is living with his teenage son Wyatt (Gavin Lewis) among the temperate grasslands. While their existence within this far-flung rural idyll seems colourless, their life together is pleasant and uneventful enough.

That is until Henry finds a wounded sheriff (Scott Haze) and takes him in, drawing the attention of a menacing outlaw (Stephen Dorff) and his henchmen who hound Henry’s house to apprehend their target and recoup the money he stole from them.

As sharp and slender as his pickaxe, Nelson’s Henry fits right into this oddly tempered setting, with a droopy handlebar ’tache dragging down the corners of his mouth. Little surprise, considering his filmography of western and action roles, most recently the Coen brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.

Though Henry acts like a “mild old sodbuster” he conceals an inner secret: one it would be churlish to spoil, but it involves a long-hidden secret rising to the fore. He’s an intriguing character, but as his poorly-sketched son Wyatt, Lewis is a little overwrought, his accent wobbly and perma-frown grating.

Old Henry aptly describes itself as a ‘micro-western’, and stakes are indeed rather low. Mainly taking place in and around a single house, it’s easy to be charmed by the story’s leanness and economy. When things give way to action, it becomes something of a western video game, with characters sniping at one another around this domestic battleground. This never feels cramped or dull, yet the rich mythology of the genre that eventually becomes relevant as the plot progresses doesn’t quite seem to be able to square up with the interiority of the setting.

Though verging on silly at times – Dorff uses the words “reconnoiter” and “skedaddle” in the same sentence – the film is certainly bags of fun when the action kicks off. One kill is so satisfying that the audience in Venice actually hooted and cheered in delight as Nelson twirled his gun in a self-aware flourish. Jordan Lehning’s brooding, cello-heavy score is deployed shrewdly, and the nimble staging and editing result in satisfying scenes that don’t betray the limits of the shooting location.

Western textures of horsehair, denim and suede always translate nicely to the big screen, but here they don’t quite seem like they have been captured to the best of their potential. Compared to something like Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog, there’s really no competition as to which offers up a more immersive, sensory frontier experience. The western trademarks are here, but not quite part of the film’s soul; we have a hero and a villain with a burr in his saddle, but no meaty or satisfying interrogation of landscape, masculinity or borders to really give us something to chew on.

Old Henry presents a simple premise, and the notion of an isolated family protecting themselves from the virus of modernity is rather pertinent. Unlike its protagonist, however, it’s a film which does not appear to hold hidden depths. Western aficionados may enjoy the film’s uncomplicated approach and satisfying shootouts, but beyond that, it’s unlikely to stand out within the genre’s rich canon.

Published 7 Sep 2021

Ana Lily Amirpour returns with a blissed-out, techno-powered riff on the time-honoured superhero movie.

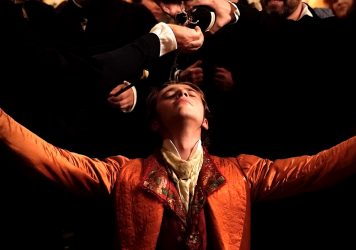

Xavier Giannoli’s pristine adaptation of Balzac’s ‘Illusions Perdues’ is a raunchy romp through post-Revolution France.

By Steph Green

Harry Wootliff’s follow up to 2018’s Only You focuses on a relationship so toxic it’s almost radioactive.