For many younger cinephiles, the films of Werner Herzog provide an ethereal gateway drug to the world of hardcore European art cinema. I say this not to denigrate the quality or intellectual depth of the work, but as a fond personal recollection of seeing Aguirre, Wrath of God way too young and feeling worried for the actors on screen in a way that was both exciting, terrifying and above all, exciting. The images in this film didn’t look like the images in other films.

Herzog is someone whose estimable screen catalogue provides both extreme diversity and satisfying unity at the same time – that is to say, for Herzog, no subject matter, genre or style is off the table, as long as it subtly ascribes to his unique view of the world and humanity. The filmmaker has spoken at length about the meaning and rationale for his work, and on occasion has stated that he is not a filmmaker, but a writer, and that the images are processed entirely from his thoughts and ideas.

Personally speaking, the pleasure that I have accrued from his films relates to his ability to locate poetic order amid the chaos and mystery of the world, its landscapes and its people. He is someone who proves that you can be a humanist while also believing that life is little more than a meaningless nightmare of suffering. And so, ahead of a BFI retrospective of his work, here are my top ten Herzog essentials.

10. My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? (2009)

At the 2009 Venice Film Festival, the majority of Herzog-based energy was trained at the world premiere of his novel, Nic Cage-starring crooked cop thriller, Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans. Yet, another, superior Herzog joint rolled out in a surprise slot, and it’s a film which definitely gives an affirmative answer to the question: is Michael Shannon the new Klaus Kinski? The film is Herzog’s take on the “true crime” sub-genre, but of course bites its thumb at convention, with Shannon playing a frazzled actor who becomes so fixated on his role that he attempts to murder his mother with a sabre. Contains an amazing scene of Shannon and Brad Dourif tooling around at an ostrich farm.

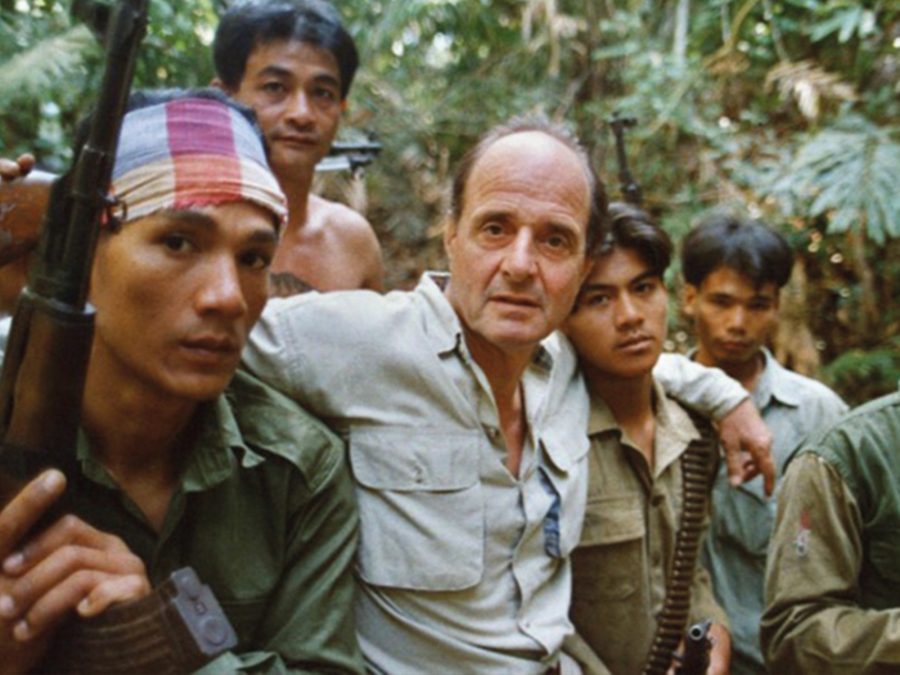

9. Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1997) / Rescue Dawn (2007)

While he’s not one for sequels, Herzog is known for revisiting and recalibrating his past works, and the story of German aviator Dieter Dengler provides the material for multiple films and books. Little Dieter Needs to Fly is a documentary about Dengler’s unlikely escape from a Laotian POW camp during the Vietnam war, with Dengler himself on hand to talk through the details. Rescue Dawn, meanwhile, offers a straight fictional retelling with Christian Bale in the lead. It sounds like a standard triumph-over-adversity newspaper cutting, but Herzog focuses instead on the human body’s capacity for suffering and the human spirit’s capacity believing in impossible things that may just save our lives.

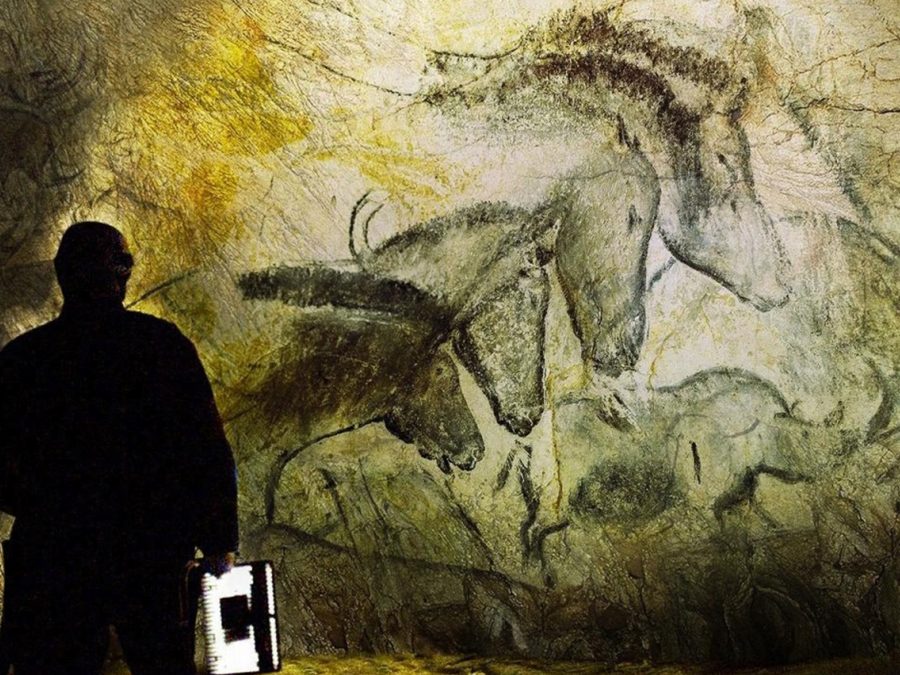

8. Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010)

It wasn’t going to be long before Herzog dipped his toe into the translucent pool of 3D technology, and he came up trumps with 2010’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams. He heads on an expedition underground to the Chauvet Cave in Southern France to train his camera (and special lenses) on the primitive paintings that were created many tens of thousands of years ago. The transcendent spectacle of seeing the paintings and the hidden natural enclosure would likely be enough for some viewers, but as with all of Herzog’s documentary work, it’s his spry, inquiring narration that tips this over the top.

7. Grizzly Man (2005)

Where Herzog famously espouses a view of the world as being dominated by chaos and confusion, the subject of 2005’s Grizzly Man, amateur environmentalist Timothy Treadwell, lived by a very different set of beliefs that ultimately led to him being killed by a hungry bear in the wilds of Alaska. The film is almost like Herzog saying to the viewer, “See? See what happens when you embrace the idea of harmony and grace? You will die horribly.” It also contains one of the greatest, Mondo-esque scenes in the director’s canon, where Herzog is filmed listening to an audio recording of Treadwell’s death and advises the owner of the tape to never listen to it and to destroy it (advice he later reneged on saying it was the product of his own shock).

6. Fitzcarraldo (1982)

Without meaning to sound facetious, 1982’s Fitzcarraldo exemplifies the can-do spirit of the Herzog project. The art of filmmaking is one that is bound to practical logistics and the understanding of technical processes, and the famous sequence of Klaus Kinski organising the transport of a steamboat over a hill deep in the Amazon Rainforest is one of the great metaphors for the toils of making movies. The film offers jaw-dropping spectacle by the bucketload, and you know you’re seeing images that were created without any conventional safety nets. Yet as the years have passed, there’s a faint whiff of colonial celebration to the story of a man attempting to introduce opera to depths of rural Brazil.

5. Fata Morgana (1971) / Lessons of Darkness (1992)

Yes, we’re cheating a little by doubling up this pair of “ambient” documentaries, but there’s so much visual and thematic connectivity between the two that we thought we’d do a double-bubble. In fact, “documentary” doesn’t feel like the right term for Fata Morgana and Lessons of Darkness, which offer stark images of landscapes from around the globe and use camera position, editing and music to subvert and, in many cases, heighten the meaning. The slowed-down sequences of billowing flame clouds in a post-Gulf War Kuwait give the sense of a fantastical apocalypse in motion.

4. Stroszek (1977)

A personal, slightly left-field favourite among Herzog’s early missives, 1977’s Stroszek is a comic tirade against American cultural imperialism and is famous for being the film that Joy Division’s Ian Curtis was watching before he took his own life. The film marks the second and final collaboration with the mysterious actor and musician Bruno S. who exudes such unorthodox screen presence that you don’t need to worry too much about following the mayhem of the plot about a German alcoholic seeking (and very much not finding) his fortune on the barren flats of Wisconsin, USA.

3. Nosferatu (1979)

We have to remember when we watch Robert Eggers’ forthcoming remake of Nosferatu that Werner Herzog already made an excellent one back in 1979. If there’s one thing that Herzog is very much not known for it’s sex and eroticism, so this one is very much an outlier on those terms, as it’s a film which is lifted no end by the chemistry between Klaus Kinski’s Count Dracula and Isabelle Adjani as Lucy Harker. It’s a film that’s rich with visual metaphor, and uses its central tale to speak of a world that’s crumbling from within. It’s also not a horror film, but rather a lilting study of a man driven by impulses he has no way to suppress.

2. Aguirre, Wrath of God (1972)

If we’re formulating lists of films that we’d like to see projected on an IMAX screen, then Herzog’s seminal, shocking 1972 historical epic of colonial adventure in the Amazon would be very near the top of the pile. From its opening shot of conquistadores filing carefully along a precarious mountain ridge, set to the ambient strains of German prog band Popol Vuh, to its agonising finale with star Klaus Kinski set adrift on a raft with only monkeys for passengers, it’s still an awe-striking work of imagination and ingenuity that looks and feels like nothing else before or since. Its strident and articulate political critique of imperialist plunder still rings as loudly as it ever has.

1. The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974)

One thing to say about Werner Herzog is that he’s made an extraordinary amount of films, and he has tended to make at least one or two great ones for the last five decades and counting. Our top four here draw very much from a vintage run in the 1970s, and this is perhaps a reflection of the freedom he was given to tell such tales at a time when funding was neither so restrictive nor so hard to come by. 1974’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser is one of his most moving, philosophically rich and least didactic works, as it tells of a nineteenth-century foundling (played by Bruno S.) who spent the first 17 years of his life chained up in a dark cellar with only a toy horse for company. The film charts his subsequent acceptance into and rejection from bourgeois society, and where Herzog has often focused on the chaos inherent in nature, this is a film about society as a phantom of structure and logic. In the end, chaos is everywhere, certainty is a myth, and the world – for better and for worse – will remain a location of infinite mystery when your time on it finishes up. Watching it again now for its 50th anniversary year, you get a sense that it’s one that has influenced many modern filmmakers, from Greta Gerwig (Barbie) to Yorgos Lanthimos (Poor Things).

Published 6 Jan 2024

A personal diary from a filmmaking workshop in Peru, hosted by the legendary German director.

By Tim Cooke

Encounters at the End of the World features one of the great existential moments in modern cinema.

Two writers make their case for the most eccentric moment in the director’s career.