By the time Monsters Club came out, writer/director Toshiaki Toyoda and the actor Eita had history. After all, Eita made his big-screen debut in Toyoda’s Blue Spring, and then had also starred in his 9 Souls and Hanging Garden.

So by 2011, the two were regular collaborators, even if Toyoda’s rapid rise as a filmmaker in the early 2000s was cut short in 2005, just before the release of Hanging Garden, by his arrest for drug possession and the ensuing media scandal which would see him blacklisted. Toyoda made a comeback in 2009 with the pointedly titled The Blood of Rebirth, which he followed up with Monsters Club. But before starting on those films, he retreated to a cabin in the wilderness.

A similarly remote, snowbound cabin is also the principal location in Monsters Club, making it hard to resist reading the film as at least in part Toyoda’s attempt to work through issues about his own criminality and the shortcomings of a society from which he had exiled himself. More obviously, though, the film’s misanthropic protagonist Ryoichi Kakiuchi (Eita, contained yet intense) is modelled on the real-life Ted Kaczynski, aka the Unabomber, who from his isolated Montana cabin began waging a national bombing campaign, and after leaving three people dead and 23 others injured, was finally arrested in 1995 on a tip-off from a sibling.

Like Kaczynski, Ryoichi is living self-sufficiently off grid, is hand-crafting explosive devices in his cabin with which he targets CEOs and academics perceived as facilitators of industrialisation and capitalism, and is writing a manifesto (extracted in voiceover at the film’s beginning) in which he justifies his terrorist actions. And where Kaczynski inscribed the initials ‘FC’, standing for ‘Freedom Club’, in many of his bombs, Ryuichi carves ‘MC’, for ‘Monsters Club’, into his DIY devices.

Ever since featuring so prominently in Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead, the cabin in the woods has also become an archetypal, iconic locus for horror. Sure enough, even as Ryoichi regards his targeted victims as belonging to a ‘monsters club’ of elite power brokers, he finds himself, in the family cabin, forming a club of his own with his nearest kin, both living and dead, who haunt the place like a tormented conscience.

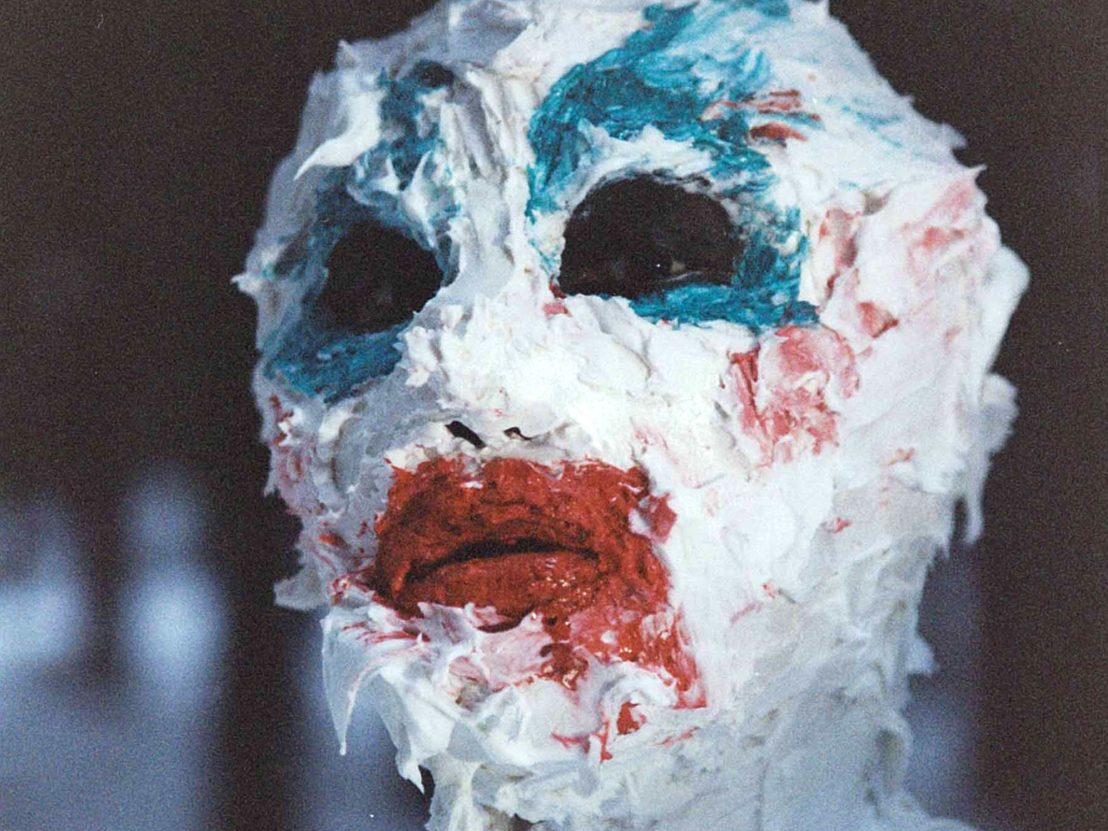

His first visitor is a monster – a silent, menacing clown creature in grotesquely thick white shaving cream, with smeared splashes of bright red and blue over its mouth and eyes. Soon there will be more visitors: his brothers Kenta (Ken Ken) and Yuki (Yôsuke Kubozuka), and his sister Mikana (Mayû Kusakari). Yet only Mikana is actually alive, while the others are taunting, sneering ghosts, their presence accompanied by electronic glitches in the soundtrack. Conjured by cabin fever, these monsters of the mind keep goading Ryoichi to stop his murderous campaign and to join the rest of the family on the other side.

“Over 33,000 people each year choose to take their own lives,” Ryoichi says near the beginning of the film. It’s a trend that he hopes to buck with his current wilderness existence, away from the rat race that he believes destroys people’s souls. But suicide is part of his family history, and is obviously plaguing his thoughts.

To avoid this fate, he has severed his links to society, and lives off what he, himself and alone, hunts and reaps and forages from the land. Yet in his isolation in the middle of nowhere, Ryoichi strikes an incongruous figure, off kilter and out of balance. In the lamplight, he smokes cigars, reads and listens to arias on the gramophone while dressed all in a buttoned-up white shirt and dinner jacket – clothes which he also wears while stalking and killing animals in the mountainous forest. Ryoichi may act as if he has gone wild, but he is dressed for civilisation. That contradiction drives Toyoda’s film, as we are invited to see if there is a difference between man and monster.

Monsters Club is a portrait of an unhinged individual living in grief and in extremis, painted in the colours of politics, psychology and poetry. Elegantly shot and scored, almost preternaturally calm at its surface, yet full of repressed agony and anguish which every so often Ryoichi disinters like one of his cabbages buried beneath the snow, this is the story of a disaffected, delusional, despairing man, dressed as a clown and intent on violence against himself or others, made eight years before Todd Phillips’ Joker would pursue similar themes in a very different way.

Monsters Club is available as part of Toshiaki Toyoda: 2005-2021, a limited edition Blu-ray digipack of six films by the director, released on 18 October via Third Window Films.

Published 18 Oct 2021