On 19 February, 1910, Florence Lawrence opened the newspaper and discovered she was dead. The actress recalled seeing her obituary on her way to work, writing in a 1914 article for Photoplay, “I… was startled to see several likenesses of myself staring me in the face, topped by a flamboyant headline announcing my tragic end beneath the wheels of a speeding motor car.”

The story was obviously a lie, but it made Lawrence’s career. The ensuing publicity frenzy made the silent-era star a household name, at a time when most film actors didn’t receive credits for their on-screen work. They were simply nameless faces to their fans, which is why Lawrence is often called the “first movie star” – and it was all thanks to a manufactured crisis.

Prior to her death and resurrection, Lawrence had already starred in over a hundred short films. Following in the footsteps of her stage actress mother, Lotta Lawrence, she had put in stints on the vaudeville circuit and at early American studios like the Vitagraph Company, before landing at Biograph, the launching pad for future industry heavyweights DW Griffith and Mary Pickford.

According to Lawrence’s biographer Kelly R Brown, the actress had appeared in most of the shorts Griffith directed for the Biograph Company in 1908, and built a brand on the studio’s ‘Mr and Mrs Jones’ comedy series. She was so popular that fans called her “the Biograph girl,” in absence of an actual name – Biograph, like all other studios of the early 20th century, did not disclose the names of its actors.

Lawrence knew she was worth something to Biograph, and asked the studio to increase her pay repeatedly. Her bosses fired her instead, but she was soon snapped up by Carl Laemmle at IMP, shorthand for the Independent Moving Pictures Company. Although IMP was a much scrappier outfit than Biograph or Vitagraph, Laemmle had grand plans for his new star. He intended to capitalise on her popularity with a strategic media blitz, all building to an outrageous finale.

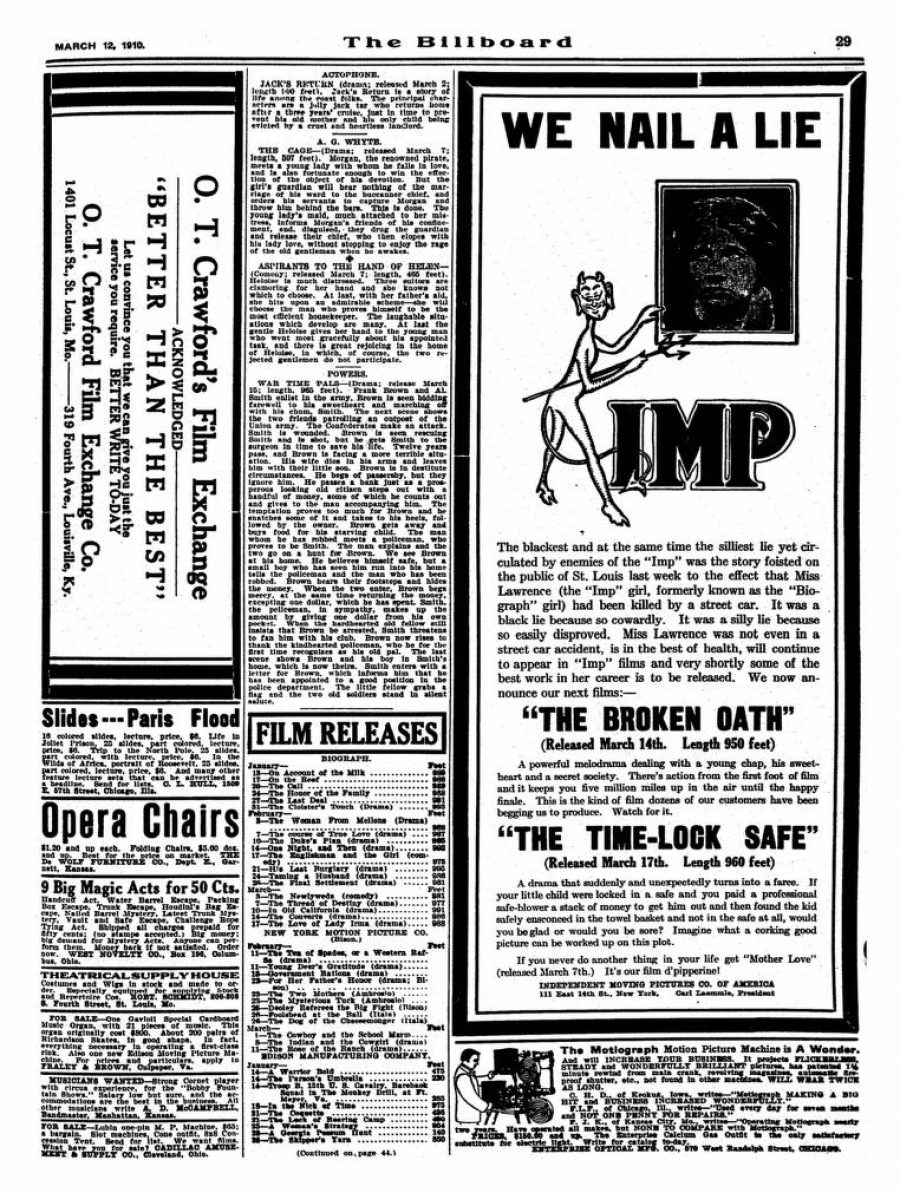

The first promotion ran in Motion Picture World in December 1909. It hyped the holiday film Lest We Forget with a small portrait of Lawrence. The text next to her photo announced her new studio allegiance: “She’s an Imp!” Two months later, the death rumours started, though their origins are somewhat murky. Lawrence supposedly saw the report in a New York paper, but many accounts cite St Louis as the source – and in that version, she was run over by a streetcar. In any case, Laemmle responded with a now famous “correction” that ran in trade papers with the headline ‘We Nail a Lie’. This ad included another photo of Lawrence, along with text insisting the actress was alive and well, and about to star in the new IMP features The Broken Oath and Time-Lock Safe.

Despite Laemmle’s supposed outrage over this lie, historians credit him with starting the rumour himself. His correction, which mostly functioned as advertisement, reeked of opportunism, and so did the stunt he pulled next. To further dispel the death rumours, IMP sent Lawrence out to St. Louis with another studio player, King Baggott, for public appearances. They hosted receptions and delivered short speeches at various venues across the city, but the true strength of Lawrence’s newfound star power was manifested at Union Station. There, according to a Laemmle biographer John Drinkwater, fans “demonstrated their affection by tearing the buttons from her coat, the trimmings from her hat, and the hat from her head.”

Lawrence was officially a celebrity, with the money to match. At IMP, she was pulling a reported $1,000 a week. She would stay at the studio for less than a year, however, bouncing to Lubin Manufacturing Company for another short stint before starting her own production studio, the Victor Company, with her husband Harry Solter in 1912. She would also run a cosmetics store and invent a precursor to the car turn signal, when she wasn’t making movies.

But the death hoax publicity bump was short-lived. Lawrence’s fame began to wane in the mid-1910s, at which point she split from Solter and their production company was absorbed by Laemmle’s latest venture, Universal Pictures. She struggled to find consistent work in the 1920s and 1930s, landing a few bit parts at MGM. In late December 1938, the 52-year-old was found dead in her apartment with a note addressed to her roommates: “I am tired. Hope this works. Good-by, my darlings. They can’t cure me so let it go at that.” Lawrence was laid to rest in the Hollywood Forever Cemetery, where her headstone reads ‘The First Movie Star’.

Published 14 Apr 2019

How a Kansas-born chorus girl turned silent era icon walked away from Hollywood and became an even bigger star.

In 1978, the comedy icon’s body disappeared – was it a ransom plot or a practical joke gone awry?

By Emma Fraser

For a brief period during the 1930s, this unlikely idol became part of Hollywood’s glamorous elite.