“You bloody maniac, what do you think you’re doing!”, yells a woman (Katya Wyeth) at Peter (Shane Briant) as he almost runs her down with his convertible in the streets of Earl’s Court. Only minutes earlier, Peter, on foot, had bumped into Brenda (Rita Tushingham) at the entrance to a newsagent’s, not even pausing to help or apologise after he knocked her bag – and its contents – out of her hands and onto the ground. Brenda has just arrived in London from her home in Liverpool, in search of a ‘prince of princes’ to father her child – and this initial contretemps with Peter will also turn out to be a meet-cute, as the film plays itself out as a very dark take on the disorienting delirium of romance.

Straight on Till Morning is full of clashes and collisions, whether literal (as above) or metaphorical. The film opens with Brenda’s fairy tale voiceover (a tale of a “wondrous magic garden”, a “beautiful castle” and “the most beautiful princess in the world”) contrasting with a pan over the rooftops of the more prosaic Liverpudlian street where she lives with her mother. Indeed, Brenda’s insistence on filtering her reality through the prism of fantasy creates one of the film’s principal tensions.

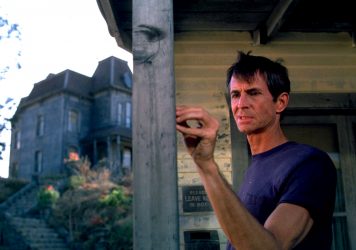

Then there is the clash of northern and southern values, of Brenda’s naïve innocence with the greater worldliness of the Swinging Londoners, and of the youthful idealism of the ’60s with the Manson-esque menace that ushered in the ’70s. This latter spirit is embodied by Peter, who, for all his slippery androgynous charm, is a “bloody maniac” for real – a serial killer of any sexual partners (typically women old enough to be his mother) whom he regards as unloving or, now worse for him, beautiful.

Brenda is very much not Peter’s usual type. She is young and “plain”, even “not pretty at all” – something palpably untrue of Tushingham, but that just has to be accepted within the film’s fictions given how many characters state it as fact. What Peter has in common with Brenda is his fancifulness. For he, like her, has constructed a fantasy around himself. Brenda introduces herself to Peter as “Rosalba” – the name of the princess in the fairy tale that she has been writing. Peter too is traveling under a pseudonym – his real name is Clive – and he tells his own story to Rosalba via the allegory of a fairy tale.

Without knowing that Rosalba’s real name is Brenda, Peter redubs her “Wendy”, both as a controlling measure, and as a reflection of his obsession with the story of Peter Pan (he tells an earlier victim that he is taking her to “Never Never Land”, and his dog’s name, Tinker, comes close to Tinkerbell). Together, this odd couple – the ingenue and the momma’s boy – seek to reinvent themselves, and to transform the world around them into infantilised myth, even as harsher realities close in.

While Peter recalls the mother-loving Norman Bates from Psycho, he is perhaps closer, through his use of recording devices, to Mark Lewis from Peeping Tom. And his affair with Brenda, though apparently doomed from the start, is nonetheless played as a genuine romance which the viewer wills to succeed, despite seeing it for the illusion that it is. Meanwhile director Peter Collinson (The Italian Job, Fright, Open Season) shows these characters’ fragmented grip on reality by having his editor, Alan Pattillo, slice up the film like something from the French New Wave (or perhaps like one of Peter’s victims), with syncopated shots, jump cuts and pronounced discontinuities of both space and time. The result is a heady descent into Brenda and Peter’s individual and collective madness, which also captures the shifts and contradictions of the times.

Look closely at the stained-glass door on Peter’s bijou Mews pad and you will see a bird with crystal plumage, signalling the film’s connection less to Hammer’s characteristic castle horror, and more to the modern psycho thrills of a Dario Argento giallo. For Straight on Till Morning, though a Hammer production, forgoes entirely that label’s usual gothic motifs. Indeed, here the setting is entirely contemporary, while the only castles to be found exist exclusively in Brenda’s mythomaniac imagination. “Children’s stories are cruel,” Brenda will tell Peter – but the monstrous actualities of ’70s Britain will turn out to be crueller.

Straight on Till Morning is released by StudioCanal in a Blu-ray/DVD Doubleplay edition on 29 January 2018.

Published 29 Jan 2018

By Ivan Radford

The director’s deep affection for his home city can be felt throughout his revered body of work.

By Anton Bitel

Richard Franklin’s follow-up to the Hitchcock classic is a chilling horror in its own right.

By James Oddy

Lindsay Anderson’s exhilarating look at the psyche of rugby league player has lost none of its emotional punch.